As we get older, our internal clock (circadian rhythm) and sleep drive change in predictable ways. Many people notice earlier bedtimes and wake-ups, lighter sleep, more awakenings, and the urge to nap. In short: aging and circadian rhythms interact so that sleep becomes earlier and more fragmented, while deep sleep shrinks and environmental timing (light, meals, meds) matters more. This article explains what’s happening and—crucially—how to adapt your routine to sleep better.

Quick definition: Circadian rhythms are 24-hour biological cycles that time sleep and alertness; with aging, the clock tends to advance (earlier schedule) and the homeostatic “sleep pressure” weakens, producing lighter, more broken sleep. Evidence-based fixes include targeted evening light, consistent schedules, smart nap limits, and cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I).

Medical note: This guide is educational, not a substitute for personal medical care—especially if you snore loudly, stop breathing during sleep, have leg discomfort at night, act out dreams, or take multiple medications. Consult a clinician or sleep specialist.

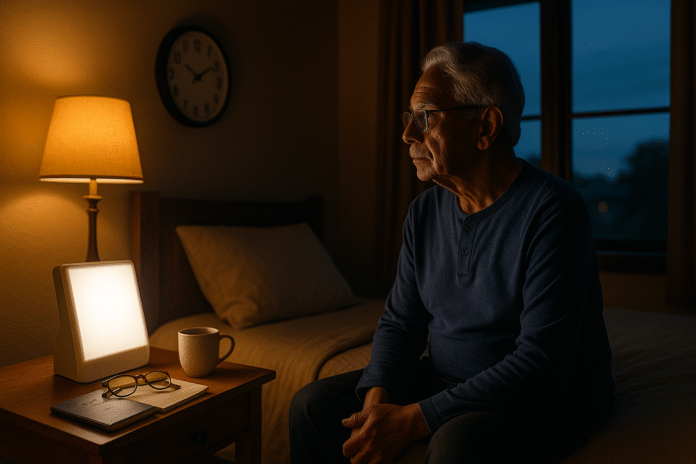

1. Your body clock shifts earlier (advanced sleep phase)

Older adults commonly feel sleepy earlier in the evening and wake up earlier in the morning because the circadian clock advances with age. This shift can be a blessing if your lifestyle fits it, but it creates problems when family, social events, or obligations require later evenings. The earlier clock combines with lighter sleep to produce 3–5 a.m. wakeups. Fortunately, the clock is adjustable. Timed evening bright light can delay the internal rhythm, push bedtime later, and reduce predawn awakenings; consistent wake-up times and strategic dimming of light late at night strengthen the reset. If you’re already turning in around 8–9 p.m. and waking at 4 a.m., this section is for you.

Why it matters

A phase-advanced clock can fragment sleep, limit social life, and cause misalignment (“social jet lag”) with others on later schedules. It also shortens the late-night window for REM sleep.

How to do it

- Evening light therapy (7–9 p.m.). Use a 2,000–2,500-lux lightbox at eye level for ~30–60 minutes to delay your clock. Do not use near bedtime.

- Dim late-night light. After the lightbox session, keep lighting low and warm until bedtime.

- Anchor your wake-up. Set a steady wake time daily (even weekends).

- Get daylight after your desired wake time. Morning sun reinforces day–night contrast; avoid very early morning bright light while shifting later.

- Shift gradually. Move bedtime/wake time by 15–30 minutes every few days.

Numbers & guardrails

Clinical guidance supports evening light for advanced sleep-wake phase disorder; discuss with your clinician if you have retinal disease, bipolar disorder, or migraines. Sleep Education

Bottom line: Use evening bright light and consistent timing to nudge your clock later and reduce those 3–5 a.m. wakeups.

2. Melatonin patterns and light sensitivity change with age

Melatonin, the “darkness signal,” often shows a lower nighttime peak or altered timing in older adults. At the same time, the eye’s lens yellows and pupils become smaller, filtering out blue-teal wavelengths that most strongly set the clock. Less blue light by day plus more artificial light at night flattens the day–night contrast your brain needs, weakening circadian signals. Some people consider melatonin supplements; while low doses can help in specific cases, timing and dosing matter and should be discussed with a clinician—especially alongside other meds.

Why it matters

Weaker melatonin signals and reduced daytime light exposure can produce lighter, more fragmented sleep and earlier wake times. Cataracts further reduce blue-light transmission; interestingly, cataract surgery may improve circadian light input in some patients. PMC

How to do it

- Boost daytime light. Aim for at least 30–60 minutes of outdoor light most days; keep indoor spaces bright by day.

- Dim evening light. Two hours pre-bed, switch to low, warm lighting; minimize bright screens.

- Melatonin, if used: Many older adults respond to very low doses (e.g., 0.3–1 mg) taken 1–3 hours before the intended bedtime; higher doses can cause next-day grogginess. Coordinate with your clinician.

Numbers & guardrails

Research shows nocturnal melatonin peaks often decline with age (though not universally). Clinical guidelines also support melatonin for select circadian rhythm disorders, with careful timing. Oxford AcademicScienceDirect

Bottom line: Strengthen the light–dark contrast and consider low-dose, well-timed melatonin only with clinician input.

3. Sleep gets lighter and more fragmented

With age, total sleep time and sleep efficiency (time asleep divided by time in bed) tend to decline. Deep slow-wave sleep (SWS) shrinks; light N1 sleep expands. The result is a night punctuated by brief awakenings, noise sensitivity, and “I’m awake again” moments. This is normal aging—but you’re not helpless. Building stronger sleep pressure by day, optimizing the room, and pacing fluids and meds can improve continuity. Addressing medical contributors (pain, nocturia, reflux) is equally important.

Common contributors

- Nocturia: Fluids, evening salt, edema, and diuretic timing push nighttime bathroom trips.

- Pain and comorbidities: Arthritis, neuropathy, reflux, cough, and breathing issues all interrupt sleep.

- Environment: Light leaks, heat, noise, and pets keep you in lighter stages.

Mini-checklist

- Evening fluids: Taper 2–3 hours before bed; limit evening alcohol/caffeine; elevate legs for edema.

- Room climate: Keep it cool (about 60–67°F / 15–19°C), dark, and quiet; consider white noise.

- Pain plan: Time non-sedating pain relief earlier in the evening if appropriate; discuss options with your clinician.

- Sleep window: Keep a consistent 7–8 hour window; don’t extend time in bed to “chase” sleep.

Bottom line: Expect some fragmentation with age, but optimize fluids, climate, and routines to protect continuity.

4. Deep sleep (slow-wave) declines—so build sleep pressure

Deep slow-wave sleep naturally diminishes from midlife onward, especially in men. Because SWS is restorative and stabilizes sleep, its loss makes awakenings more likely. You can’t “force” deep sleep, but you can build sleep pressure: be active by day, get light exposure, keep your sleep window realistic, and avoid long late naps. Gentle resistance exercises and daytime walks are especially helpful for sleep quality and strength. JAMA Network

How to do it

- Daytime activity: Aim for regular movement and light strength work most days (after medical clearance).

- Right-sized sleep window: 7–8 hours in bed for most older adults is realistic.

- Evening unwind: Use a predictable wind-down (reading, relaxation breathing) to smooth the transition.

Numbers & guardrails

On population averages, older adults typically need 7–8 hours nightly; don’t extend time in bed far beyond that or you risk more light, broken sleep.

Bottom line: You can’t restore youthful SWS, but you can raise sleep pressure and protect the deep sleep you have.

5. Social schedules can collide with an earlier chronotype

Even if your body wants 9:30 p.m.–5:30 a.m., life may not cooperate. Late dinners, evening events, or family routines can cause “social jet lag”—a mismatch between your internal clock and your schedule that worsens insomnia. The fix is twofold: set anchor times and use zeitgebers (time-givers) like light, meals, and activity to keep your clock steady. Small, consistent changes beat big swings. Sleep Foundation

Tools/Examples

- Anchor wake-up: Pick one wake time and defend it daily.

- Meal timing: Keep dinner 3+ hours before bed; avoid heavy, late meals.

- Activity timing: Put stimulating tasks earlier; relaxing tasks after 7 p.m.

- Light timing: Evening bright light if you’re trying to shift later; dim home lighting after the session.

Mini case

A 72-year-old who woke at 4:30 a.m. shifted to 5:45 a.m. within two weeks by using a 2,500-lux lightbox 8:15–8:45 p.m., dimming lights thereafter, anchoring wake at 5:45, and keeping dinner before 7 p.m. (Individual results vary.)

Bottom line: Protect your anchor times and use light/behavioral cues to reduce social jet lag.

6. Naps help—if you cap them and time them right

Daytime sleepiness often increases with age due to lighter night sleep and medical conditions. Naps can restore alertness, mood, and memory—but long or late naps can steal from nighttime sleep. For most, a 10–30 minute “power nap” before 3 p.m. boosts energy with minimal grogginess. If you’re severely sleep-deprived, an occasional ~90-minute full-cycle nap earlier in the afternoon can help—but avoid making it a habit if it worsens night sleep.

Why it matters

Short naps improve vigilance and cognition; very long or late naps can increase sleep inertia and fragment nighttime sleep. Older adults nap more often—so structure matters. PMC

Nap checklist

- Set a timer for 10–30 minutes; nap in a quiet, cool, dim space.

- Aim early afternoon (roughly 1–3 p.m.); avoid after 3 p.m.

- Try a “nappuccino”: sip coffee right before a 20-minute nap for an easier wake-up (if you tolerate caffeine).

- Track impact: If night sleep worsens, shorten or skip naps.

Bottom line: Short, early naps can help; long or late naps often backfire on nighttime sleep.

7. Hidden sleep disorders are more common with age (OSA, RLS/PLMD, RBD)

Three culprits frequently undermine older adults’ sleep: obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), restless legs syndrome (RLS)/periodic limb movements (PLMD), and REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD). OSA prevalence rises with age and body weight; RLS may affect a meaningful minority of older adults; RBD—acting out dreams—though rarer, carries neurological implications and warrants prompt evaluation. If you snore loudly, stop breathing at night, feel an irresistible urge to move your legs in the evening, or physically enact dreams, seek assessment. Journal of Global HealthCleveland Clinic

Signs & screening

- OSA: Snoring, witnessed apneas, morning headaches, daytime sleepiness. STOP-Bang is a simple screener your clinician may use.

- RLS/PLMD: Evening leg discomfort relieved by movement; sleep fragmentation. PubMed

- RBD: Punching/kicking during dreams; strong link with alpha-synuclein disorders—neurology referral is typical.

What helps

- OSA: Weight management, positional therapy, oral appliances, and CPAP; treatment improves daytime function and cardiovascular risk.

- RLS: Check ferritin/iron; review meds that worsen symptoms; consider targeted therapies.

- RBD: Environmental safety (padded surroundings), melatonin or clonazepam per specialist. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine

Bottom line: Screen and treat common sleep disorders; they’re frequent in later life and very treatable. PubMed

8. Medications and comorbidities can sabotage sleep

Polypharmacy is common in older adults, and many drugs disturb sleep timing or architecture—think certain antidepressants, decongestants, corticosteroids, diuretics (nocturia), and beta-blockers (melatonin suppression in some). Sedative-hypnotics (benzodiazepines and “Z-drugs”) may increase falls, confusion, and next-day impairment; major guidelines advise avoiding them for chronic insomnia in older adults. Safer, first-line care is CBT-I; when medication is considered, shared decision-making and fall-risk mitigation are essential. PMC

Practical steps

- Medication review: Ask your clinician to review all meds for sleep effects; adjust diuretic timing earlier in the day if possible.

- Insomnia care: Prioritize CBT-I (4–8 sessions, in-person or digital). AASM

- Caution with sedatives: Beers Criteria lists benzodiazepines and several hypnotics as potentially inappropriate for older adults due to fall/cognitive risks.

Numbers & guardrails

AASM clinical guidelines support CBT-I as first-line for chronic insomnia; pharmacologic options, when used, require caution in older adults. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine

Bottom line: Review meds, prefer CBT-I, and be sedative-smart to protect sleep and safety.

9. Your bedroom and routine should amplify your clock—not fight it

Small environmental tweaks pay big dividends. Keep the room cool, dark, and quiet; minimize trip hazards for nighttime bathroom visits; and craft a predictable wind-down that tells your brain it’s time to sleep. Light is the strongest signal—bright by day, dim by night. A simple sleep diary for two weeks can surface patterns to fix (late naps, late dinners, bright lights). Pair these with a consistent schedule, targeted light timing (Section 1), and a calm pre-bed routine.

Mini-checklist

- Temperature: 60–67°F (15–19°C) works for most; adjust bedding/clothing, not just the thermostat.

- Light: Daylight exposure daily; warm, low light at night; block light leaks (curtains, masks).

- Noise: White-noise device or fan; relocate ticking clocks.

- Safety: Night-lights to the bathroom, clear cords/rugs, stable footwear.

- Wind-down (20–40 min): Gentle stretches, reading, relaxation breathing (e.g., 4-6 breathing), or a brief body scan.

Tools/Examples

- Light boxes (2,000–2,500 lux for evening delay), white-noise apps, simple sleep diaries, and CBT-I programs (clinic or digital) all support better nights.

Bottom line: Shape your environment and habits to amplify circadian cues and protect sleep continuity.

FAQs

1) How much sleep do older adults need?

Most healthy adults 65+ do well with 7–8 hours per night. Some individuals feel fine with a bit less or more, but routinely sleeping far under 6–6.5 hours or needing 9+ could signal a problem. Focus on how you feel in the daytime—energy, mood, and attention—as well as safety (no drowsy driving).

2) Is melatonin safe for seniors? What dose?

Melatonin can be helpful for specific issues (like circadian timing), but product quality varies and interactions exist. Many older adults respond to low doses (0.3–1 mg) taken 1–3 hours before the desired bedtime. Higher doses can cause next-day grogginess or interact with other meds. Discuss with your clinician before starting.

3) What’s the best time for light therapy if I wake up too early?

For an earlier-than-desired schedule, use evening bright light (around 7–9 p.m.) to delay your clock. Keep home lighting dim afterward and maintain a consistent wake time. Morning bright light is used to advance clocks, which would make you even earlier.

4) Are naps bad for older adults?

Short, early-afternoon naps (10–30 minutes) can improve alertness and mood without hurting nighttime sleep. Long or late naps (especially after 3 p.m.) often worsen insomnia. If you’re very sleep-deprived, a rare ~90-minute early nap can help—evaluate whether it harms your night. Sleep FoundationMayo Clinic

5) I wake to urinate several times. What can I change?

Try tapering fluids 2–3 hours before bed, minimizing evening alcohol/caffeine, elevating your legs in the evening if you have ankle swelling, and asking your clinician about adjusting diuretic timing. Screening for sleep apnea is also worthwhile, as it can contribute to nocturia.

6) I’ve taken sleeping pills for years. Should I stop?

Don’t stop abruptly. Talk with your prescriber about a gradual taper and switching to CBT-I, which is first-line for chronic insomnia. Many sedatives raise fall and confusion risk in older adults; shared decision-making can reduce harm while maintaining sleep. AASM

7) How do I know if I have sleep apnea?

Typical clues are loud snoring, witnessed pauses, gasping/choking at night, morning headaches, and daytime sleepiness. Your clinician may use the STOP-Bang screener and order a home sleep test or polysomnography. Treatment (e.g., CPAP) can dramatically improve quality of life.

8) What bedroom temperature is best?

Most people sleep best around 60–67°F (15–19°C), with a cool, dark, quiet room. Adjust bedding and pajamas to fine-tune comfort without overheating. Cleveland Clinic

9) Is CBT-I really better than sleep medication?

For chronic insomnia, yes—multiple guidelines recommend CBT-I as the first-line therapy because it improves sleep and maintains gains without medication risks. It typically involves 4–8 sessions (in person or digital).

10) Can cataract surgery change sleep?

Some research suggests restoring blue-light transmission after cataract surgery may improve circadian signaling and sleep in certain individuals, though results vary. If you notice sleep changes post-surgery, share them with your ophthalmologist and primary clinician. JAMA Network

Conclusion

Aging changes both how we sleep and when we sleep. The circadian clock shifts earlier; sleep becomes lighter and more easily disrupted; and medical issues, medications, and environment play larger roles. The good news: you can take control. Strengthen your light–dark cycle, set consistent anchor times, cap and time naps, manage evening fluids, and prioritize CBT-I over sedatives. Screen for common sleep disorders like OSA, RLS/PLMD, and RBD. Small, strategic adjustments—especially evening light therapy for an advanced clock and a cooler, darker bedroom—add up quickly. Start with one or two changes from this list, track your results for two weeks, and iterate with your clinician.

Ready to act? Pick an anchor wake time, schedule a nightly wind-down, and set up evening light therapy—then keep going.

References

- Sleep in Normal Aging, National Library of Medicine (PMC), 2017. PMC

- How Much Sleep Do We Really Need?, National Sleep Foundation, 2015 / updated 2020–2025. ; PubMedNational Sleep Foundation

- Behavioral and Psychological Treatments for Chronic Insomnia Disorder in Adults: An AASM Clinical Practice Guideline, Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 2021. PMC

- Advanced Sleep-Wake Phase, SleepEducation (AASM patient resource), 2021. Sleep Education

- Advanced Sleep Phase Disorder, Sleep Foundation, 2024. Sleep Foundation

- Kessel L. et al., Sleep Disturbances Are Related to Decreased Transmission of Blue Light to the Retina Caused by Lens Yellowing, Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 2011. PMC

- Turner P. & Mainster M., Circadian Photoreception: Ageing and the Eye’s Important Role in Systemic Health, British Journal of Ophthalmology, 2008. bjo.bmj.com

- Auger R. et al., Treatment of Intrinsic Circadian Rhythm Sleep-Wake Disorders, AASM Practice Guideline, 2015. AASM

- Zhdanova I. et al., Melatonin Treatment for Age-Related Insomnia, J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2001. PubMed

- The Best Temperature for Sleep, Sleep Foundation, 2025. Sleep Foundation

- Pivetta B. et al., Use and Performance of the STOP-Bang Questionnaire for OSA Across Geographic Regions, JAMA Network Open, 2021. JAMA Network

- Nocturia: Lifestyle and Clinical Management, Nature Reviews Urology / NIH resources, 2020–2024. ; PMCSleep Foundation

- Barone D. & Henchcliffe C., REM Sleep Behavior Disorder and the Prodromal Synucleinopathies, 2018. PMC

- 2023 AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults, American Geriatrics Society, 2023. sbgg.org.br