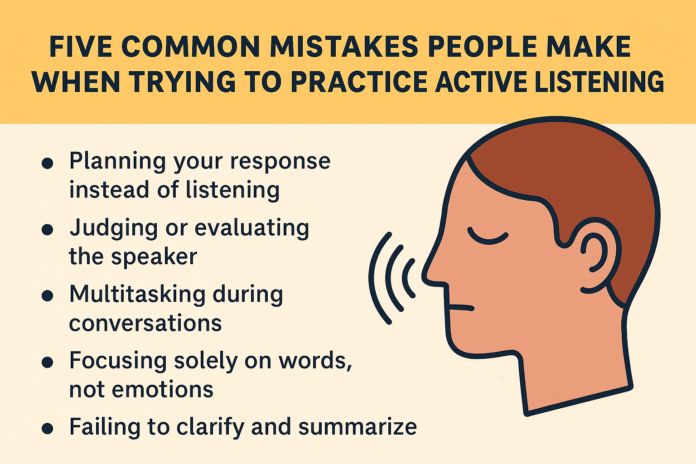

Active listening is more than just hearing words; it’s a choice that helps individuals understand, feel, and connect with each other. On the other hand, a lot of well-meaning people fall into common traps that make it hard for them to actually listen. We’ll speak about the five most common mistakes individuals make when trying to practice active listening in this long essay. We’ll also talk about why these mistakes arise and how to avoid them based on data. We will utilize peer-reviewed research, guidance from top experts in the area, and real-life examples to help you learn how to properly listen in every conversation and feel good about it.

Why it’s crucial to pay attention

Before you can perceive the problems, you need to know what active listening does for you in your personal and professional life.

- People will like you and trust you. People are more willing to discuss and work together when they sense their opinions are being acknowledged (Rogers & Farson, 2015).

- Lessens the amount of confusion. Problems with communication are to blame for up to 70% of mishaps at work. That can help (Society for Human Resource Management, 2020).

- Makes it easy to work out differences. You make it safe to tackle challenges by acknowledging their concerns (Fisher & Ury, 2011).

- Raises your emotional intelligence (EQ). You learn more about yourself and how to regulate yourself when you show empathy (Goleman, 1998).

Mistake #1: Thinking about what to say instead of listening

Why It Happens: Cognitive strain. We can communicate faster than our brains can think, so they have time to come up with comebacks (Baddeley, 2012).

- How to Do It. People tend to “perform” well when the stakes are high, like when they are negotiating or interviewing for a job. This means that instead of listening, they mentally write down what they want to say.

- A tiny mistake had big effects. You might miss sensations, hidden meanings, or essential information.

- They assumed they weren’t interested. If you are impolite or cut someone off, it means you are impatient or arrogant.

How to Get Over It

- Take a break for a minute. Wait one to two seconds after the speaker is done before you say anything (University of California, 2017).

- Taking notes. Instead of thinking about your answer, write down some important words to assist you stay focused.

- Living with mindfulness. Meditating for just five minutes a day will help you stay in the present (Kabat-Zinn, 2003).

Mistake 2: Making a judgment about the speaker

Why It Happens: Filters That Work Automatically. We all have schemas and biases that help us quickly understand what we hear (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974).

- A error made by an expert. People who know a lot about a subject typically make quick decisions without completely grasping the problem.

- One of the outcomes is being defensive. If the speaker thinks they are being judged, they can stop talking.

- That was not learning. People don’t want to know more when they get early reviews.

How to Get Over It

- Don’t make a choice yet. Tell yourself on purpose, “I’ll get clear before I make a choice.”

- Don’t use prompts that tell you what to do. “Can you tell me more about that?” is a question that doesn’t have a clear answer.

- Act like a beginner. Act like you’re hearing about the subject for the first time; being interested will make you pay attention.

Mistake 3: Talking to someone while doing other things

Why It Happens: Digital Distractions. You get calls and notifications all the time from your smartphone, laptop, and other devices.

- What people think about how well it functions. We are proud that we can do a lot of things at once.

- One impact is that attention is broken up. When you are “half-listening,” it is harder to retain and grasp things (Risko & Gilbert, 2016).

- Stress in a love connection. When people “compete” with technologies, they feel less important.

How to Move On

- Create “No-Device” Areas. When you’re at a meeting or talking to someone, turn off all of your electronic gadgets.

- Give a clear signal of interest. When you talk to someone, look them in the eye, nod, and mirror their body language (Matsumoto & Hwang, 2013).

- Time to block. Take some time to listen without using any devices.

Mistake 4: Only paying attention to words and not feelings

Why It Happens: Verbal Bias. We don’t always pay attention to how someone sounds or moves when we hear what they say.

- Feeling bad. Seeing someone else with powerful feelings can make you feel anxious or awkward.

Results

- Not receiving everything. According to Mehrabian (1972), emotions make approximately 93% of the meaning of a statement.

- Lost opportunity to be understanding. Even if you don’t know how they feel, you may help them by giving them rational answers when they need emotional support.

How to Move On

- Use the “Feel-Heard” way. You should not just repeat what was said, but also how it was expressed: “It sounds like you’re upset about…”

- Learn to read people’s body language. Know how your body language, gestures, and facial expressions alter (Burgoon, Guerrero, & Floyd, 2016).

- Know how you feel. If you say something like “That must have been hard,” people will trust you and feel safe.

Mistake 5: Not being clear and not giving a summary

Why It Happens: We tell ourselves, “I got it,” even when we don’t.

- Time stress. It feels like a waste of time to stop and check things when you’re busy.

What occurs

- Not being able to talk to one another. People mess up or argue when things aren’t obvious.

- Anger from viewers and listeners. Speakers could think that no one is listening or comprehending them if there are no feedback loops.

How to Get Over It

- Change the Words. “So, what do you mean by that?”

- If you want to be clear, ask questions. When you mention X, do you mean Y or Z?

- Short offers. At the end of the discussion, go over the important topics again: “In short, here’s what we need to do next…”

Frequently Asked Questions

- What is the difference between hearing and actively listening?

Your body hears when sound waves reach your eardrums. When you actively listen, you really pay attention to what someone is saying and how they feel about it. It needs both mental focus and actions. - Is it possible to learn how to listen actively, or is it something you were born with?

You can learn how to actively listen by practicing, getting instruction, and being conscious of your own feelings and thoughts. Structured techniques and feedback can help even persons who are naturally sympathetic. - How long does it take to properly learn how to listen?

Some changes might emerge in a few weeks, but it usually takes 3 to 6 months of constant training and practice in the real world to actually learn how to listen well. - Is it disrespectful to ask someone to say what they said again?

No, not if you do it with respect. “I want to make sure I heard you right.” “Could you please say that again?” shows that you really want to comprehend. - How do I handle my feelings when I’m having a hard time?

You may say something like, “I can tell you’re mad.” Do you want to chat more about what’s wrong? This demonstrates that you care and are in charge.

Last Thoughts

It’s not easy to learn how to actively listen, and we have to battle the impulse to write down our thoughts, do more than one thing at a time, or judge. You may improve how you talk to people, make your connections stronger, and be known as a loving and trustworthy communicator if you avoid these five frequent blunders and follow the suggestions above. Keep in mind that the most important part about being an expert is not talking but listening.

References

- Baddeley, A. (2012). Working Memory: Theories, Models, and Controversies. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100422

- Burgoon, J. K., Guerrero, L. K., & Floyd, K. (2016). Nonverbal Communication. Routledge.

- Fisher, R., & Ury, W. (2011). Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In (3rd ed.). Penguin.

- Goleman, D. (1998). Working with Emotional Intelligence. Bantam.

- Kabat‑Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR). Constructivism in the Human Sciences, 8(2), 73–107.

- Matsumoto, D., & Hwang, H. (2013). Nonverbal Communication: Science and Applications. Sage.

- Mehrabian, A. (1972). Nonverbal Communication. Aldine-Atherton.

- Rogers, C., & Farson, R. (2015). Active Listening. In The Communication Book. HarperCollins.

- Risko, E. F., & Gilbert, S. J. (2016). Cognitive Offloading. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(9), 676–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2016.07.002

- Society for Human Resource Management. (2020). The Cost of Poor Communication. https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr-topics/organizational-and-employee-development/pages/the-cost-of-poor-communication.aspx

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124–1131. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.185.4157.1124