A good nap doesn’t just “rest your eyes”—it triggers rapid, measurable brain changes that restore alertness, sharpen learning, and steady emotions. In as little as 10–30 minutes, your brain can shift into light non-REM sleep and, if you sleep longer, dip into slow-wave sleep (and sometimes REM), launching the cellular, electrical, and chemical processes that reset attention and consolidate memories. In brief: during a well-timed nap, adenosine-driven sleep pressure eases, sleep spindles and slow waves coordinate hippocampus-to-cortex “replay,” the autonomic nervous system tilts parasympathetic, and—if REM appears—associative networks open the door to creative insight. This guide is educational and does not replace medical advice; if you have a sleep disorder or excessive daytime sleepiness, consult a clinician.

Snapshot definition: A nap is a short sleep episode (typically 10–90 minutes) that partially reproduces night-sleep architecture. Short naps mainly deliver Stage N1/N2 with spindles; longer naps can add slow-wave sleep and REM, each linked to distinct brain benefits.

1. Your Brain Eases “Sleep Pressure” by Clearing Adenosine

Adenosine—the metabolic by-product of cellular energy use—accumulates during wakefulness and increases homeostatic sleep pressure. When you nap, adenosine signaling falls and arousal systems recalibrate, which is why even a brief nap can relieve fatigue and brighten attention. Mechanistically, adenosine acts via A1 and A2A receptors across basal forebrain, hypothalamus, and other hubs that govern sleep–wake control; blocking these receptors (as caffeine does) temporarily reduces perceived sleepiness without addressing underlying need. In practice, naps reduce subjective sleep pressure directly; “coffee naps” stack receptor blockade on top of that clearance for an extra punch. These dynamics also partly explain why late, long naps can make bedtime harder: you’ve removed too much pressure too close to night.

1.1 Why it matters

- Faster alertness recovery: Lower adenosine signaling reduces the “need to sleep,” so attention systems come back online quickly.

- Circadian cross-talk: Adenosine also modulates the circadian clock’s light sensitivity, so naps that manage adenosine well pair better with your afternoon dip.

- Smarter caffeine use: Caffeine is most effective when adenosine is high; a short nap can synergize by lowering it just as caffeine kicks in (~20 minutes).

1.2 Numbers & guardrails

- Short naps (10–20 min): Quick adenosine relief with minimal grogginess.

- Longer naps (30–60+ min): Deeper pressure relief but higher risk of sleep inertia right after waking.

- Timing: Earlier afternoon aligns with the circadian dip and minimizes bedtime interference.

Bottom line: naps work partly because they reduce adenosine-driven sleep pressure; time them early and keep them short on workdays. Sleep Foundation

2. Memory “Replays” from Hippocampus to Cortex During Naps

Naps re-stage the memory-consolidation choreography your brain runs at night. In light non-REM sleep, bursts of sleep spindles (brief 12–15 Hz oscillations) and slow waves coordinate hippocampal “replay” of recent experiences, strengthening synapses and transferring traces to neocortex. Experiments that tag new memories with odor or sounds and then re-present those cues during a nap show better recall later, direct evidence that reactivation during sleep stabilizes memory. Longer naps (60–90 minutes) that include slow-wave sleep (and sometimes REM) can match a night’s memory gains for specific tasks, especially perceptual and associative learning.

2.1 How it works

- Spindle–slow-wave coupling: Slow waves group spindles, which time hippocampal–cortical communication for plasticity.

- Targeted memory reactivation (TMR): Learned cues presented quietly during a nap bias replay toward those memories.

- Reward tagging: The brain may preferentially replay information tied to reward or relevance.

2.2 Mini-checklist for learning days

- Study → nap 20–90 minutes → brief review.

- If possible, use a neutral cue during learning (e.g., a particular scent) and keep it present during the nap at very low intensity.

- Avoid loud cues; arousals disrupt consolidation.

Nap takeaway: spindles and slow waves during naps help move fragile, hippocampal memories toward more durable cortical storage.

3. Attention and Learning “Refresh” via Sleep Spindles and Prefrontal Networks

Your ability to take in new information fades across the day—then rebounds after a nap. Mechanistically, sleep spindles during a mid-afternoon nap predict post-nap learning capacity, likely by resetting synaptic efficiency and prefrontal-hippocampal communication. Imaging studies show that after napping, prefrontal regions linked to executive attention perform better on encoding tasks, while reaction times and vigilance improve. This refresh is most evident when the nap ends in Stage N2; deeper slow-wave sleep adds benefits for consolidation but raises the risk of sleep inertia right after waking.

3.1 Why it matters

- Sharper encoding window: Spindle-rich naps restore the “bandwidth” to take in new facts.

- Better vigilance: Even 10–20 minutes can improve attention for 1–3 hours, critical for shift work and safety.

- Evening classes? A nap beforehand can lift study efficiency.

3.2 Practical guardrails

- Length: 10–30 minutes when you need to get back to work quickly; 60–90 minutes if you can afford grogginess for deeper gains.

- Wake strategy: Bright light, brisk walk, or cool water to shorten inertia.

- Schedule: Aim for the circadian dip (roughly 1–3 p.m. local).

In short: spindles are the nap’s secret sauce for restoring learning capacity and attention—especially in the early afternoon. Berkeley News

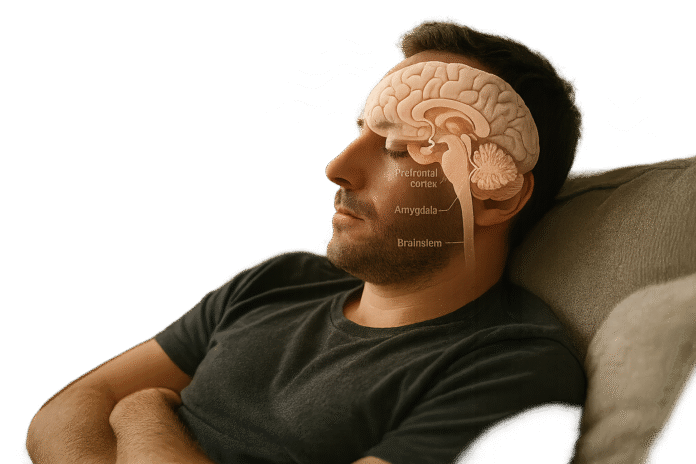

4. Emotions Recalibrate: The Amygdala–Prefrontal Balance Resets

Sleep loss makes the emotional brain reactive; sleep restores control. After inadequate sleep, the amygdala over-responds to negative stimuli while top-down regulation from the prefrontal cortex weakens. Naps can partially reverse this pattern: even a 30-minute nap after sleep restriction has been shown to restore prefrontal activation and reduce interference from default-mode regions during tasks that demand inhibitory control. While a single nap won’t cure mood disorders, its acute rebalancing of limbic–prefrontal circuits can steady mood and improve impulse control for the rest of the day.

4.1 Numbers & guardrails

- Sleep-deprived? If you’re short on sleep, a 60–90 minute nap may be worth the longer inertia because emotion regulation improves alongside attention.

- Everyday stress? 15–30 minutes often suffices for a calmer, clearer afternoon.

4.2 Common mistakes

- Napping too late: Pushing past 4 p.m. can disturb bedtime, especially for sensitive sleepers.

- Expecting therapy-level effects: Naps help; they don’t replace treatment for anxiety, depression, PTSD, or insomnia.

Core idea: by easing limbic over-activity and restoring prefrontal control, a nap helps you respond—not react—to the rest of your day. PubMedPMCDove Medical Press

5. Creativity and Insight Rise (Especially When REM Appears)

Sleep doesn’t just store facts—it restructures them. Studies show that sleep can more than double the chance you’ll discover a hidden rule or see a problem from a fresh angle, a hallmark of insight. Shorter naps that contain only non-REM can still aid flexible thinking, but longer naps that reach REM seem to unlock more associative, “far-flung” connections, supporting idea recombination and creative problem-solving. Practically, that’s why a 60–90 minute nap before a brainstorming session can feel like a mental palette cleanser.

5.1 How to use naps for insight

- Prime the problem: Work on it for 20–30 minutes pre-nap.

- Nap 60–90 minutes when possible to increase odds of REM.

- Debrief on waking: Jot dream fragments or odd associations; they can contain useful jumps.

5.2 Mini case

A coder stumped by a sorting bug reviews unit tests, naps 80 minutes, wakes with the notion to re-key by a secondary index—a simple, non-obvious fix often missed while “trying harder.”

Takeaway: when your goal is insight rather than speed, a longer nap that includes REM can catalyze the mental reframing you need. Walker Lab

6. Motor Skills and Procedural Learning Get a Boost

From piano scales to surgical sutures, procedural memory strengthens after sleep—and naps can deliver that boost. Daytime naps have been shown to improve motor memory consolidation, with performance gains tied less to total minutes asleep and more to specific features (e.g., spindle density, slow-wave power). If your work or sport depends on precision timing and sequence learning, scheduling a training block followed by a nap can yield measurable performance benefits at retest.

6.1 Tools/Examples

- After practice: 30–90 minute nap within 2–3 hours of training.

- Track progress: Retest the same sequence later that day; log accuracy and speed.

- Wearables: If you use EEG-capable headbands, watch for spindle counts; they often correlate with consolidation.

6.2 Common pitfalls

- All wake, no rest: Cramming practice without recovery impairs plasticity.

- Assuming longer is always better: Gains depend on architecture, not only duration.

Bottom line: for skills built with repetition, naps speed consolidation so the next practice round starts from a higher baseline.

7. Stress Systems Downshift: Parasympathetic Tone and HRV Improve

During non-REM sleep, the autonomic nervous system tilts toward the parasympathetic branch. In naps, this shows up as higher high-frequency heart rate variability (HF-HRV) and lower LF/HF ratios—physiological signs of stress down-regulation. Longer naps that include both slow-wave sleep and REM can produce cardiovascular profiles similar to nocturnal sleep, while short naps still nudge HRV upward and reduce subjective fatigue. For knowledge workers, that translates into steadier focus; for athletes, faster recovery between sessions.

7.1 Numbers & guardrails

- HRV changes: Expect modest improvements after 20–30 minutes; more robust shifts after 60–90 minutes.

- When to wake: If you need to perform immediately, keep it short to avoid inertia.

7.2 Mini-checklist

- Dim room, cool temperature.

- Eye mask or blackout curtains.

- Gentle alarm; stand and hydrate on waking.

Takeaway: by engaging parasympathetic pathways and improving HRV, naps don’t just clear your head—they also ease the body’s stress load.

8. Cleanup and Housekeeping: CSF Flow and the Glymphatic System

Sleep supports “brain housekeeping”—the circulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) through perivascular channels (the glymphatic system) that helps remove metabolic waste. Human imaging shows CSF flow increases during non-REM sleep and drops sharply during REM; animal and human data suggest this clearance is most efficient in deeper sleep, but shorter naps may still contribute if they include consolidated non-REM. While the field continues to evolve, aligning naps with your natural circadian dip and limiting duration helps you sample this non-REM window without harming nighttime sleep.

8.1 Numbers & guardrails

- Non-REM emphasis: Short, early-afternoon naps are more likely to be N2-heavy.

- Long naps: Useful for recovery but don’t overuse; prioritize consistent 7+ hours at night.

8.2 Why it matters

- Metabolic maintenance: Efficient waste clearance is tied to long-term brain health.

- Research note: Evidence in humans is growing; effects likely scale with depth and continuity of non-REM.

In essence: naps aren’t a full wash cycle, but they can contribute to the day’s cleanup—especially if they capture non-REM sleep.

9. Timing and Architecture: Why Mid-Afternoon Naps Work Best

Most people feel a natural post-lunch dip in alertness—even without eating lunch—due to circadian dynamics. Napping during this window (roughly 1–3 p.m.) aligns with biology and reduces the risk of delaying bedtime. Short naps (10–20 minutes) deliver quick alertness with minimal inertia; 30–60 minutes add slow-wave sleep (great for consolidation) but can produce grogginess that fades within ~30 minutes; 90 minutes can include a full cycle with REM, useful for creativity or heavy recovery. Meta-analyses and trials show that even very brief naps improve mood and vigilance for hours afterward.

9.1 Numbers & guardrails (as of August 2025)

- 10–20 minutes: Best for fast alertness; minimal inertia.

- 30–60 minutes: Deeper gains; plan a 15–30 minute buffer on waking.

- ~90 minutes: Full cycle; reserve for days you can afford a slow ramp.

- Tip: If you enjoy them, coffee naps (caffeine immediately pre-nap) can boost post-nap alertness when you wake.

- Night sleep first: Adults still need 7+ hours at night for health.

9.2 Mini checklist

- Nap earlier rather than late; keep it planned and consistent.

- Use light, movement, and hydration to clear inertia.

- Track personal response; adjust length to your tasks.

Bottom line: the right nap at the right time leverages your circadian dip and the brain’s sleep architecture to deliver the benefits you want—without derailing your night.

FAQs

1) How long should I nap for brain benefits?

For quick alertness with minimal grogginess, 10–20 minutes is a reliable target. If you need deeper learning or recovery, 30–60 minutes engages slow-wave processes but may cause 15–30 minutes of sleep inertia after waking. A full-cycle ~90-minute nap can include REM for creative problem-solving—use it when timing allows and bedtime won’t be affected.

2) When is the best time to nap?

Early afternoon (about 1–3 p.m.) aligns with the circadian post-lunch dip, so you fall asleep more easily and are less likely to delay nighttime sleep. Shift workers can place strategic naps before or during work bouts; the principle is the same—pair naps with dips in alertness, not close to intended bedtime.

3) Do naps really improve memory, or is that hype?

Yes. Naps trigger spindle-slow-wave dynamics that stabilize memories and, with targeted cues (sound/odor), can selectively strengthen recently learned material. Longer naps (60–90 minutes) that include slow-wave sleep can match a night’s gains for certain tasks such as perceptual learning.

4) Why do I feel groggy after some naps?

That “thick-headed” state is sleep inertia, stronger if you wake from slow-wave sleep. It usually resolves within ~30 minutes. Keep naps to 10–20 minutes when you must perform immediately, or build a buffer after 30–60-minute naps. Light, movement, and cool water help.

5) Are coffee naps legit?

They can be. Caffeine blocks adenosine receptors while a short nap reduces adenosine itself; the combination often boosts alertness more than either alone if you keep the nap to ~20 minutes so caffeine peaks as you wake. Avoid late-day use if caffeine disrupts your night.

6) Will regular napping hurt my nighttime sleep?

Short, early-afternoon naps rarely harm healthy nighttime sleep. Long or late naps can remove too much sleep pressure and push bedtime later. If you struggle with insomnia, prioritize a consistent night schedule and use brief daytime rest sparingly while you address the root causes. Mayo Clinic

7) Can naps protect brain health long-term?

Emerging evidence suggests habitual daytime napping is associated with larger total brain volume—a marker linked to healthy aging—though effects on cognition vary and causality is still being explored. Naps are a tool, not a cure-all; nightly sleep remains foundational. Sleep Health Journal

8) Do naps help athletes and musicians with motor skills?

Yes. Procedural learning benefits from sleep; naps after practice consolidate timing and sequence patterns so you return sharper. Gains track with sleep features (e.g., spindle density) as much as duration, so quality matters. PubMed

9) Are naps good for creativity?

They can be, especially if they include REM. Studies show sleep more than doubles the chance of discovering hidden rules and supports looser, associative thinking—use longer naps when you need fresh angles. Nature

10) How do naps affect stress physiology?

Naps nudge the autonomic nervous system toward parasympathetic dominance, reflected in higher HRV during non-REM sleep; people often feel calmer and more resilient afterward. Longer naps can approximate nocturnal cardiovascular benefits.

11) I can’t fall asleep—can a “quiet rest” still help?

Yes. Even 10–15 minutes of eyes-closed rest in a dark, quiet place can reduce mental load. But if rest alone isn’t cutting it regularly, experiment with consistent nap timing, wind-down routines, or a brisk 10-minute walk plus hydration before trying again.

12) Is a NASA-style 26-minute nap a thing?

The widely cited aviation research suggests a planned ~26-minute cockpit nap improved alertness and performance in pilots. Consider it a practical template for safety-critical work: short, scheduled, and earlier than end-of-shift.

Conclusion

A nap is not a tiny copy of night sleep—it’s a precision tool. By easing adenosine-driven sleep pressure, coordinating hippocampal “replay” with spindles and slow waves, tilting the autonomic system toward recovery, and occasionally tapping REM’s associative power, a well-timed nap can transform the second half of your day. The key is to match length and timing to your goal: 10–20 minutes for fast alertness; 30–60 minutes when consolidation matters and you can absorb a little inertia; ~90 minutes when you’re chasing creativity or deep recovery and bedtime isn’t at risk. Keep naps early, keep them planned, and treat them as part of a larger sleep strategy anchored by 7+ hours at night. Done thoughtfully, napping becomes a repeatable, low-cost way to learn better, think clearer, feel steadier—and work and live a bit more like your best self.

CTA: Pick tomorrow’s nap window now—set a 20-minute alarm for early afternoon and notice how your brain handles the rest of the day.

References

- Mednick S, Nakayama K, Stickgold R. “Sleep-dependent learning: a nap is as good as a night.” Nature Neuroscience. 2003. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12819785/

- Rasch B, Büchel C, Gais S, Born J. “Odor cues during slow-wave sleep prompt declarative memory consolidation.” Science/PubMed. 2007. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17347444/

- Cowan E et al. “Sleep Spindles Promote the Restructuring of Memory Representations in Humans.” Journal of Neuroscience. 2020. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7046449/

- Leong RLF et al. “Influence of mid-afternoon nap duration and sleep inertia on cognition and mood.” Sleep Medicine. 2023. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10091091/

- Dutheil F et al. “Effects of a Short Daytime Nap on Cognitive Performance.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8507757/

- Cellini N et al. “Heart rate variability during daytime naps in healthy adults.” Psychophysiology. 2016. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26669510/

- Whitehurst LN et al. “Comparing the cardiac autonomic activity profile of daytime naps and nocturnal sleep.” Physiology & Behavior. 2018. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2451994417300172

- Ungurean G et al. “Wide-spread brain activation and reduced CSF flow during REM sleep.” Nature Communications. 2023. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-38669-1

- Reddy OC, Van der Werf YD. “The Sleeping Brain: Harnessing the Power of the Glymphatic System.” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2020. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7698404/

- Reichert CF, Deboer T. “Adenosine, caffeine, and sleep–wake regulation.” Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2022. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9541543/

- Monk TH. “The post-lunch dip in performance.” Chronobiology International. 2005. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15892914/

- Paz V et al. “Is there an association between daytime napping, cognitive function and brain volume? A Mendelian randomisation study in the UK Biobank.” Sleep Health. 2023. https://www.sleephealthjournal.org/article/S2352-7218(23)00089-X/fulltext

- Yoo SS et al. “The human emotional brain without sleep—a prefrontal amygdala disconnect.” Current Biology. 2007. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982207017836

- Sleep Foundation. “NASA Nap: How to Power Nap Like an Astronaut.” 2023. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/sleep-hygiene/nasa-nap