Circadian rhythm disorders are conditions where your internal 24-hour body clock falls out of sync with your social or work schedule, leading to trouble sleeping at the “right” times and daytime impairment. In plain terms: your sleep isn’t broken—its timing is. Below you’ll find clear symptoms and evidence-based management for six specific disorders recognized by sleep medicine. Quick definition: circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders are problems of sleep timing (not necessarily sleep quality) caused by misalignment between your internal clock and the external day-night cycle. PubMed

Medical note: This guide is educational and not a substitute for personal medical advice. If you have safety-critical work (e.g., driving, operating machinery) or severe daytime sleepiness, seek professional care promptly.

1. Delayed Sleep–Wake Phase Disorder (DSWPD)

DSWPD means your natural sleep window is shifted later—often by 2–3+ hours—so you can’t fall asleep until late night and struggle to wake at conventional times. People with DSWPD typically sleep well when allowed to follow their preferred schedule (e.g., 2 a.m.–10 a.m.), but school, work, or parenting obligations make this impractical. It’s common in teens and young adults and is frequently mistaken for insomnia or “poor discipline.” Clinicians diagnose DSWPD using history, a sleep diary and/or actigraphy across at least a week; some centers also use dim-light melatonin onset (DLMO) timing to quantify circadian phase. Evidence-based treatments center on timing light and melatonin to advance the body clock and building consistent routines that keep it there. Mayo Clinic

Why it matters

Untreated DSWPD can drive chronic sleep restriction, school or job problems, missed mornings, and mood symptoms. Adolescents are especially vulnerable because biology already nudges their clock later; social schedules (early classes) then conflict with physiology. Prevalence estimates run ~7–16% in adolescents and ~0.13–3.1% in adults, highlighting why targeted management—not generic “sleep hygiene”—is needed. PMC

How to manage (phase-advance approach)

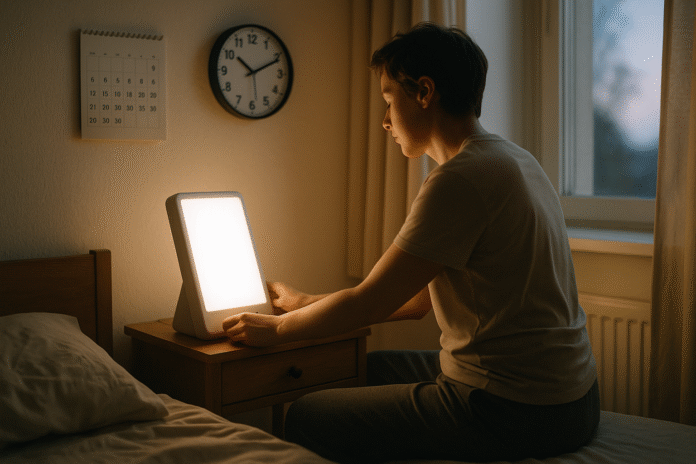

- Morning bright light: Soon after natural wake time (or desired wake time as you shift earlier), get strong light exposure; many studies use 2,000–10,000 lux from a light box for 20–45 minutes. Outdoor morning light works well.

- Strategically timed low-dose melatonin: Taken in the early evening (hours before habitual bedtime), melatonin can advance circadian phase; timing beats dosage for effect. Your clinician should individualize timing around DLMO when available.

- Evening light avoidance: Dim household lighting in the late evening; avoid late bright screens and LED glare. (Blue-weighted light is especially phase-delaying.)

- Gradual schedule shift: Advance bedtime and wake time in small steps (e.g., 15–30 minutes every few days) and lock in wake time daily.

- Treat comorbidities: If insomnia persists, evidence supports CBT-I alongside circadian therapy.

Numbers & guardrails

The AASM guideline suggests strategically timed melatonin for adults (and adolescents) with DSWPD and supports combining post-awakening light with behavioral strategies in youths. Expect multi-week progress; consistency preserves gains.

Bottom line: Start with morning light, dim evenings, and carefully timed melatonin under guidance; anchor wake time and move in steady steps.

2. Advanced Sleep–Wake Phase Disorder (ASWPD)

ASWPD is essentially the mirror image: your sleep window is too early (e.g., 7 p.m.–3 a.m.). People feel very sleepy in late afternoon and wake up before dawn, alert but out of sync with family and work. ASWPD is less common overall and occurs more often in older adults. It has a genetic component in some families. Diagnosis relies on history plus diaries/actigraphy demonstrating stable but advanced timing. Management aims to delay the clock so sleep occurs later, without disrupting total sleep time.

Why it matters

ASWPD can impair evening social life and cause very early awakenings with long predawn hours of solitude. Some patients try napping after work, which further advances bedtime and entrenches the problem. Early evening bright light can help, and safety-critical tasks at predawn hours require caution if residual sleep pressure remains.

How to manage (phase-delay approach)

- Evening bright light: Timed light in the early evening (e.g., for ~1–2 hours) delays circadian phase and helps push bedtime later.

- Morning light control: Use blackout shades or sunglasses during very early morning exposure if it makes you sleepier too early the next night. Keep indoor lights low before desired bedtime.

- Consistent later schedule: Set a realistic target bedtime/wake time and shift gradually. Avoid long evening naps.

Tools & examples

A clinician may suggest an evening light box (~4,000 lux in some studies) or structured outdoor light exposure timed to your circadian phase. Melatonin is not routinely used to delay phase. Track progress with a diary/actigraphy.

Bottom line: Use evening light therapy and careful morning light control to slide your sleep later and maintain it. AASM

3. Irregular Sleep–Wake Rhythm Disorder (ISWRD)

ISWRD features no clear day–night sleep pattern. Instead of one consolidated night sleep, people nap multiple times around the clock, with total 24-hour sleep time often normal for age but fragmented. It’s rare and frequently associated with neurological conditions (e.g., dementia), brain injury, or lifestyle factors that undermine daytime structure. Families often report the person “catnaps all day and wanders all night.” Diagnosis involves diaries/actigraphy showing ≥3 irregular sleep bouts per 24 hours without a dominant nocturnal episode.

Why it matters

Fragmented sleep intensifies caregiver burden, worsens cognition and mood, and increases fall risk in older adults. Because light is the primary time cue, weak daytime light and minimal social routine allow the circadian system to drift, especially in institutional settings with dim indoor lighting.

How to manage (strengthen zeitgebers)

- Daytime bright light: In dementia, 2 hours of 3,000–5,000 lux in the morning for 4+ weeks improves consolidation (fewer daytime naps, more night sleep). Outdoor morning light or high-brightness fixtures can help.

- Regular daytime schedule: Fixed times for meals, activity, and social interaction; avoid late-day dozing.

- Evening light reduction: Dim lights 2–3 hours before bedtime; reduce nocturnal awakenings with good sleep environment and safety measures.

- Caution with sedatives: Guidelines caution against routine sedative-hypnotics in older adults with dementia due to falls and confusion; melatonin efficacy is mixed in this group.

Mini-checklist

- Bright mornings, active days

- Fixed mealtimes and walks

- Gentle evening wind-down; low light

- Safety: nightlights, clear paths, caregiver respite

Bottom line: Build strong, predictable daytime light and routine, keep evenings dim and calm, and avoid sedatives where possible; this combination can meaningfully consolidate sleep. AASM

4. Non-24-Hour Sleep–Wake Rhythm Disorder (N24SWD)

N24SWD occurs when your internal clock runs longer than 24 hours, causing your sleep time to drift later each day (e.g., 30–60 minutes daily). Over weeks, your “night” migrates around the clock. It’s classically seen in totally blind adults who lack retinal light input to the master clock, but it can also occur in sighted individuals. People describe cycling through “good weeks” and “bad weeks” as their sleep temporarily aligns or clashes with the outside world. Diagnosis rests on history plus serial logs/actigraphy showing a free-running pattern; DLMO may confirm a drifting internal phase. Sleep Education

Why it matters

Because the clock never locks to local time, school and work become unpredictable. Mood and performance fluctuate with the drift. For blind adults, targeted therapy can entrain the clock; for sighted adults, options are more limited but still possible with precise timing protocols.

How to manage (entrainment strategies)

- For totally blind adults: Tasimelteon—a melatonin-receptor agonist—is FDA-approved for Non-24 and can entrain rhythms when taken at a consistent clock time before desired sleep; clinicians may also use timed melatonin.

- For sighted individuals: Carefully scheduled bright light (typically soon after target wake) plus evening melatonin may help; adherence is challenging, and specialist supervision improves success.

- Keep timing consistent: Once entrained, protect it with regular light/dark cycles and fixed wake times.

Numbers & guardrails

Trials supporting tasimelteon’s use in totally blind Non-24 (SET/RESET) led to FDA approval; discuss risks, costs, and monitoring with your clinician. For melatonin, timing relative to DLMO is the key determinant of effect. Nevada Medicaid

Bottom line: In blind adults, tasimelteon or timed melatonin can entrain the clock; in sighted individuals, structured light plus melatonin and rigorous routines may stabilize timing.

5. Shift Work Disorder (SWD)

SWD is a circadian misalignment that occurs when work hours require you to sleep at biologically inappropriate times (e.g., night shifts, rotating schedules, very early starts). Not all shift workers have SWD; estimates suggest ~5–10% of shift workers meet criteria with persistent insomnia or excessive sleepiness and functional impairment. SWD raises risk for errors and accidents and is linked to long-term health risks (cardiometabolic disease signals) via chronic circadian disruption. Diagnosis uses history, sleep logs, and exclusion of other sleep disorders (e.g., sleep apnea). PubMed

Why it matters

Sleepiness on duty threatens safety; chronic fatigue impairs mood and cognition. Rotating schedules are hardest to tolerate; permanent nights are slightly easier if daytime sleep can be protected. Employers and clinicians should collaborate on safer scheduling when possible (e.g., forward-rotating shifts, adequate rest periods).

How to manage (alertness + alignment)

- Light management

- On nights: Use bright light during the first half of the shift; wear dark wraparound sunglasses on the commute home; sleep in a dark, quiet room.

- On days off: Aim for partial alignment (e.g., “anchor sleep” window that overlaps workdays and off-days) rather than constant flipping.

- Caffeine & naps: Strategic caffeine early in the shift and brief naps (~20 minutes) can improve alertness; stop caffeine 6 hours before intended sleep.

- Melatonin for day sleep: Some clinicians use strategically timed melatonin before daytime sleep to consolidate rest; judge benefit vs. residual grogginess. AASM

- Prescription wake-promoters: Modafinil/armodafinil are FDA-approved to improve wakefulness in SWD but do not fix circadian misalignment; reserve for persistent sleepiness after optimizing schedule, light, and sleep environment.

Mini-checklist

- Protect 7–9 hours in a dark, cool, quiet room

- Anchor at least 4–5 hours of sleep at a consistent time daily

- Time bright light/caffeine early; block morning light post-shift

- Coordinate with managers for forward-rotating schedules when possible

Bottom line: Combine timed light, caffeine/naps, dark sleep environment, and—when needed—FDA-approved wake-promoters under medical guidance; prioritize safety and consistent anchor sleep. Sleep Education

6. Jet Lag Disorder (JLD)

Jet lag follows rapid travel across time zones: internal time lags behind the destination day-night cycle, causing insomnia, daytime sleepiness, impaired concentration, and digestive upset. Eastward travel usually feels harder (you must fall asleep earlier than your body wants); westward feels easier but still disrupts sleep. Severity scales with the number of time zones crossed and how tightly scheduled your trip is. Most people improve over 3–5 days, but athletes, executives, and crew with repeated trips benefit from phase-shift planning.

Why it matters

Jet lag reduces alertness and decision-making—critical for business travelers and those operating vehicles soon after arrival. Planning when to seek or avoid light at your destination materially speeds recovery; in some cases, short courses of medication are appropriate.

How to manage (plan by direction)

- Start shifting before you fly: Move bedtime/wake time 30–60 minutes toward destination time for 2–3 days if feasible.

- Light timing at destination

- East → seek morning light, avoid late-evening light the first days.

- West → seek late-afternoon/early-evening light, avoid early morning light initially.

- Caffeine & naps: For alertness, 200 mg caffeine every ~4 hours in daytime, stopping 6 hours before bedtime; brief naps (~20 minutes) can help.

- Melatonin: Multiple trials and a Cochrane review show melatonin is effective for preventing or reducing jet lag when taken close to destination bedtime; short-term use appears safe for most adults.

- Hydration, alcohol limits, meals: Stay hydrated, go easy on alcohol, and eat on local time. NHS guidance aligns with these practical steps.

Bottom line: Shift sleep gradually, time light correctly by direction, use caffeine/naps judiciously, and consider melatonin near destination bedtime for trips ≥5 time zones (especially eastbound).

FAQs

1) How do I know if I have a circadian disorder versus insomnia?

Circadian disorders primarily involve timing: you sleep well at “wrong” hours but poorly at desired hours. If you can sleep normally when allowed your preferred schedule (e.g., weekends, holidays), think circadian. Insomnia persists regardless of timing. A sleep diary/actigraphy for 1–2 weeks helps distinguish them; some clinics measure DLMO to pinpoint internal time.

2) What tests should I expect at a sleep clinic?

Most diagnoses rely on history plus sleep logs and actigraphy; labs may order DLMO testing or (if another disorder is suspected) sleep studies. Expect counseling on light, melatonin, and schedule design. Polysomnography isn’t routinely needed unless symptoms suggest apnea, periodic limb movements, or parasomnia.

3) Is melatonin safe and how should I time it?

Short-term melatonin is generally well-tolerated; timing is pivotal: earlier = advances the clock, later = delays or does nothing. For DSWPD, clinicians time it hours before habitual bedtime; for jet lag, close to destination bedtime; for blind Non-24, tasimelteon or melatonin may be used to entrain. Always discuss medications with your clinician, especially if pregnant, older, or on interacting drugs.

4) Do blue-light-blocking glasses fix circadian problems?

Evening light reduction helps, but evidence that consumer blue-blocking lenses alone “cure” circadian disorders is mixed. Prioritize overall light intensity and timing (dim evenings, bright mornings) over gadget-specific claims; use glasses only as part of a broader protocol.

5) Can I treat shift work disorder with caffeine alone?

Caffeine improves alertness but doesn’t realign your clock. Use it strategically early in shifts and stop ~6 hours before sleep. Combine with timed light, dark sleep environment, and possibly planned naps; medications like modafinil/armodafinil are options when non-drug measures are optimized but daytime sleepiness persists.

6) How long does jet lag last?

Many recover within 3–5 days, but it depends on direction and number of time zones crossed. Eastbound trips generally feel harder. A plan for light timing, caffeine, and melatonin can shave days off recovery. Sleep Education

7) What’s the role of light therapy boxes?

Light therapy is a core tool. Morning light advances (useful in DSWPD), evening light delays (useful in ASWPD). In dementia-related ISWRD, strong morning light (3,000–5,000 lux for ~2 hours) across weeks improves consolidation. Follow product safety guidelines and clinician timing advice.

8) Is Non-24 only in blind people?

No. While it’s most common in totally blind adults, sighted people can develop Non-24 (rarely). Blind adults have an FDA-approved option (tasimelteon) that can entrain the clock; sighted cases use carefully timed light plus melatonin under specialist care.

9) Are there risks from long-term circadian disruption?

Shift work and chronic misalignment are associated with higher risks of errors, injuries, and long-term cardiometabolic issues; causality is complex, but risk-reduction through better scheduling, light, and sleep protection is prudent for workers and employers. CDC

10) When should I seek specialist help?

If your schedule is incompatible with obligations, you’re falling asleep unintentionally, or safety is at stake (driving, machinery), see a sleep clinician. Persistent problems despite light/melatonin timing, suspected comorbid sleep apnea, or the need for work letters/accommodations also warrant referral. Sleep Education

Conclusion

Circadian rhythm disorders are fundamentally timing problems—not willpower failures. Because the master clock is responsive to light, behavior, and (in some cases) medications, small but precise changes create outsized benefits. For DSWPD and ASWPD, think light on the correct side of sleep (morning to advance, evening to delay), melatonin timed for phase-shift, and consistency to lock gains. For ISWRD, bright structured days and dim calm evenings help consolidate sleep, especially in dementia. For Non-24, tasimelteon or timed melatonin can entrain blind adults; sighted cases need specialist-led protocols. For SWD and jet lag, direction-specific light timing, caffeine/naps, and sleep-environment engineering speed adaptation and protect safety. The common thread is planning: map where your clock is, where you need it to be, and move it deliberately. If you’re stuck, a sleep clinician can measure your phase and tailor timing precisely.

Action step: Choose one target (light, melatonin timing, or schedule) this week, implement it consistently for 14 days, and track your sleep/wake times—tiny, well-timed nudges reset even stubborn clocks.

References

- International Classification of Sleep Disorders—Third Edition (ICSD-3) & Text Revision. American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM). 2014; TR supplemental 2023. and https://aasm.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/ICSD-3-Text-Revision-Supplemental-Material.pdf AASM

- Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Intrinsic Circadian Rhythm Sleep-Wake Disorders (ASWPD, DSWPD, N24SWD, ISWRD): An Update for 2015. AASM, J Clin Sleep Med. 2015. AASM

- Treatment of Circadian Rhythm Sleep–Wake Disorders. Sun SY, Front Neurosci. 2022. PMC

- Delayed Sleep–Wake Phase Disorder (patient page). SleepEducation.org (AASM). Reviewed Oct 2020. Sleep Education

- Advanced Sleep–Wake Phase Disorder (patient page). SleepEducation.org (AASM). Sleep Education

- Irregular Sleep–Wake Rhythm Disorder (patient page). SleepEducation.org (AASM). and MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia, updated May 7, 2024: Sleep EducationMedlinePlus

- Non-24-Hour Sleep-Wake Rhythm Disorder. Abbott SM, Curr Sleep Med Rep. 2019. PubMed

- HETLIOZ® (tasimelteon) U.S. Prescribing Information (Non-24 in adults). FDA label (2019/2020). and https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/214517s000lbl.pdf Access Data

- Shift Work: Health and Safety Risks. CDC/NIOSH Work Hours, 2020–2024 modules. and https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/work-hour-training-for-nurses/longhours/mod3/15.html CDC

- PROVIGIL® (modafinil) and NUVIGIL® (armodafinil) FDA labels—indication for Shift Work Disorder. FDA. and https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/021875s021lbledt.pdf Access Data

- Jet Lag—CDC Yellow Book 2025. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated Apr 23, 2025. CDC

- Melatonin for the prevention and treatment of jet lag. Cochrane Review (Herxheimer & Petrie), updated; and open-access summary. and Cochrane LibraryPMC

- Jet lag (self-care). NHS. nhs.uk