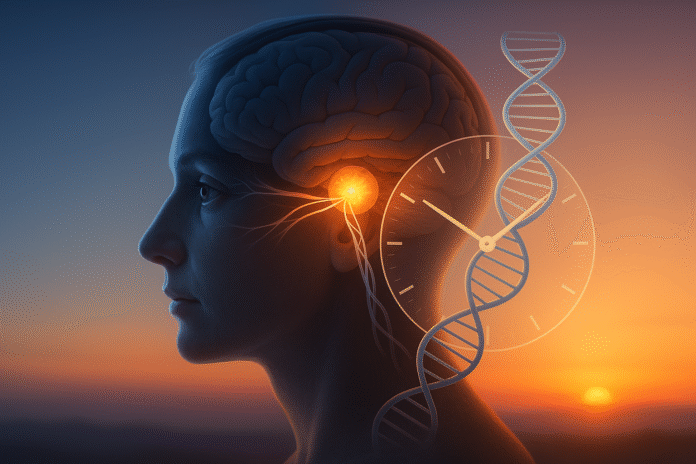

Your sleep schedule isn’t just about willpower or coffee—it’s anchored by circadian genes, the DNA instructions that build your internal 24-hour clock. These genes set your natural bedtime and wake time (your chronotype), determine how sensitive you are to light, and help synchronize clocks across your brain and body. In one line: circadian genes create the molecular rhythm that predicts when you feel sleepy and alert; daily cues like light, meals, activity, and social timing then tune that rhythm. This guide explains the nine gene pathways most relevant to real-world sleep timing—plus concrete steps to work with, not against, your biology.

Quick note: This article is educational and not medical advice. If you suspect a sleep disorder, consult a qualified clinician.

1. CLOCK & BMAL1: The “starter pistol” that sets your daily rhythm

CLOCK and BMAL1 are the activator pair that kick off each daily cycle of your internal clock. In plain terms, they bind together and turn on other core clock genes (notably PER and CRY), starting a feedback loop that takes ~24 hours to complete. That loop runs in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN)—the master pacemaker in your brain—and in nearly every organ, creating thousands of daily gene-expression cycles tied to sleep–wake timing, metabolism, temperature, and hormones. When this activator pair is mistimed or disrupted (by shift work, irregular light, or rare variants), the whole schedule drifts, making consistent sleep harder. While true loss-of-function mutations are rare, the CLOCK:BMAL1 system is what your daily habits “talk to,” which is why light, meals, and activity can meaningfully shift your schedule. In short: this duo sets the day, and your lifestyle cues confirm it.

How to work with it

- Anchor a wake time within a 30-minute window daily; the CLOCK:BMAL1 loop stabilizes when your first light and movement are predictable.

- Get outdoor light within 30–60 minutes of waking (5–30 minutes depending on cloud cover) to strengthen the SCN signal.

- Front-load activity and calories toward the first 2/3 of your biological day; late heavy meals can feed back and blur the loop.

1.1 Why it matters

When CLOCK:BMAL1 fires on time, downstream rhythms (melatonin onset, body temperature minimum) line up, making sleep pressure and alertness predictable. Misalignment pushes those landmarks later or earlier, which you experience as “wired at night” or “dragging all morning.”

Bottom line: act on this pair with consistent wake-time light and routine; it’s the most powerful lever most people control daily.

2. PER & CRY: The “brakes” that decide how early or late you run

If CLOCK:BMAL1 starts the loop, PER (PER1/2/3) and CRY (CRY1/2) close it. As PER and CRY proteins build up through the day, they shut down the activator pair, pausing transcription until levels fall and a new cycle can start. Small changes in these genes can change your intrinsic period (how long one cycle takes) and your sensitivity to light—both key to whether you trend early-bird or night-owl. A well-studied human example is a CRY1 splice variant (Δ11) that lengthens the molecular day and is associated with delayed sleep–wake phase disorder (DSWPD): people naturally fall asleep and wake up much later than social schedules allow. Variants in PER2 can have the opposite effect (see Section 3). Because PER/CRY set the “stop time” on each cycle, they’re where late-night light and late socializing often do the most damage—pushing the brakes later, one evening at a time.

Mini-checklist to counter a “late” PER/CRY bias

- Strict dimming after sunset: keep indoor light ≤30–50 lux in the last 2–3 hours before bed; use warm lamps, task lighting, and screen filters.

- Time melatonin cautiously: low doses (0.3–1 mg) taken ~4–6 hours before habitual sleep can advance timing; larger doses are not more effective for shifting and may grog you.

- Create “social cutoffs”: set recurring alarms to stop stimulating tasks and light at a defined hour.

2.1 Numbers & guardrails

People with bona fide DSWPD often show sleep onset and offset delayed by 1–3+ hours relative to local norms. Advancing the clock typically requires days to weeks of consistent morning light + evening dim + correctly timed melatonin; skipping even a couple of nights can re-delay the cycle.

Takeaway: If you skew late, treat PER/CRY like sensitive brakes—protect evenings from bright light and caffeine to let them engage on time.

3. PER2 & CK1δ (CSNK1D): Why some families are “extreme morning larks”

Some families carry rare variants that shift the clock much earlier, known as Familial Advanced Sleep Phase Syndrome (FASPS). Two classic culprits are a phosphorylation‐site change in PER2 (S662G) and a kinase change CK1δ (T44A) in CSNK1D, the enzyme that tags PER proteins to keep time. These tweaks speed up when the brakes engage, advancing sleep, temperature, and melatonin rhythms by hours. Clinically, affected people feel sleepy in the early evening and wake well before dawn—great for sunrise hikes, rough for evening social life. Recognizing a FASPS-like pattern matters because treatment aims not to “force early bedtime,” but to hold the clock later with evening light and careful melatonin timing.

Practical protocol for early-shifted clocks

- Evening bright light (1,000–2,500 lux for 1–2 hours) between ~19:00–22:00 can delay the clock; avoid bright morning light on off-days.

- Melatonin later (small dose, ~0.3–1 mg) near bedtime may help consolidate sleep without advancing further.

- Social cues matter: schedule workouts and larger meals later in the day to reinforce a later phase.

3.1 Case example

A parent and adult child both sleepy at 19:30 and up at 03:30 most of their lives likely show a familial pattern. Shifting both by ~60–90 minutes may take 2–3 weeks of evening light and morning light avoidance, then maintenance.

Bottom line: If your body is pathologically “early,” evening light is medicine; lean into it strategically.

4. PER3 VNTR: The gene that shapes your tolerance to sleep loss

Unlike the rare PER2/CK1δ changes, a common length variant in PER3 (a variable number tandem repeat, or VNTR) influences how your brain handles sleep pressure and cognitive performance after short nights. People with the PER3-long genotype often show stronger sleep homeostasis: they get deeper early-night sleep and suffer more when they miss it (worse attention and mood after deprivation). PER3-short carriers tend to tolerate short nights a bit better—but can drift later and accumulate sleep debt quietly. This is not destiny; it’s a vulnerability profile that tells you how tightly you should protect your first sleep cycle and how risky late nights are for you.

If you’re likely PER3-sensitive, protect your first 90 minutes

- Block late light and heavy problem-solving after 21:00–22:00 to preserve early slow-wave sleep.

- Stack high-focus work in your first 3–5 daytime hours, when recovery is strongest.

- Cap “social jet lag” (weekend bedtime/wake difference) to ≤1 hour; bigger swings hit performance harder on Monday.

4.1 Tools/Examples

Wearables that report deep sleep minutes, morning reaction-time tests, and weekly mood logs help you spot PER3-like sensitivity: big dips after one late night are a hint to tighten evening hygiene.

Synthesis: PER3 doesn’t pick your bedtime; it tells you how expensive it is to break it.

5. OPN4 (Melanopsin) & ipRGCs: Your “light sensor” gene that sets phase from the eyes

Light is the master cue, and melanopsin (OPN4) inside intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs) is the pigment that tells your brain “it’s daytime.” Variants and expression differences in this pathway modulate how strongly your SCN responds to light—why some people are exquisitely sensitive to evening screens and others less so. Blue-enriched light (∼480 nm) hits melanopsin hardest; even modest indoor lighting late at night can delay your melatonin onset if your OPN4/ipRGC system is responsive. Conversely, strong morning light rapidly advances your clock. Understanding this pathway reframes “sleep hygiene”: it’s not just brightness, it’s timing + spectrum + duration against your biology.

Light-timing playbook

- Morning: 5–30 minutes of outdoor light soon after wake (longer if overcast).

- Daytime: keep workspaces bright; aim for window or outdoor breaks.

- Evening: shift to warm, dim light; consider 2–3-hour “screen sunset” or blue-shifted devices.

5.1 Region-specific note

If you live where Daylight Saving Time shifts evening light later (not currently observed in Pakistan), build an earlier indoor “light curfew” in spring. Close blinds and rely on warm task lights to avoid passive delays.

Takeaway: If you’re “light sensitive,” treat OPN4 like a volume knob—turn mornings up and evenings way down.

6. REV-ERB (NR1D1) & ROR: The stabilizers linking clock, mood, and metabolism

REV-ERBα/β (NR1D1/2) and RORs form a secondary loop that fine-tunes BMAL1 levels and propagates timing into metabolic and immune genes. Think of them as stabilizers that smooth the clock and connect it to energy use, inflammation, and even mood circuits. Variants in NR1D1 have been associated with chronotype in some cohorts, and animal work shows REV-ERB signaling affects dopamine and serotonin pathways relevant to mood. These pathways also gate drug metabolism and may influence when medications work best (chronopharmacology). For sleepers, the headline is practical: when stabilizers are in sync, you get steadier energy across the day and cleaner sleep pressure at night.

How to support the stabilizers

- Regular meal timing: align your largest meals with your biological daytime; late-night eating can desynchronize REV-ERB-linked liver clocks.

- Daily activity window: anchor exercise in the same 6–10-hour block each day; consistency beats perfection for clock stability.

- Caution with naps: if you’re evening-skewed, keep them short (<20–30 minutes) and early.

6.1 Numbers & guardrails

As of August 2025, over 300 medications show time-of-day differences in efficacy/tolerability in research contexts. If you’re on chronic meds that affect alertness, ask your clinician whether a morning vs. evening dose trial is reasonable.

Synthesis: REV-ERB/ROR don’t set bedtime, but they decide how smooth the road feels between breakfast and lights-out.

7. CLOCK variants (e.g., rs1801260): Subtle pushes toward eveningness

Common CLOCK polymorphisms, notably rs1801260 (3111T/C), are associated with modest eveningness, slightly later sleep timing, and in some studies later meal timing and higher snack propensity. The effect sizes are small—tens of minutes, not hours—but add up when combined with modern light and social schedules. If you carry evening-leaning CLOCK variants, you may find it unusually easy to drift later over a few nights and hard to return without a deliberate plan. Recognize the pattern and build friction against late drift, rather than relying on catch-up sleep (which rarely fixes timing).

Anti-drift habits

- Weeknight “shutdown routine” at the same clock time: dim lights, close tabs, prep tomorrow, then low-stimulation activities.

- Meal anchors: finish the last caloric meal 3–4 hours before target bedtime most nights.

- Weekend cap: limit bedtime/wake variability to ≤1 hour to avoid Monday “mini-jet-lag.”

7.1 Mini example

Someone with an evening-leaning CLOCK genotype who watches bright-screen TV until 00:30 may push melatonin onset later by 30–90 minutes across a week; replacing the last hour with low-lux activities can pull it back without touching alarm time.

Takeaway: Small genetic pushes become big schedule shifts under bright-late light. Build evening friction.

8. Protein clocks across your body: SCN vs. peripheral gene rhythms

While the SCN sets the master time, your liver, muscle, fat, and gut each run their own PER/CRY/CLOCK/BMAL1 loops that respond to feeding, activity, and temperature. Mis-timing those cues—late dinners, very late workouts, or sleeping in bright rooms—desynchronizes body clocks from the SCN, fragmenting sleep and energy. The genes here aren’t different; it’s the same clock toolkit deployed in different tissues. You feel peripheral misalignment as “tired but wired”: sleepy at odd times, hungry late, wide-awake at bedtime. The fix is less about genetics testing and more about consistent daily timing that lets the SCN lead and the periphery follow.

Synchrony checklist

- Light: bright mornings, dim evenings (Sections 1, 5).

- Food: set a daily eating window that ends 3–4 hours before bed; keep it stable across weekdays/weekends.

- Movement: regular daytime exercise; avoid strenuous late-night sessions that flood you with alerting signals.

8.1 Why it matters

Even with “neutral” genetics, desynchrony degrades sleep quality. With evening-skew variants, it’s a multiplier. Aligning peripheral cues is how you turn gene knowledge into better nights and sharper days.

Synthesis: One clock leads, many follow—line up light, food, and movement so your genes can keep time together.

9. The polygenic picture: Hundreds of loci nudge your chronotype

No single gene fully decides your sleep schedule. Large genome-wide association studies (GWAS) now link hundreds of loci—across core clock genes, phototransduction pathways, and neuronal signaling—to morningness/eveningness. The heritability of chronotype from these common variants is modest (on the order of ~10–15% in big datasets), which is science’s way of saying genes set your starting bias, and environment does the rest. Rare variants (like CRY1 Δ11 or PER2 S662G) can produce big shifts, but most people inherit small nudges that accumulate with modern light and social timing. For day-to-day decisions, think of genetics as a map, not a destiny.

Putting the polygenic map to work

- Test if helpful: clinical genetic testing is rarely needed; consumer tests can be educational but shouldn’t dictate treatment.

- Experiment systematically: hold wake time constant and adjust light/meal/activity blocks over 2–3 weeks to see how far your clock will flex.

- Escalate when needed: if you suspect DSWPD/FASPS or persistent insomnia, ask for a sleep medicine referral; treatments exist and are effective.

9.1 Tools/Examples

Use a simple phase log: record wake time, first outdoor light, exercise time, last meal, lights-out, and sleep onset. After 2–3 weeks, you’ll know which levers move your clock most.

Takeaway: Your schedule is polygenic—and plastic. Small, consistent changes beat heroic weekend resets.

FAQs

1) What are “circadian genes,” exactly?

They’re genes that build your cellular clock: activators like CLOCK and BMAL1, brakes like PER and CRY, and modulators like REV-ERB/ROR and CK1δ/ε. Together they create a ~24-hour transcriptional loop that times sleep pressure, hormone release, temperature, and alertness. Daily cues—light, meals, activity—sync that loop to the outside world.

2) How much of my sleep schedule is genetic vs. lifestyle?

For most people, genetics explains a modest slice (roughly 10–15% in large studies) of chronotype differences. Rare variants can shift timing by hours, but most of us inherit small nudges that amplify under late light and irregular schedules. Lifestyle still supplies the strongest push for most people.

3) I think I’m a “true night owl.” Can I change?

Usually yes, within limits. With consistent morning light, evening dim, and timed melatonin, many night-owls can advance their clocks by 30–120 minutes over 2–4 weeks. If your delay is extreme or lifelong, ask about DSWPD evaluation; specialized protocols can help.

4) What is Familial Advanced Sleep Phase Syndrome (FASPS)?

It’s a rare, often inherited tendency to get sleepy very early and wake before dawn, sometimes tied to PER2 or CK1δ variants. Management flips the usual advice: evening bright light, cautious morning light exposure, and behavioral scheduling to delay the clock.

5) Do blue-light glasses fix circadian problems?

They can help reduce evening light’s delaying effect, especially for light-sensitive people, but they’re not a cure. The strongest tools remain bright outdoor light in the morning and low household light at night, alongside consistent routines.

6) Should I take melatonin, and how much?

For shifting timing (not sedation), small doses (∼0.3–1 mg) hours before bedtime are often more effective than large doses at bedtime. Timing matters more than dose. If you’re on other meds or have health conditions, talk with your clinician first.

7) Can meal timing really change my sleep schedule?

It can support it. Peripheral clocks in the liver and gut respond to feeding. Finishing your last meal 3–4 hours before bed and keeping a stable eating window helps align those clocks with the SCN, improving sleep consistency.

8) Is genetic testing useful for my sleep?

It can be interesting for education, and rare clinical variants do exist, but for most people, behavioral timing (light, meals, movement) produces bigger gains than knowing specific SNPs. Suspected clinical disorders should be addressed through a sleep clinic, not consumer testing alone.

9) Why does one late night wreck my whole week?

Because evening light and stimulation can delay the PER/CRY “brake,” pushing melatonin and sleep pressure later. Repeat it a few nights and your clock shifts. Protect 2–3 hours before bed from bright light and high arousal to keep the brakes on schedule.

10) I live near the equator / at high latitude. Does location matter?

Yes. High latitudes (long summer evenings) require stricter evening light control; equatorial regions have stable dawn/dusk that make timing simpler. If your region observes Daylight Saving, plan for springtime evening light to delay sleep and counter it with earlier indoor dimming.

11) Does exercise timing influence my clock genes?

Exercise acts as a secondary zeitgeber. Regular daytime workouts help stabilize rhythms; late-night high-intensity sessions can be alerting and mildly delaying. Aim for a consistent daily activity window that ends well before bedtime.

12) How long until changes “stick”?

Expect days to weeks. Clocks shift gradually—think ~15–30 minutes/day under ideal conditions. Consistency (especially wake time and morning light) matters more than perfection.

Conclusion

Your sleep schedule reflects a conversation between your circadian genes and your daily cues. CLOCK and BMAL1 start the rhythm, PER and CRY stop it, REV-ERB/ROR stabilize it, melanopsin tells it when daylight starts, and kinases like CK1δ fine-tune the pace. Add in hundreds of small polygenic nudges, and you get the familiar spectrum from larks to owls. The empowering part is that these systems are trainable: bright outdoor mornings, dim evenings, regular meals and movement, and smart use of melatonin can move even stubborn clocks in the direction you want. Treat your biology like an ally—build routines that make the right choice the easy choice, most days.

Start tomorrow: wake at your target time, get outdoor light within the hour, set a “screen sunset” two hours before bed, and keep dinner earlier—then repeat for two weeks.

CTA: Ready to design a two-week reset that fits your chronotype? Pick a start date and I’ll map the daily steps.

References

- Transcriptional architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Nature Reviews Genetics (Takahashi JS), 2017. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5501165/

- Genome-wide association analyses of chronotype in 697,828 individuals provides insights into circadian rhythms. Nature Communications (Jones SE et al.), 2019. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-018-08259-7

- GWAS of 89,283 individuals identifies genetic variants associated with self-reporting of being a morning person. Nature Communications (Hu Y et al.), 2016. https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms10448

- Mutation of the Human Circadian Clock Gene CRY1 in Familial Delayed Sleep Phase Disorder. Cell (Patke A et al.), 2017. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5479574/

- Functional consequences of a CK1δ mutation causing familial advanced sleep phase syndrome. Nature (Xu Y et al.), 2005. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15800623/

- Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders: Genetics, Mechanisms and Treatment. Frontiers in Genetics (Liu C & Zhang EE), 2022. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2022.875342/full

- PER3 polymorphism predicts sleep structure and waking performance. Current Biology (Viola AU et al.), 2007. https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(07)00992-X

- Sleep Quality, Sleep Structure, and PER3 Genotype in Young Adults. Journal of Clinical Medicine (Weiss C et al.), 2020. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7479229/

- Crosstalk: The diversity of melanopsin ganglion cell types and their role in circadian rhythms. Current Opinion in Physiology (Sondereker KB et al.), 2020. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9413065/

- Melanopsin-mediated optical entrainment regulates circadian rhythm. Communications Biology (Pan D et al.), 2023. https://www.nature.com/articles/s42003-023-05432-7

- Differences in circadian rhythmicity in CLOCK 3111T/C genetic variants. Sleep (Bandín C et al.), 2012. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4426980/

- Molecular mechanism of the repressive phase of the mammalian circadian clock. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (Cao X et al.), 2021. https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2021174118