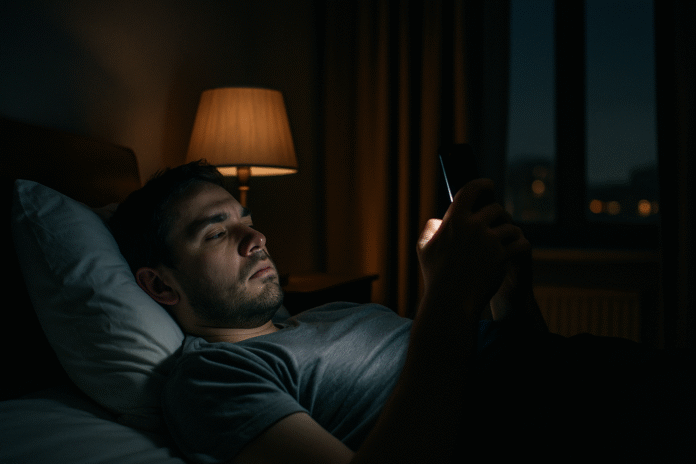

Scrolling feels harmless, but social media right before bed changes how your brain winds down, when your body clock thinks “night” starts, and how well memories and emotions are filed while you sleep. In short: social media before sleep delays your circadian clock, suppresses melatonin, heightens mental/emotional arousal, and fragments sleep—leading to foggier thinking and mood the next day. This guide explains 12 specific brain effects and gives practical, low-effort swaps you can use tonight. (This article is educational, not medical advice. If sleep issues persist, see a clinician.)

Quick start (one-minute plan): Turn on Do Not Disturb (DND), set a 45–90 minute digital curfew, charge your phone outside the bedroom, and keep a paper “parking lot” by the bed to offload late-night thoughts. These simple moves remove the strongest triggers while protecting your brain’s natural sleep chemistry.

1. It delays your body clock and sleep onset

Late-night social media pushes your brain’s master clock later and makes it harder to fall asleep on time. Light from screens and mentally engaging content both signal “it’s still daytime,” delaying the release of sleep-promoting hormones and shifting your circadian phase. Studies show evening exposure to light-emitting devices can push your biological night later, reduce evening sleepiness, and make next-morning alertness worse. The result is a mismatch between when you want to sleep and when your brain is ready, a pattern that snowballs into chronic late bedtimes and groggy mornings. If you’ve ever glanced at the clock after “just one more reel” and wondered where an hour went, that’s circadian delay plus cognitive arousal working together. The fix isn’t only “less phone”; it’s earlier darkness, earlier wind-down, and more consistent cues that teach your brain when night starts.

1.1 Why it matters

- Circadian delay shifts your “sleep gate” later, raising sleep latency and cutting total sleep time.

- Next-day outcomes include slower reaction time, reduced vigilance, and mood lability—especially on work/school days.

- Compounded over weeks, it resembles social jet lag: a weekday–weekend body-clock tug-of-war.

1.2 Numbers & guardrails

- Evening light from e-readers delayed circadian timing and reduced next-morning alertness in controlled lab conditions.

1.3 What to do instead

- Create a “lights-down” window 60–90 minutes pre-bed (lamps dimmed, screens off).

- Anchor wake time, even on weekends, to pull your clock earlier.

- Swap to non-emitting wind-downs: print book, stretching, or audio-only story.

Bottom line: Treat darkness and quiet, not just “time in bed,” as the brain’s nightly clock cue.

2. It suppresses melatonin at surprisingly low light levels

Your pineal gland’s melatonin release is exquisitely sensitive to evening light. Research indicates that on average 50% melatonin suppression can occur at <30 lux—a dim indoor level many people exceed with a phone close to the face. Even when screens shift toward warmer hues, brightness and timing still matter; some trials show that using blue-light filters like Night Shift results in no meaningful sleep improvement compared with not using the phone at all in the hour before bed. Translation: filtering color alone won’t fully protect melatonin if you’re still bright-screening late. Managed Healthcare Executive

2.1 Numbers & guardrails

- ~50% melatonin suppression at <30 lux across individuals (with notable variability).

- Color temperature adjustments help less than cutting overall brightness and exposure time.

2.2 A practical mini-checklist

- Brightness: Drop to the minimum; use black background (dark mode) and reduce overall screen luminance.

- Distance: Keep the device farther from eyes; avoid face-close angles in bed.

- Timing: Stop screens ≥60–90 minutes before sleep; if you must read, choose paper or true e-ink.

Bottom line: Warm tint ≠ dark. Dim earlier or go screen-free to let melatonin rise on time.

3. It ramps up cognitive arousal—even if cortisol doesn’t spike

The endless novelty and social feedback loops of feeds keep cortical networks alert. Likes, comments, and short-form video exploit variable rewards, sustaining attention and mental chatter. Not every bout of scrolling triggers a measurable physiological stress response; in one controlled study, 20-minute sessions of social media or YouTube didn’t raise cortisol or heart rate. But you don’t need a cortisol spike to struggle with sleep: cognitive arousal (busy thoughts, planning replies, “one more clip”) is enough to block sleep onset. Think of it as the brain idling at high RPM—quiet outside, noisy inside. The antidote is designing your evening for low stimulation and clean stopping points, not willpower alone.

3.1 Tools/Examples

- Friction adds freedom: Log out nightly, move apps off the first screen, or use app timers set to expire by 9–10 p.m.

- Content diet: Save heavy topics for daytime; prefer calming audio at night (music, nature sounds, audiobooks).

3.2 Mini case

- A student who swapped 45 minutes of reels for a 20-minute podcast + 10 minutes of journaling cut sleep latency from “>30 minutes” to “~10 minutes” within two weeks (self-tracked).

Bottom line: Your brain can be “wired” without being “stressed.” Reduce novelty and interaction late to drop mental RPMs.

4. It fuels “revenge bedtime procrastination”

When your day feels overscheduled, late-night scrolling becomes stolen “me time.” That’s revenge bedtime procrastination—knowingly trading sleep for leisure to reclaim control. It’s common, grew during the pandemic, and shows up as “I know I’m tired, but I’m not done doomscrolling.” The behavior keeps the brain alert past the sleep gate, making tomorrow’s fatigue more likely and the cycle self-reinforcing. The solution isn’t only grit; it’s daytime micro-breaks, evening rituals that feel rewarding, and boundaries that make stopping easier than continuing. As of August 2025, major sleep education sites describe RBP as a frequent driver of delayed bedtimes in heavy tech users. PMC

4.1 Why it matters

- Chronic delay erodes total sleep time and attention the next day.

- Emotional costs include guilt and stress, which further hinder sleep.

4.2 How to do it

- Schedule “me time” earlier: 20–30 minutes after dinner.

- Set a bedtime alarm with an unmistakable tone and automatic Focus mode.

- Use a “power-down hour”: 20 minutes prep (clothes/coffee), 20 hygiene, 20 relax. WIRED

Bottom line: Replace late-night “revenge” with earlier, intentional leisure so your brain doesn’t need to reclaim it at midnight.

5. It amplifies social comparison and FOMO that keep the mind racing

Social media is engineered for social salience—peers, status, and belonging—which primes comparison and fear of missing out (FOMO). At night, those cues magnify: your prefrontal “filter” is tired, and emotional salience keeps looping. Research links heavier social media use and FOMO with poorer sleep quality and more nighttime rumination. U.S. public health advisories also warn that social platforms can adversely affect youth well-being in part through sleep disruption. To sleep, your brain needs safety and closure; FOMO delivers the opposite. Reducing nighttime exposure while addressing daytime belonging pays off fast.

5.1 Numbers & guardrails

- Recent studies report higher FOMO in those using social media most days vs. weekends only, with sleep quality differences tracking that pattern. PMC

5.2 Try this instead

- Batch catch-up: Check group chats once in early evening, not at 11:30 p.m.

- Close the loop: Write a quick “tomorrow list” to park unfinished thoughts.

- Belonging by day: Schedule a real-world touchpoint (coffee/walk) to lower night cravings.

Bottom line: Comparison and FOMO are arousal engines. Put them on a daytime schedule so your brain can power down at night.

6. It fragments sleep via pings, pickups, and nocturnal checking

Even after you fall asleep, notifications can jolt you into light sleep or brief awakenings. Teens and young adults are especially vulnerable, with studies showing that nighttime smartphone engagement relates to more wake events and worse sleep quality. Review papers note that being contacted at night—or anticipating it—keeps arousal systems on standby. Practically, the “phone under the pillow” binds your sleep to the network’s activity level. Breaking that tether (DND, silenced alerts, phone out of reach) protects sleep continuity—critical for memory consolidation and emotional regulation. UNC DSN Lab

6.1 Mini-checklist

- DND or Sleep Focus: Auto-enable nightly; whitelist true emergencies only.

- Out of room: Charge your phone in the hall; use a $10 alarm clock.

- Batch sync: Disable background refresh overnight.

6.2 Why it matters to the brain

- Fragmentation reduces slow-wave and REM stability, which support memory and mood processing.

Bottom line: The quietest notification is a phone you can’t hear—or reach—from bed.

7. It worsens next-day attention, memory, and cognitive control

Sleep lost to late-night scrolling shows up as sluggish attention and poorer working memory the next day. Meta-analyses and reviews conclude that sleep restriction and deprivation impair memory formation and cognitive control, with hippocampal circuits notably affected. That’s why trivial nighttime habits can have non-trivial effects on exams, driving vigilance, and complex problem-solving. Your brain’s “save button” (consolidation) runs at night; pushing bedtime past the sleep gate or fragmenting the night interrupts that process. Protecting one full, high-quality night often restores measurable performance.

7.1 Numbers & guardrails

- Restricting sleep to 3–6.5 hours vs. 7–11 hours yields measurable memory deficits (small but reliable effects). ScienceDirect

7.2 Tools/Examples

- Phone drop time = 90 minutes before target bedtime.

- Task swap: Short, non-interactive audio or light stretching beats scrolling.

Bottom line: If you care about tomorrow’s brain, protect tonight’s sleep cycle from the infinite scroll.

8. It skews emotional processing and next-day mood

Sleep helps your brain recalibrate emotions—sorting what to remember and smoothing the intensity. When social media cuts sleep short or chops it up, emotional memory processes can shift, sometimes preserving negative tone more than neutral. Recent reviews highlight mixed—but converging—evidence that sleep opportunities after learning support emotional memory, and that sleep loss can bias affect. Fragmented REM and insufficient slow-wave sleep can both play roles, with new work suggesting complementary functions. In everyday terms: less quality sleep = edgier responses, stickier negative content, and less resilience to stressors tomorrow. PMC

8.1 Why it matters

- Nightly “emotional reset” lets the amygdala and prefrontal cortex re-balance.

- Sleep loss may increase pain sensitivity and negative bias the next day. ScienceDirect

8.2 What to do instead

- Evening content audit: Avoid emotionally charged topics after 9 p.m.

- Wind-down ritual: 10–15 minutes of breathwork or a warm shower.

Bottom line: Protect sleep architecture and you protect tomorrow’s emotional steering.

9. It lowers heart rate variability (HRV) and keeps your brain “on alert”

Using smartphones in bed is associated with changes in autonomic balance—higher heart rate, reduced HRV, and more wake after sleep onset—signs your nervous system is skewed toward alertness. While individual responses vary, the pattern fits how stimulating content plus near-eye light nudge the body into a light-sleep, light-alert limbo. Over time, this can condition your brain to expect micro-engagements at night, making deep sleep less accessible. Shifting to non-visual, low-salience wind-downs helps restore parasympathetic dominance so sleep can deepen.

9.1 Tools/Examples

- Audio-only wind-downs: Guided relaxation, ambient sounds.

- Breath ratio: 4-6 breaths/minute (e.g., 4s inhale, 6s exhale) for 5–10 minutes.

9.2 Mini-checklist

- No phones in bed; if awake >20 minutes, get up, dim light, and do a calm activity until sleepy.

Bottom line: Your autonomic nervous system follows your habits; give it low-arousal cues before bed.

10. It squeezes REM and slow-wave sleep when bedtimes drift late

Even if total time in bed looks similar, pushing sleep later trims early-night slow-wave sleep or late-night REM—both critical for learning and emotional health. Newer research suggests complementary roles for SWS and REM in consolidating emotional memories, with REM possibly involved in pruning affect while SWS stabilizes detail. Social media doesn’t directly delete REM, but the timing and fragmentation it introduces can shift stage proportions. Protect your “bookends”: the first and last 90 minutes of sleep. PMC

10.1 Numbers & guardrails

- Two nights of recovery sleep can restore some hippocampal functions after deprivation—useful, but not a license to binge scroll on weekdays.

10.2 Try this instead

- Reverse alarm: A chime at T-90 to start wind-down.

- Consistency streak: Keep wake time fixed for 14 days; let bedtime pull earlier naturally.

Bottom line: When you protect both the start and end of your sleep, the middle tends to take care of itself.

11. It hits adolescents and young adults harder

Teens’ brains are naturally phase-delayed and extremely online, a combo that magnifies late-night scrolling effects. Authoritative bodies recommend 8–10 hours of sleep for 13–18-year-olds, yet the majority fall short, with social media commonly cited as a contributor. Reviews and meta-analyses link heavier social media/electronic media use to poorer sleep and mental health in youth (with some conflicting findings). For parents and educators, the most effective steps are structural: household charging stations, wi-fi curfews, and modeling adult behavior. For students, the move is reclaiming earlier leisure so midnight doesn’t feel like the only “free” time.

11.1 Region-neutral guardrails

- Screens down after homework, not after midnight.

- DND schedules synced across family devices.

- Late-night lifeline: One offline activity that truly feels like downtime (drawing, music, stretches).

11.2 Numbers & guardrails

- Sleep orgs continue to report widespread teen sleep insufficiency as of 2024–2025.

Bottom line: For developing brains, earlier curfews and predictable routines pay especially large dividends. PMC

12. It trains your brain to associate the bed with wakefulness

Using a phone in bed teaches your brain that the bed is a place to think, watch, and react—not to sleep. In cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), stimulus control reverses that conditioning: bed for sleep and sex only; get up if you can’t sleep; keep a consistent wake time. Decades of evidence and current guidelines endorse this approach, including growing support for digital CBT-I apps. The takeaway is simple: protect the bed–sleep link. If scrolling happens, move it out of the bedroom and off the bed.

12.1 Mini-checklist (stimulus control)

- Go to bed only when sleepy; get out of bed if awake ~20 minutes.

- Use the bed/bedroom for sleep and sex only; no phones in bed.

- Keep a fixed wake time; avoid long daytime naps.

12.2 Tools/Examples

- App-based CBT-I programs show improvements vs. education-only controls; some include sleep restriction, relaxation, and coaching. JMIR

Bottom line: Your brain follows the rule you teach it most: “In bed, we sleep.” Make that rule obvious again.

FAQs

1) How long before bed should I stop using social media?

Most people benefit from a 60–90 minute digital curfew. That window allows melatonin to rise, arousal to drop, and your circadian clock to lock in “night.” Warmer screen tints help less than lowering brightness and stopping earlier. If 90 minutes feels impossible, start with 30 minutes and push earlier by 10–15 minutes per week.

2) Does Night Shift (or blue-light filters) solve the problem?

Not fully. Color-shifting can reduce short-wavelength light, but brightness and timing still matter. In young adults, using a smartphone with Night Shift did not produce better sleep than not using the phone at all in the hour before bed. Warm tint ≠ protection if you’re still scrolling late.

3) If I must be on my phone late, what’s the least-bad way?

Lower brightness to minimum, switch to dark mode, increase viewing distance, and prefer non-interactive audio (downloads) over visual, social feeds. Use DND, disable badges, and avoid emotionally charged content after 9–10 p.m. None of this is perfect, but it reduces melatonin suppression and cognitive arousal.

4) Is it the light or the content that hurts sleep more?

Both, and they interact. Light delays melatonin and your clock; stimulating content sustains mental activity. You can feel wide awake with minimal light if the content is engaging, and bright light alone can delay the sleep gate even with “neutral” content. Designing for dark + dull is ideal. PMC

5) Do quick 15–20 minute scrolls matter?

Physiologically, a short session may not spike cortisol in a lab, but real-world scrolling rarely stops exactly at 20 minutes, and cognitive arousal can linger. If you keep it brief, use strict app timers and a non-bed location so the session has a clean end.

6) What’s the best single change for teens?

Charge devices outside the bedroom and set a house-wide DND schedule. Teens need 8–10 hours; late-night contact and notifications are strongly linked to poorer sleep. Modeling adult behavior (parents’ phones out, too) amplifies the effect.

7) Can social media ever help sleep?

Indirectly, yes—during the day. Positive social support, humor, and education can lower stress that otherwise fuels night-time arousal. But near bedtime, the costs usually outweigh benefits. If you want supportive content at night, choose pre-downloaded, non-interactive audio.

8) Is doomscrolling a willpower problem or a design problem?

Mainly design plus unmet needs. Variable rewards and bottomless feeds keep you hooked; RBP arises when daytime needs go unmet. Change the environment: log out nightly, move apps off the home screen, and schedule earlier “me time.”

9) Does one late night really hurt memory?

A single short night can impair new memory formation and attention the next day. Two nights of recovery sleep can help, but frequent short nights accumulate cognitive costs. Protect school/work-night sleep; let weekends be for recovery, not for staying up later. Nature

10) Are blue-light-blocking glasses worth it?

Evidence is mixed; results vary by lens quality and brightness. Glasses don’t address content engagement or late timing, which are big pieces of the problem. Dimming and earlier stopping remain higher-leverage steps. (If you use glasses, pair them with a digital curfew.)

11) What about people who have to be online late (shift workers, global teams)?

Emphasize audio-only where possible, strict brightness control, and robust morning light exposure after the sleep period to re-anchor your clock. Keep devices out of bed and use DND to prevent mid-sleep pings. On off-days, stabilize your sleep window to avoid repeated re-shifting. PMC

12) If I already have insomnia, where should I start?

Ask your clinician about CBT-I or consider vetted digital CBT-I programs. Core components—stimulus control, sleep restriction, relaxation, and cognitive strategies—reverse the “bed = awake” learning and reduce pre-sleep arousal. Apps can be effective when structured and evidence-based.

Conclusion

Social media before sleep isn’t just “a bad habit”—it’s a powerful set of cues that tell your brain to stay awake, push your body clock later, and hold onto mental noise. Light from screens suppresses melatonin at low levels; interactive, emotionally salient content keeps cortical networks busy; and late-night pings fragment the sleep stages that file memories and regulate mood. The fix is less about iron will and more about smart design: make the right choice the easy choice. Start with a 60–90 minute digital curfew, DND on a schedule, and the phone out of the bedroom. Replace late feeds with low-stimulation rituals—paper pages, breathwork, or audio. If insomnia has taken root, stimulus control and CBT-I rebuild the bed-sleep link.

Protecting tonight’s wind-down protects tomorrow’s brain—attention, memory, mood, and motivation. Choose one swap tonight, note how you feel tomorrow, and iterate weekly. Your one-line CTA: Power down by T-90, put the phone to sleep outside your room, and let your brain do the rest.

References

- Chang A-M, Aeschbach D, Duffy JF, Czeisler CA. Evening use of light-emitting eReaders negatively affects sleep, circadian timing, and next-morning alertness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015. PNAS

- Chang A-M et al. PubMed record for above PNAS trial. National Library of Medicine. 2015. PubMed

- Phillips AJK, Vidafar P, Burns AC, et al. High sensitivity and interindividual variability in the response of the human circadian system to evening light. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2019. PNAS

- St. Hilaire MA, Lockley SW, et al. The spectral sensitivity of human circadian phase resetting and melatonin suppression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2022. PNAS

- Duraccio KM, Krietsch KN, Chardon ML, et al. Does iPhone Night Shift mitigate negative effects of smartphone use on sleep? Sleep Health. 2021. ScienceDirect

- Oppenheimer S, Shafran N, et al. Social media does not elicit a physiological stress response in the lab. PLOS ONE. 2024. PLOS

- Garrett SL, Telzer EH, et al. Links Between Objectively-Measured Hourly Smartphone Use and Adolescent Wake Events Across Two Weeks. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2023. Taylor & Francis Online

- Bauducco S, et al. A bidirectional model of sleep and technology use. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2024. ScienceDirect

- Kheirinejad S, et al. Quantitative analysis of smartphone use effect on sleep and cardiac markers. (Open-access study reporting latency/HR/HRV changes). 2022. PMC

- Newbury CR, Monfort SS, et al. Sleep deprivation and memory: meta-analytic reviews. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2021. PMC

- Rawson G, et al. Sleep and Emotional Memory: A Review of Current Evidence. Current Sleep Medicine Reports. 2024. SpringerLink

- Yuksel C, et al. Both slow-wave and rapid eye movement sleep contribute to emotional memory consolidation. Communications Biology (Nature). 2025. Nature

- U.S. Surgeon General. Social Media and Youth Mental Health: An Advisory. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2023. HHS.gov

- Sleep Foundation. Revenge Bedtime Procrastination. Updated July 15, 2025. Sleep Foundation

- Sleep Foundation. Electronic Media Use and Sleep Quality: Meta-analysis. JMIR, 2024 summary. JMIR

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM). Teens need 8–10 hours per night. Sleep Education. 2025. Sleep Education

- Edinger JD, et al. Behavioral and psychological treatments for chronic insomnia disorder in adults: clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2021. PMC

- AASM. Digital CBT-I platforms and characteristics. 2024. AASM

- Zhang C, et al. Digital Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia Using a Smartphone App: Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Network Open. 2023. JAMA Network

- Siebers T, et al. Daytime vs. pre-/post-bedtime smartphone use and adolescent sleep quality. (Study report). 2024. journals.sagepub.com