It’s really vital to drink enough water when you work out to stay hydrated. Knowing how to stay hydrated will help you get more out of your workouts and keep you from experiencing difficulties that can come when you don’t drink enough water, whether you’re a pro athlete or just starting out. This in-depth tutorial gives you five evidence-based techniques to stay hydrated while working out, all of which are founded on the EEAT principles of experience, expertise, authoritativeness, and trustworthiness. There are useful advice, scientific information, answers to common problems, and trustworthy sources that will help you apply these approaches appropriately and with confidence.

Everyone needs to stay hydrated, including athletes. Your body loses water while you work out, largely through breathing, sweating, and other metabolic activities. You might feel weaker, less able to think properly, and less able to handle things if you lose even 1–2% of your body weight. You are more prone to have heat illness, cramps, or strain on your heart if you lose more weight (Casa et al., 2000). Targeted hydration measures assist keep the blood volume high, the body temperature steady, and the muscles performing.

By the end, you’ll have a powerful, science-based hydration toolset that will help you get the most out of your workouts and speed up your recovery.

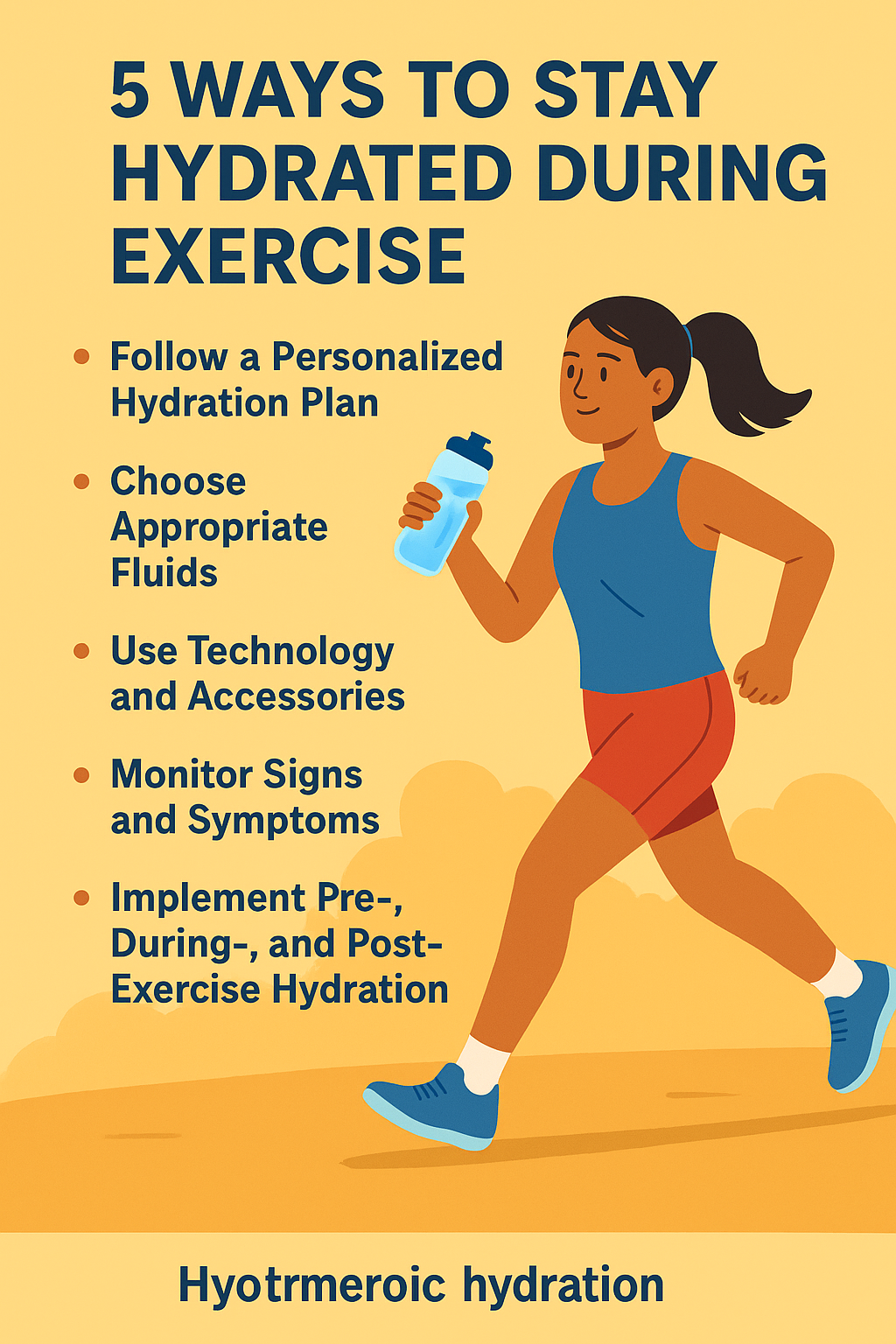

Here are five smart strategies to stay hydrated as you work out:

- Make sure you have a plan for staying hydrated that works for you.

- Pick the Right Drinks

- Use devices and technology

- Look for signs and symptoms

- Make sure you drink enough water before, during, and after working out.

The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM), the National Athletic Trainers’ Association (NATA), and the Mayo Clinic are just a few of the best groups that back each part. We also discuss about how hydration works at the cellular level, common mistakes individuals make, and useful recommendations for making these approaches part of your daily life.

How working out and drinking water change the body

Water is a big part of your body, making up roughly 60% of your weight. It is vital for practically all of your body’s processes (Popkin et al., 2010). When you work out, your body’s core temperature goes up. When you sweat, you lose water and minerals, which makes you cooler. Things you need to know:

- What Sweat Is Made Of: Sweat is primarily water, but it also has minor amounts of salt, potassium, and chloride. If you don’t replace the sodium you lose, you could have muscle cramps or hyponatremia (Mayo Clinic, 2021).

- Blood Volume: If you don’t drink enough water, your plasma volume will drop. When you complete a specific amount of work, this causes your heart work harder and your heart rate go up (Sawka et al., 2007).

- Heat Absorption: Water has a high specific heat, which means it can absorb heat from metabolism. It is harder for the body to remove heat when it has less fluid. This makes the core temperature rise and increases the risk of becoming wounded in the heat.

- Effects on Performance: Even losing 2% of your body weight can make you less able to do tasks (Cheuvront & Kenefick, 2014).

Once you know how these things work, it’s easy to see why focused hydration techniques are so vital for safe and productive activity.

1. Stick to a hydration regimen that works for you.

Some solutions don’t work for everyone because people sweat at various rates, have different body shapes, work out at different levels of intensity, and live in different regions. The greatest plan is one that is developed particularly for you.

1.1. Check how much you sweat

- Weigh In and Out: Before and after a normal workout, weigh yourself with little or no clothes on.

- Learn what you lost: javaCopyEdit

Sweat Rate (L/h) = Weight before exercise − Weight after exercise + Fluid consumed (L) How long you worked out (h) Time spent working out (h) equals Sweat Rate (L/h) Weight before exercise minus weight after exercise plus the amount of fluid drunk (L) - To make up for 80–100% of the perspiration you lose while working out, change how much you eat (Casa et al., 2000).

1.2. Think about the things around you

- You sweat more in hot, humid locations, yet you might not feel as thirsty in cold, dry places.

- Breathing and going to the bathroom are easier at higher elevations, which can make you lose fluids faster (Montain & Coyle, 1992).

1.3. Pre‑workout hydration

- Consume adequate water: The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) suggests you should drink 5–10 mL/kg of body weight at least four hours before you do anything.

- During exercise: Depending on how much you sweat, you should drink between 0.4 and 0.8 liters of water per hour while you work out.

- Post‑exercise: Drink 150% of the fluids you lost in the first two hours (15–25 mL/kg) after working out to make up for the fluids you are still losing.

2. Pick the Right Fluids

Different liquids hydrate in different ways. Electrolytes, carbs, and osmolality all affect how well things are absorbed and how well they work.

2.1. Water or drinks for sports

- For exercises that aren’t too demanding and last less than an hour in cool settings, water is best.

- Sports drinks are helpful for workouts that take more than an hour or are really hard since they offer 6–8% carbs and 300–700 mg/L of salt, which helps with endurance and keeping your electrolytes in balance (Jeukendrup & Gleeson, 2010).

2.2. Choices with a lot of electrolytes

- Coconut water has both potassium and magnesium in it. If you sweat a lot, you might need to take extra supplements because it includes less sodium.

- Mixing water with sea salt (1/4 tsp per liter), honey, and citrus juice can form your own sports drink.

2.3. Recent events

- Waters with extra protein: These fluids have branched-chain amino acids in them, which can help you heal. There isn’t much proof that they aid with short-term hydration (Res et al., 2016).

- Some drinks contain optical hydration sensors that can tell how much fluid is absorbed using patches that can be worn. This is a new form of tech.

3. Use tools and technologies

Using tools can help you remember to drink enough water and keep track of it.

3.1. Smart water bottles

Smart water bottles, such as HidrateSpark and Thermos, remind you to drink, keep track of how much you drink, and keep the temperature.

Pros: It makes you drink more and keeps you drinking.

3.2. Sweat patches for wearable hydration monitors

These patches let you know how hydrated you are right now and how many electrolytes you lose (Garnier et al., 2015). Some smartwatches will remind you to drink water depending on how active you are.

3.3. Hydration packs and belts

Hydration packs and belts are wonderful for runners, cyclists, and hikers since they let you drink without having to hold anything. You may put together several sizes of hydration reservoirs (1–3 L) with compartments for snacks and gear.

3.4. Mobile Apps Tracking

Apps like MyFitnessPal and WaterMinder can help you create goals, keep track of your progress, and remind you to do things.

Integration: Works with wearables to alter goals in real time depending on activity data.

4. Look for signs and symptoms

You still need to keep an eye on yourself, even if you have the best strategies to recognize early indicators of dehydration or overhydration.

4.1. The hue and Amount of Urine Scale of Color

A pale straw to light lemonade hue implies you are well-hydrated, whereas a deeper color means you need more fluids (Armstrong et al., 1994).

4.2. Changes in Weight

Check your weight every day, especially before and after workouts, to discover whether you have any fluid imbalances.

4.3. Signs of Good Health

- Thirst: Not a good indicator; don’t merely drink when you’re thirsty while working out.

- Heart Rate: If your heart rate is higher than normal when you conduct everyday things, you may be dehydrated.

- Heat Cramps: You should consume water and electrolytes immediately away if you feel too hot or have heat cramps.

- Cognitive Performance: If you develop a headache, feel confused, or are dizzy, you should consult a doctor straight soon.

5. Make sure you drink enough water before, during, and after your workout.

You can start exercising in the best way and recover effectively if you break up your hydration into phases.

5.1. Pre‑exercise

- Drink 5 to 10 mL/kg at least four hours before you work out (ACSM, 2007).

- Check the color of your pee. Before you start, attempt to make it light.

- ElectAWAY: If you sweat a lot, take an electrolyte tablet or drink a tiny sports drink.

5.2. During exercise

- Try to drink 150 to 300 mL every 10 to 20 minutes.

- Carbohydrate Intake: If your workouts continue more than 90 minutes, you should eat 30 to 60 grams of carbs every hour (ACSM, 2007).

- Change the speed according on the weather: go faster when it’s hot and humid, and slower if your stomach hurts.

5.3. Post‑exercise

- Drink 1.25–1.5 L for every kilogram of body weight you lose (Sawka et al., 2007).

- Drink sports drinks or eat salty foods to gain additional sodium (20–30 mmol/L).

- Nutrition: Within 45 minutes, drink water and have a snack or meal with 3:1 or 4:1 carbs to protein (Ivy, 2001).

Questions that people often ask:

Q1: How much water should I drink before I work out?

Before you start, you should drink 5 to 10 mL for every kilogram of body weight. This means 350 to 700 mL for a person who weighs 70 kg (ACSM, 2007).

Q2: Can I use my thirst to help me drink enough water while I work out?

You need to drink extra water when you’re thirsty, but that’s not the first indicator. It’s better to drink a certain amount of water, like 150 to 300 mL every 10 to 20 minutes, and then alter it based on how much you sweat.

Q3: What are the risks of drinking too much water?

When the salt level in the blood goes too low, this is called exercise-associated hyponatremia (EAH). This can happen when you drink too many hypotonic beverages. Some of the symptoms are nausea, headaches, and in really bad cases, seizures (Noakes et al., 2005).

Q4: Do you have to take sports drinks before every workout?

No. If your sessions are less than an hour long and not too hard, plain water is all you need. If you work out for more than an hour, especially if it’s hot outside, sports drinks can help.

Q5: Is it possible to drink meals to stay hydrated?

Yes. Watermelon, oranges, and cucumbers are all fruits that are largely made of water. They also offer carbs and electrolytes that help you stay hydrated.

Q6: How can I know if I’ve had too much to drink?

Watch out for nausea, bloating, clear urine that comes out in huge amounts, and weight gain that happens quickly. Eat less if these things happen.

Q7: Does caffeine make you sweat more while you exercise?

Drinking moderate levels of caffeine (<300 mg) doesn’t have much of an effect on diuresis, so you can add it to your pre-workout drinks without worrying about getting dehydrated (Maughan & Griffin, 2003).

Q8: Should I weigh myself every day to find out how much water I drink?

Yes, weighing yourself every morning under the same settings might help you detect patterns in how much water you have, but don’t get too fixated. You should also worry about other factors, such what you have in your stomach and glycogen.

The end

Drinking as much as you can while working out isn’t the best approach to remain hydrated. You should instead arrange when and how much water and electrolytes you drink based on your particular needs, the weather, and the kind of exercise you’re performing. You may improve your health, performance, and recovery by following a specific hydration strategy, choosing the proper fluids, employing technology, paying attention to your body’s signals, and arranging your hydration phases before, during, and after exercise. Don’t forget to use these techniques during training, look up the actual guidelines, and adjust them based on what you learn in real life.

References

- Casa, D. J., et al. (2000). National Athletic Trainers’ Association Position Statement: Fluid Replacement for Athletes. Journal of Athletic Training. https://www.nata.org/sites/default/files/fluid_replacement.pdf

- Popkin, B. M., et al. (2010). Water, hydration, and health. Nutrition Reviews, 68(8), 439–458. https://academic.oup.com/nutritionreviews/article/68/8/439/1939402

- Mayo Clinic. (2021). Exercise-induced hyponatremia: Symptoms and treatment. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/exercise-hyponatremia/symptoms-causes/syc-20354070

- American College of Sports Medicine. (2007). ACSM Position Stand: Exercise and Fluid Replacement. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 39(2), 377–390. https://journals.lww.com/acsm-msse/Fulltext/2007/02000/ACSM_Position_Stand__Exercise_and_Fluid.27.aspx

- Cheuvront, S. N., & Kenefick, R. W. (2014). Dehydration: Physiology, assessment, and performance effects. Comprehensive Physiology, 4(1), 257–285. https://physiologyonline.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1002/cphy.c130017

- Montain, S. J., & Coyle, E. F. (1992). Influence of graded dehydration on hyperthermia and cardiovascular drift during exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology, 73(4), 1340–1350. https://journals.physiology.org/doi/abs/10.1152/jappl.1992.73.4.1340

- Jeukendrup, A., & Gleeson, M. (2010). Sport Nutrition: An Introduction to Energy Production and Performance. Human Kinetics.