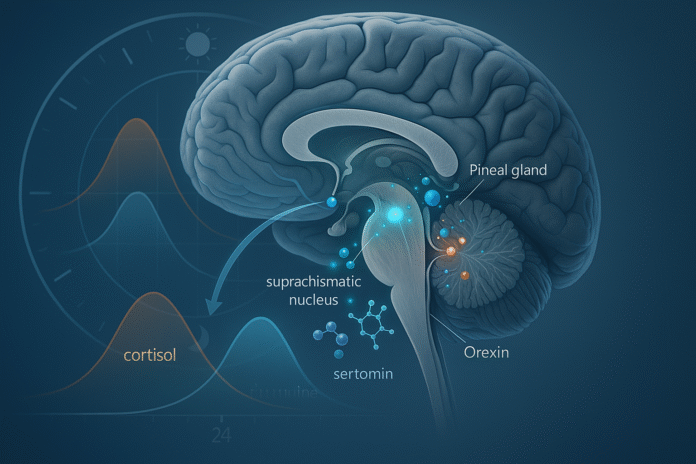

Circadian rhythms are the body’s 24-hour programs for sleep, alertness, body temperature, hormone secretion, and metabolism. They’re coordinated by a master clock in the brain—the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN)—that reads morning light and nightly darkness, then synchronizes organ “clocks” through timed neural and hormonal signals. In practical terms: light resets the clock, and hormones and neurotransmitters carry out the schedule. This guide explains the biology behind circadian rhythms through 9 key chemical messengers you’ll actually hear about in labs and clinics.

Health note (not medical advice): rhythms vary by age, health, and work schedule; if you suspect a sleep or endocrine disorder, seek personalized care.

1. Melatonin: the brain’s nightly “darkness” signal

Melatonin is the hormone that tells the body “it’s biological night.” The SCN relays darkness to the pineal gland via sympathetic pathways; the pineal then releases melatonin into blood and CSF, rising after dusk, peaking during habitual sleep, and falling toward morning. Light at night—especially in the hours before your usual bedtime—acutely suppresses melatonin, shifting sleep timing and altering body-clock signals to many organs. Clinically, timed melatonin can help shift circadian phase (e.g., after jet lag), but dosage and timing matter more than raw milligrams. Understanding melatonin’s nightly rise is foundational to the biology behind circadian rhythms because it marks internal night across tissues.

1.1 Why it matters

- Melatonin binds MT1/MT2 receptors in the SCN to promote sleepiness and stabilize circadian timing.

- Exposure history (bright evenings, dim days) changes amplitude and timing of the melatonin curve.

- Measurement via dim light melatonin onset (DLMO) is a gold-standard marker of circadian phase.

1.2 Numbers & guardrails (as of August 2025)

- Typical rise: ~2–3 hours before habitual sleep; peak in the biological night; suppressed rapidly by light.

- Assess phase with salivary/plasma melatonin; actigraphy and core temperature can complement.

Bottom line: Melatonin is the biochemical signature of darkness. To protect it, aim for bright days and dim evenings; use light strategically when you must shift schedule.

2. Cortisol: the morning mobilizer and daily metronome

Cortisol follows a robust diurnal rhythm: low in the first half of the night, rising before wake, then a rapid surge—the cortisol awakening response (CAR)—peaking ~30–45 minutes after you get out of bed. This morning pulse mobilizes glucose, sharpens attention, and helps “boot” immunity and metabolism for the day’s demands. Shift work, jet lag, chronic insomnia, and certain endocrine disorders can blunt or distort this curve, with downstream effects on energy, mood, and metabolic risk. For clinicians and researchers, the CAR is a reliable readout of circadian and HPA-axis function when sampled properly. PMC

2.1 Numbers & guardrails

- CAR magnitude commonly rises ~50% over the first 30–45 minutes post-awakening; expect individual variability.

- Peak cortisol usually occurs in the morning with a gradual decline across the day. PMC

- Night-shift schedules and jet lag can flatten or shift this rhythm. MDPI

2.2 Practical checks

- How to sample: collect saliva immediately on waking, +30, +45 minutes.

- Context matters: awakening time, light exposure, stress, and sleep restriction all modulate CAR—record them alongside samples.

Bottom line: Cortisol “opens the shop” for daytime physiology. A strong morning rise paired with low evening levels signals a resilient clock–HPA duet.

3. Adenosine: the homeostatic sleep-pressure meter

Adenosine is a neuromodulator that accumulates during wakefulness as cells expend ATP, binding brain A1 and A2A receptors to dampen arousal networks and increase sleep pressure. Unlike clock-driven hormones, adenosine encodes how long you’ve been awake, interacting with circadian signals to determine when sleep feels irresistible. Caffeine’s alerting effect comes from antagonizing adenosine receptors, temporarily masking sleepiness without “erasing” debt. As research expands (including 2023–2024 updates), adenosine is a chief bridge between metabolism and sleep drive.

3.1 Why it matters

- It explains why a late nap or heavy caffeine can delay sleep despite a normal circadian phase.

- Adenosine receptor signaling shapes transitions between wake, NREM, and REM sleep. ScienceDirect

3.2 Mini-checklist

- Time caffeine: stop 6–8 hours before target bedtime to reduce adenosine interference.

- Build pressure: anchor wake time; use daylight and activity to normalize build-up.

- Watch naps: keep them short (≤20–30 min) and early afternoon.

Bottom line: If melatonin marks “when it’s night,” adenosine marks “how tired you’ve earned.” Getting both aligned makes sleep happen on time.

4. Orexin (Hypocretin): the arousal stabilizer that keeps you awake on purpose

Orexin-A and -B (hypocretins) from the lateral hypothalamus provide a tonic “stay awake” drive and stabilize the boundary between sleep and wake. When this system fails—as in narcolepsy with cataplexy—people experience sudden sleep intrusions and unstable vigilance. Orexin neurons integrate circadian timing, energy status, and reward, projecting widely to brainstem and forebrain arousal hubs. Pharmacology has moved fast: dual orexin receptor antagonists (DORAs) now therapeutically release the brake at night to promote sleep, while orexin agonists are being explored to boost daytime alertness. Frontiers

4.1 How it interfaces with the clock

- Orexin output is highest during the active phase (day for diurnals, night for nocturnals) and is modulated by SCN-aligned cues.

- It cross-talks with monoamine systems (noradrenaline, histamine, dopamine) and basal forebrain circuits to maintain consolidated wakefulness.

4.2 Tools & examples

- Therapeutics: DORAs help insomnia by dampening orexin signaling at night; emerging agonists aim to treat hypersomnolence. ScienceDirect

- Case pattern: daytime sleepiness with vivid dreams, sleep paralysis, and cataplexy points to orexin deficiency—distinct from delayed sleep phase.

Bottom line: Orexin is the brain’s stability control for wakefulness—integrating circadian timing with motivation and metabolism to keep wake steady when it should be.

5. Serotonin: the light-gatekeeper tuning clock sensitivity

Serotonin (5-HT) fibers from the dorsal and median raphe nuclei project to the SCN, where they modulate how strongly light resets the clock. Rather than serving as the main “time” signal, serotonin tunes the pacemaker’s sensitivity—facilitating some glutamatergic light responses by day and damping them at night. This gating function helps prevent over-corrections to incidental light and connects mood circuitry to circadian alignment. Dysregulated serotonin can make the clock more fragile to late-night light, with downstream effects on sleep timing and mood. PubMed

5.1 Why it matters

- Photoperiod resilience: balanced 5-HT helps the SCN resist noise and respond only to meaningful light cues.

- Mood link: stress-serotonin interactions can disrupt rhythms and increase depression risk; aligning sleep–light patterns is part of care.

5.2 Evidence snapshots

- Electrical or pharmacologic manipulation of raphe 5-HT alters SCN phase shifting in animals. ScienceDirectPhysiology Journals

- Emerging work ties circadian nuclear receptors (e.g., REV-ERBα) in raphe 5-HT neurons to dusk-time behavior in mice. Nature

Bottom line: Serotonin doesn’t set the clock; it sets how settable the clock is—a crucial nuance when troubleshooting light timing, mood, or SSRI effects. Exploration Publishing

6. Dopamine: a motivator with its own local clocks

Dopamine modulates reward, movement, and retinal light processing—and it shows circadian patterns shaped by both SCN signals and local molecular clocks. In the retina, dopamine interacts with melanopsin pathways to influence photoentrainment. In midbrain circuits, recent work suggests dopaminergic neurons have intrinsic clock machinery that gates firing patterns across the day, linking motivation, learning, and motor output to time-of-day states. Clinically, dopaminergic rhythm disruption is being explored as one contributor to sleep and circadian symptoms in Parkinson’s disease and other conditions.

6.1 Tools/Examples

- Retinal clock: dopamine modulates melanopsin-dependent retinal waves and light responses during development.

- Behavioral timing: time-of-day variation in dopamine neuron bursting may shape motivation and motor readiness. Nature

6.2 Practical implications

- Evening bright light might have different behavioral effects than morning light in dopaminergic circuits; align light with desired alertness and mood targets.

Bottom line: Dopamine sits at the intersection of “wanting,” movement, and circadian timing—making daily rhythm a variable to consider in both experiments and therapy. Frontiers

7. GABA–Glutamate Balance in the SCN: how an “inhibitory” clock talks in stereo

Most SCN neurons release GABA, long puzzling scientists: how can an inhibitory network keep itself active and precise? The answer is dynamic balance. Across the day, GABA’s effects can switch between inhibitory and excitatory depending on intracellular chloride and astrocyte regulation of extracellular GABA levels. Meanwhile, glutamate from retinal inputs delivers light information to the SCN’s core. The shifting interplay lets the SCN encode time robustly and adjust to dawn/dusk without losing synchrony. This balance is central to how neurotransmitters—not only hormones—implement the body’s timing plan. PMC

7.1 Why it matters

- Intercellular GABA signaling is essential for coherent behavioral rhythms; disrupting it desynchronizes the network.

- Excitatory/inhibitory GABA actions vary with time of day and micro-region within the SCN.

7.2 Mini-checklist

- Protect day–night contrast: prioritize strong daytime light and dark, quiet nights; the SCN uses these to tune GABA/glutamate coupling.

- In experiments: note photoperiod and recording time—GABA polarity and coupling can flip with context. PubMed

Bottom line: The SCN’s language is GABA modulated by glutamate—and even its “inhibition” has time-of-day dialects that keep the clock accurate.

8. VIP and AVP: the SCN’s peptides that synchronize the network

Within the SCN, neurons use two key peptides—vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and arginine vasopressin (AVP)—to synchronize cellular clocks. VIP neurons in the SCN core help align cells to external light via VPAC2 receptors; AVP neurons in the shell convey phase information and contribute to downstream endocrine timing. When VIP signaling is impaired, single neurons may still tick, but population rhythms lose coherence; restoring rhythmic VIP release re-establishes synchrony. AVP supports coupling and output rhythms, helping translate SCN time into daily patterns in body temperature, hormone secretion, and behavior.

8.1 Tools/Examples

- Slice studies: excessive exogenous VIP can paradoxically reduce synchrony—timing and dose are critical.

- Developmental notes: VIP is vital for neonatal SCN synchrony; AVP contributes to network maturation and robustness. PubMed

8.2 Why it matters outside the lab

- These peptides explain why bright days and dim nights matter: light entrains VIP-rich core neurons, which then phase-align the whole SCN to keep your schedule steady.

Bottom line: VIP sets the beat; AVP keeps the band together—together ensuring the master clock’s cells play in time.

9. Metabolic Hormones (Insulin, Leptin, Ghrelin): bridging clocks and nutrition

Peripheral hormones knit metabolism into circadian time. Insulin sensitivity oscillates across the day in muscle and adipose; misaligned schedules and late-night eating can worsen glucose handling. Leptin (satiety) and ghrelin (hunger) also show daily rhythms and respond to sleep restriction and circadian misalignment—tilting appetite toward higher-energy foods when we’re off-schedule. The SCN coordinates these signals with feeding/fasting cycles and tissue clocks; in turn, meals act as “zeitgebers” for peripheral clocks. Practically, timed meals and consistent sleep–wake patterns can improve appetite control and metabolic markers.

9.1 Numbers & guardrails (as of August 2025)

- Human studies show circadian misalignment lowers insulin sensitivity independent of total sleep.

- Appetite hormones shift unfavorably (↑ghrelin, ↓leptin) with insufficient sleep and misaligned schedules.

9.2 How to apply

- Anchor meals: keep a consistent daytime eating window; avoid large meals 2–3 hours before bed.

- Time the zeitgebers: morning light + daytime activity + regular meals help re-align clocks after travel or shift changes.

- Clinical lens: in diabetes risk, address schedule regularity alongside calories and macros.

Bottom line: Your metabolism keeps time. Align sleep, light, and meals to move insulin, leptin, and ghrelin in your favor.

FAQs

1) What exactly is the SCN and how does it “see” light?

The suprachiasmatic nucleus is a ~20,000-neuron cluster in the hypothalamus. Specialized retinal ganglion cells send light information directly to it via the retinohypothalamic tract. From there, the SCN times neural and hormonal outputs to organs. Morning light is the dominant daily reset cue. NIGMSPMC

2) How are circadian rhythms measured in people?

Researchers and clinicians use dim light melatonin onset (DLMO), core body temperature minima, salivary cortisol (including the awakening response), actigraphy, and sleep logs. Each marker reveals a different piece of the timing puzzle and is chosen based on the question at hand.

3) Is melatonin a sleep hormone or a clock hormone?

Both—but primarily a clock signal of biological night. It nudges sleep–wake timing via MT1/MT2 receptors and feeds back to the SCN, while also having modest direct sleep-promoting effects. Light timing exerts stronger control than supplement dose.

4) What is the cortisol awakening response (CAR) and why does it matter?

CAR is a ~30–45-minute post-wake cortisol surge that prepares the body for daytime. It’s a sensitive marker for schedule alignment, stress load, and HPA-axis function; sampling protocols must tightly control timing and light. PMC

5) Does caffeine “fix” sleepiness?

Caffeine blocks adenosine receptors, masking sleep pressure temporarily. It does not repay sleep debt or correct circadian phase, and late-day use can delay bedtime. Strategic timing and dose help preserve nighttime sleep.

6) Are evening blue-light filters enough to protect melatonin?

They help but aren’t perfect. Intensity, spectrum, and timing all matter; reducing overall brightness and screen time in the last 2–3 hours before bed provides stronger protection than filters alone.

7) How do meal times reset peripheral clocks?

Liver, muscle, adipose, and gut clocks respond to feeding–fasting cycles. Regular daytime meals act as zeitgebers, improving synchrony with the SCN and supporting glucose control; erratic late eating pushes clocks out of phase. PMC

8) What’s the role of peptides like VIP and AVP inside the SCN?

They synchronize cellular oscillators so the SCN outputs a clean, high-amplitude rhythm. VIP is crucial for coupling and light-entrainment; AVP helps stabilize phase relationships and carry timing to downstream hypothalamic targets. PMC

9) Can circadian disruption contribute to mood disorders?

Yes. Misalignment alters serotonin and dopamine pathways and destabilizes sleep, which can worsen or predispose to depression and anxiety. Aligning light exposure, sleep schedule, and social/meal timing is part of comprehensive management. NatureScienceDirect

10) How quickly can I shift my clock after travel?

As a rule of thumb, 1–1.5 time zones per day with correctly timed light and meals. Morning light advances the clock; evening light delays it. Melatonin can aid phase shifts when timed relative to your destination DLMO.

Conclusion

The body keeps time through an elegant conversation between the brain’s master clock and a network of hormones and neurotransmitters. Melatonin and cortisol mark biological night and day; adenosine tallies wake time; orexin stabilizes wake; serotonin adjusts the clock’s sensitivity to light; dopamine shapes motivated behavior on a timetable; GABA and glutamate coordinate the SCN’s internal code; VIP and AVP synchronize the clock’s cells; and peripheral hormones like insulin, leptin, and ghrelin ensure that sleep, feeding, and metabolism are on the same page. When these signals are in sync, sleep feels natural, meals satisfy without fog, and energy flows predictably. When they’re not, everything feels harder. Your leverage points are simple but powerful: get bright morning light, dim evenings, regular sleep and meals, and consistent activity—then add targeted tools (including clinical ones) as needed. Start with today’s sunrise and tonight’s dim-down; the chemistry will follow.

Call to action: Pick one lever—morning light, earlier dinner, or dimmer evenings—and keep it consistent for 7 days to feel your internal clock click into place.

References

- Circadian Rhythms — National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), May 20, 2025. NIGMS

- Reddy S. Physiology, Circadian Rhythm — StatPearls, updated 2023. NCBI

- Arendt J. Physiology of the Pineal Gland and Melatonin — Endotext/NCBI Bookshelf, 2022. NCBI

- Savage RA et al. Melatonin — StatPearls, 2024. NCBI

- Bowles NP et al. The circadian system modulates the cortisol awakening response — Frontiers in Neuroscience, 2022. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins.2022.995452/full Frontiers

- Okun ML et al. What constitutes too long of a delay? Determining sampling criteria for the cortisol awakening response — Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2010 (methods cited from 2009 preprint). ScienceDirect

- Ma WX et al. Adenosine and P1 receptors: Key targets in the regulation of sleep-wake, torpor and hibernation-like states — Frontiers in Pharmacology, 2023. Frontiers

- Jászberényi M et al. The Orexin/Hypocretin System, the Peptidergic Regulator of Arousal and Sleep — Biomedicines, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10886661/ PMC

- Kinane C et al. Dopamine modulates the retinal clock through melanopsin-dependent regulation of acetylcholine retinal waves — BMC Biology, 2023. BioMed Central

- Klett N et al. GABAergic signalling in the suprachiasmatic nucleus is required for circadian behavioural rhythmicity — 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC11612841/ PMC

- Patton AP et al. Astrocytic control of extracellular GABA drives circadian timekeeping in the SCN — 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10214171/ PMC

- Ono D et al. Roles of Neuropeptides, VIP and AVP, in the Mammalian Central Clock — Frontiers in Neuroscience, 2021. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins.2021.650154/full Frontiers

- Chaput J-P et al. The role of insufficient sleep and circadian misalignment in obesity — Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 2023. Nature

- Catalano F et al. Circadian Clock Desynchronization and Insulin Resistance — Nutrients, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9819930/ PMC

- Her TK et al. Circadian Disruption across Lifespan Impairs Glucose Metabolism — Cells, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10892663/ PMC