If you’re struggling to stay on task, the right structure can flip your workday from scattered to surgical. Below you’ll find 12 evidence-informed focus methods—starting with the Pomodoro Technique—that help you protect attention, reduce switching costs, and make visible progress without burning out. This guide is for knowledge workers, students, creators, and anyone who needs to do thinking work in a noisy world. Quick note: nothing here is medical advice; if you’re managing conditions like ADHD, talk to a clinician about what’s right for you.

Quick definition: The Pomodoro Technique is a cycle of ~25 minutes of focused work followed by a ~5-minute break, with a longer break after four cycles. More broadly, a focus method is any structured approach that schedules intense attention and intentional rest to boost output and reduce mental fatigue.

Fast start (5 steps): Define one concrete task → set a timer for 25–50 minutes → silence notifications and close extras → work until the timer ends → take a short break and log what moved.

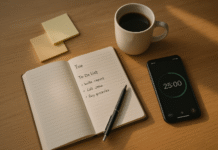

1. The Pomodoro Technique

The Pomodoro Technique boosts momentum by turning work into short, winnable sprints. Start with a target task, set a 25-minute timer, and commit to zero context switching until the bell. Then take a 5-minute break. After four cycles, rest for 15–30 minutes. This rhythm reduces the “I’ll just check…” impulse, gives your brain recovery time, and creates a cadence that’s forgiving when tasks are ambiguous. It shines for writing, coding, studying, and processing “heavy but bite-sized” work. If a task doesn’t fit in a single sprint, you’ll naturally break it down, which lowers friction. On days when energy is low, Pomodoro’s small wins rebuild confidence; on high-energy days, stacking cycles compounds progress.

1.1 How to do it

- Choose one meaningful task; define “done” for the next 25 minutes.

- Set a 25-minute timer; full-screen your work; enable Do Not Disturb.

- If interrupted, note it and return instantly; if unavoidable, pause and restart the sprint.

- Break for 5 minutes: stand, hydrate, avoid screens.

- After 4 cycles, take a 15–30-minute long break.

1.2 Numbers & guardrails

- Classic cadence: 25/5, long break after 4 cycles (≈2 hours total).

- Variants: 35/7 or 50/10 for deeper tasks; keep breaks true breaks.

- “Overflow rule”: if you finish early, review and polish; if you’re mid-flow at 25, jot a marker and stop—protect the rhythm.

1.3 Tools/Examples

Analog timer (loud tick helps some), Focus To-Do, Be Focused, Forest, or a simple phone timer in airplane mode.

Mini case: Four 25/5 cycles often move a draft from outline to 1,000–1,500 words while staying fresh. Over a 6-hour window, 8–10 sprints routinely ship a solid first draft.

Why it works: It creates dynamic urgency plus scheduled recovery; Francesco Cirillo’s original method formalized this into repeatable cycles.

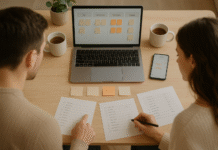

2. Timeboxing on Your Calendar

Timeboxing assigns fixed calendar blocks to specific tasks so your to-dos live in time, not limbo. The direct answer: decide what you’ll do and when, then protect that block like a meeting with yourself. Unlike open-ended lists that invite procrastination, timeboxing converts intent into a visible commitment. It also reduces decision fatigue because your plan for the next hours is already on the calendar. The method scales across roles: solo contributors reserve build time, managers cluster meetings and defend maker-time, and students map study blocks before deadlines.

2.1 How to do it

- Move top tasks from your list into calendar blocks with starts/finishes.

- Keep blocks realistic (30–120 minutes) and outcome-labeled: “Draft proposal section 2,” not “Work on proposal.”

- Batch admin blocks together; cluster meetings to protect long focus stretches.

- Treat blocks as appointments; if interrupted, reschedule, don’t delete.

- End each day by roughing in tomorrow’s boxes.

2.2 Common mistakes

- Overpacking without buffers; not naming outcomes; treating blocks as “nice to have.”

- Letting every invite pierce your plan; and failing to reschedule pushed work.

2.3 Why it works

Timeboxing has become a widely recommended way to reduce procrastination and improve follow-through by merging to-do lists with calendars. Harvard Business Review summarizes the core: decide what to do and when, then focus on that one thing during the box.

3. Time Blocking for Deep Work

Time blocking is the discipline of giving every minute a job, with explicit deep work blocks for cognitively demanding tasks. The direct answer: schedule 60–120-minute blocks for work that creates disproportionate value, then batch shallow tasks elsewhere. This approach is especially effective for research, design, writing, and complex problem-solving. You’ll miss occasionally; that’s expected—rewrite your blocks when reality changes. Over a week, time blocking makes the actual trade-offs of your commitments visible.

3.1 How to do it

- Pick 1–3 deep outputs for the day; assign 1–2 uninterrupted blocks for each.

- Pre-decide inputs (papers, data, briefs) to avoid scavenger hunts inside the block.

- Use a capture pad for stray thoughts; process it after.

- Track deep hours; aim for 2–4 per day on average.

3.2 Numbers & guardrails

- Start with one 60–90-minute block if your calendar is crowded.

- Expect to rewrite blocks once or twice a day as reality shifts.

- “Fence rule”: no Slack/email in deep blocks; use “office hours” elsewhere.

Why it works: Cal Newport’s long-running practice and writing popularized scheduling every minute and defending deep work with clear rituals; the method’s value is in the practice, not perfection.

4. Task Batching (Email, Admin, and Repetitive Work)

Task batching groups similar tasks so you switch contexts less and finish them faster. The direct answer: process email, messages, approvals, and small admin in 1–3 batches daily instead of sprinkling them between deep tasks. Batching reduces warm-up costs, keeps complex work uninterrupted, and helps you hit inbox zero without letting it eat your morning. It also pairs well with meeting clusters so you protect long creative blocks elsewhere.

4.1 How to do it

- Pick 2–3 times a day for email/messages (e.g., 10:30, 14:30, 16:45).

- Make checklists for routine admin (expenses, approvals, HR).

- Use templates/snippets for common replies; defer or delegate decisively.

4.2 Numbers & guardrails

- 20–40 minute batches are typical; extend during peak cycles, shrink otherwise.

- If your role demands responsiveness, set status expectations (e.g., “Replies by 3 pm”).

Evidence snapshot: Checking email less frequently reduces stress and improves well-being in field studies; batching communications is a practical way to implement that finding.

5. Single-Tasking (Stop Multitasking)

Single-tasking is the commitment to do one cognitively demanding thing at a time. The direct answer: resist juggling; switching between tasks adds measurable “switching costs” that slow you down and increase errors. By finishing steps sequentially, you protect working memory and reduce the friction of re-loading context. For most knowledge work, mono-tasking is the default you return to after every planned interruption.

5.1 Why it matters

- Psychological research has long shown that task switching carries a performance penalty; the APA summarizes decades of work on “switching costs” and why multitasking is inefficient for complex tasks.

- Field studies also find it can take around 23 minutes to fully resume a task after an interruption, which compounds across a day. MicrosoftGallup.com

5.2 Mini-checklist

- Close extra tabs; full-screen the current artifact.

- Park “quick wins” (see the Two-Minute Rule below) into a specific later block.

- Keep a capture pad for intrusive thoughts; process it at break time.

Bottom line: Single-tasking is the quiet superpower behind most other methods; treat it as your default mode and measure days by finished chunks, not started ones.

6. 90-Minute Ultradian Sprints (Use With Caution)

Ultradian rhythms are ~90-minute cycles observed in sleep and proposed during wakefulness; some practitioners match work bouts to this cadence. The direct answer: if you notice your energy naturally crests every 80–100 minutes, try scheduling 75–90-minute sprints with 10–20-minute breaks. This can feel more natural than shorter Pomodoro cycles for deep work like writing, analysis, and design. Important: evidence for a rigid 90-minute rule during wakefulness is mixed; treat this as a heuristic, not a law.

6.1 How to do it

- Plan one 75–90-minute “ultra sprint” in the morning when alertness is higher; add a second if capacity allows.

- Keep breaks longer (10–20 minutes); step away, hydrate, move, or take a brief walk.

6.2 Numbers & guardrails

- If you fade early, drop to 50–60 minutes; if you’re still rising at 90, stop anyway to protect the next sprint.

- Use a weekly reflection to note energy peaks; schedule sprints accordingly.

Evidence snapshot: Nathaniel Kleitman described the basic rest–activity cycle (BRAC) underlying sleep and suggested a wakeful analogue; later work debated the extent to which strict 90-minute cycles govern daytime performance—use it as a guide, not gospel.

7. The 52/17 Work–Break Ratio

The 52/17 method alternates ~52 minutes of focused work with ~17 minutes of rest. The direct answer: use this cadence if you find 25/5 too choppy and 90 minutes too long. It’s popular with teams who want a shared schedule that’s still humane. The longer break encourages genuine recovery—stand, stretch, refill water, and let your eyes and brain reset—so you return sharper.

7.1 How to do it

- Try two 52/17 cycles back-to-back for a solid morning; add a third in the afternoon.

- Use the first 5 minutes of each break to move; avoid doom-scrolling.

7.2 Mini case & note

- Teams often report higher sustained output and less late-day fatigue when adopting longer breaks.

- Origin: productivity-tracking company DeskTime reported this ratio from anonymized user data; it’s a descriptive finding, not a prescription—test and adapt.

Synthesis: 52/17 balances depth and recovery; if Pomodoro feels too “stop-start,” this is a strong middle path. Ensora Health

8. If–Then Planning (Implementation Intentions)

If–then planning turns vague intentions into specific trigger–action pairs, which increases follow-through. The direct answer: write “If it’s 9:00 and I’m at my desk, then I’ll start the Q3 analysis in my 90-minute block.” This reduces hesitation and makes starting automatic. Pair it with any method above: the if-clause binds to time (9:00), place (quiet room), or event (after stand-up), and the then-clause binds to the precise first action.

8.1 How to do it

- Identify a bottleneck behavior (e.g., starting a report).

- Create 2–3 if–then scripts that tie a cue to the first 2 minutes of the task.

- Put the scripts where you’ll see them (calendar notes, sticky, app).

- Review weekly; prune scripts you never use.

8.2 Numbers & guardrails

- Keep then-clauses concrete (“open dataset and run cell A1”).

- Use one script per situation; too many scripts dilute effect.

Evidence snapshot: Implementation intentions reliably improve goal attainment across domains in experiments and meta-analyses; the mechanism is making the cue–action link automatic so starting is frictionless.

9. Distraction Shield: Silence, Blockers, and Phone-Out-of-Sight

You can’t out-focus a stream of pings. The direct answer: silence non-urgent notifications, put your phone out of sight and reach, and use website/app blockers during deep blocks. Even mere notifications—without replying—can degrade performance; and simply having a smartphone on the desk can drain cognitive capacity. Pair this with calendar “focus time” so colleagues know you’re heads-down.

9.1 How to do it

- Enable Do Not Disturb during deep blocks; whitelist critical contacts.

- Use Freedom, Cold Turkey, or native Screen Time/App Limits for known rabbit holes.

- Place the phone in a drawer or another room for the block.

9.2 Numbers & guardrails

- Blockers: 45–120 minutes per session; schedule repeats.

- If your role requires availability, set visible status plus an emergency channel.

Evidence snapshot: Phone notifications themselves can impair attention; and the mere presence of your own smartphone reduces available cognitive capacity—so move it out of sight.

10. Specific Goals & Progress Tracking

Clarity beats willpower. The direct answer: set specific, challenging but realistic goals (e.g., “ship the 2-page brief by 4 pm”) and track progress visibly. Goal-specificity focuses attention; measuring progress sustains it. Use a daily “highlight,” a weekly scoreboard, or deep-work tallies to make momentum obvious. Combine with timeboxing so the goal has a time container.

10.1 How to do it

- Write today’s top 1–3 outcomes; phrase them as shipped artifacts.

- Define a numeric yardstick where possible (pages, tests, charts).

- Review progress at lunchtime; rewrite your afternoon boxes if needed.

10.2 Numbers & guardrails

- Targets should stretch but not break; recalibrate weekly.

- Tie each top goal to a calendar block or it won’t happen.

Evidence snapshot: Decades of research on goal setting theory shows that specific, challenging goals boost performance compared to vague “do your best” intentions; the effect is strongest with commitment and feedback.

11. Microbreaks & Nature for Attention Restoration

Short, intentional breaks restore directed attention. The direct answer: every 50–90 minutes, step away for 5–15 minutes; when possible, include greenery—a walk outside or even viewing natural scenes—to replenish mental resources. Microbreaks are not wasted time; they’re how you maintain quality in hour three. In open offices or small apartments, even looking out a window at trees or a quick loop around the block can help.

11.1 How to do it

- Pair breaks with movement: stretch, refill water, do 10 squats.

- Add a micro-dose of nature: balcony plant care, window views, a two-street walk.

- Avoid intense digital inputs (news, social) during breaks; protect the reset.

11.2 Numbers & guardrails

- 5–7 minutes for short cycles; 15–20 for long sprints.

- Cap phone use; choose light sensory input over cognitive heavy-lifting.

Evidence snapshot: Experiments show interacting with natural environments can improve performance on tasks requiring directed attention compared to urban settings—supporting attention restoration effects.

12. Shutdown Ritual & Next-Day Plan (Clear the Cognitive Cache)

End your day by closing loops and planning tomorrow; you’ll switch off faster and start stronger. The direct answer: spend 10–15 minutes wrapping up, capturing loose ends, scheduling the next day’s boxes, and then say a cue phrase (e.g., “Shutdown complete”). This reduces rumination about unfinished goals and shrinks “attention residue” that otherwise bleeds into your evening—and tomorrow’s focus.

12.1 How to do it

- Review inboxes briefly; capture any open loops to a trusted list.

- Sketch tomorrow’s top one to three outcomes and timeboxes.

- Visual cue: close tabs, tidy desk, write a one-line “next action” for your morning block.

- Verbal cue: a consistent phrase signals closure.

12.2 Numbers & guardrails

- 10–15 minutes is enough; protect it like any meeting.

- If urgent work pops up later, add it to tomorrow’s plan—but avoid re-opening everything.

Evidence snapshot: Research shows unfulfilled goals can occupy cognitive resources; making concrete plans frees up mental bandwidth. The shutdown ritual operationalizes that insight so you can truly disengage and return fresher.

FAQs

1) Is the Pomodoro Technique still effective in 2025?

Yes—because its value is structural, not trendy. Short sprints with guaranteed breaks reduce procrastination and keep energy steady. Many people now adapt the intervals (e.g., 35/7 or 50/10) to match task complexity. If 25 minutes feels too short for deep work, try 50/10 or 52/17 while preserving the work-then-rest cycle that prevents fatigue.

2) Pomodoro vs. timeboxing vs. time blocking—what’s the difference?

Pomodoro is a fixed sprint cadence (e.g., 25/5). Timeboxing schedules specific tasks directly onto your calendar with start and end times. Time blocking goes further: you plan your whole day in blocks (including deep work) and constantly rewrite the plan as reality shifts. They’re complementary—Pomodoro can live inside a timebox/time block.

3) What’s the “best” work/break ratio?

There isn’t a single winner. Use 25/5 for momentum and busy calendars; 50/10 or 52/17 when you want longer flow with real rest; 75–90/15–20 if your energy holds. Pick one, run it for a week, then adjust based on output quality and fatigue. The crucial part is intentional breaks to restore attention.

4) How many Pomodoro cycles should I aim for per day?

For knowledge work, 8–12 focused sprints across a full day is common (about 4–6 hours of true focus with breaks), depending on meetings and the heaviness of tasks. Track completions for two weeks, then set a realistic personal target with buffers for collaboration and life.

5) What if my job requires rapid responses?

Use a hybrid: calendar office hours (e.g., 11:30–12:00 and 16:00–16:30) for messages and approvals; batch non-urgent email into 2–3 windows; and schedule at least one defended deep block. Communicate your response SLAs so teammates know when you’ll get back. This preserves responsiveness without sacrificing your best attention.

6) Do website blockers and “Do Not Disturb” really help?

Yes. Lab studies show even passive notifications can degrade performance, and the mere presence of your phone can sap cognitive capacity. Put the phone away and block known rabbit holes during focus blocks; the combination materially improves attention.

7) How do meetings affect focus—and what can I do?

Meetings fragment attention. Research links fewer meetings and protected focus time with higher productivity and well-being. Cluster meetings, create “no-meeting” windows, and use tools like Viva Insights’ Focus Time to auto-block heads-down work on your calendar. MIT Sloan Management Review

8) Is multitasking really that bad?

For cognitively heavy tasks, yes: switching imposes measurable costs and increases errors. You may feel busy but ship less. The fix is simple, not easy: single-task by default, batch the small stuff, and give deep tasks their own timebox.

9) Do breaks with nature actually help my brain?

Controlled experiments suggest that brief exposure to natural environments can restore directed attention compared to urban settings. A five-minute walk with greenery or even viewing nature images is a high-leverage break during long work bouts.

10) How do I stop thinking about unfinished work at night?

Run a shutdown ritual: capture loose ends, schedule next steps, and say a cue phrase to signal “day over.” Research indicates that making specific plans for unfulfilled goals frees cognitive resources and reduces intrusive thoughts—so you can actually rest.

Conclusion

In a world that constantly competes for your attention, you’ll win by designing your attention. The Pomodoro Technique gives you a reliable on-ramp; timeboxing and time blocking ensure your most valuable work actually happens; batching and single-tasking remove the sand from your gears; and rhythms like 52/17 or 90-minute sprints balance intensity with recovery. Add if–then plans for frictionless starts, shield yourself from noise by moving the phone out of sight and using blockers, and defend daily focus time on your calendar. Finally, close each day with a short shutdown ritual so tomorrow’s attention starts clear. Pick one method above, run it for seven days, then keep or tweak. Focus is a skill—practice it deliberately, track what works, and let your calendar reflect your priorities.

CTA: Choose your method, block your first two focus sessions for tomorrow, and set the timer.

References

- The Pomodoro Technique® (official) — Francesco Cirillo · n.d. · https://francescocirillo.com/pages/pomodoro-technique Wikipedia

- Marc Zao-Sanders, “How Timeboxing Works and Why It Will Make You More Productive,” Harvard Business Review, Dec 12, 2018 · Harvard Business Review

- Cal Newport, “Deep Habits: The Importance of Planning Every Minute of Your Work Day,” blog, Dec 21, 2013 · Cal Newport

- American Psychological Association, “Multitasking: Switching Costs,” n.d. · https://www.apa.org/research/action/multitask dunn.psych.ubc.ca

- Kostadin Kushlev & Elizabeth W. Dunn, “Checking email less frequently reduces stress,” Computers in Human Behavior, 2015 · https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272892107_Checking_email_less_frequently_reduces_stress (summary access) trunk.io

- Nathaniel Kleitman, “Basic rest–activity cycle” (BRAC) and ultradian rhythms: see Sleep and Wakefulness, 1982; summary discussion via Sleep Foundation · Space Frontiers

- Broughton & Ogilvie (eds.), Sleep, Arousal, and Performance, 1995; review of ultradian patterns (discussion via Sleep Foundation page) · https://www.sleepfoundation.org/how-sleep-works/stages-of-sleep Medical Xpress

- “The 52/17 Rule: Genius or Just a Myth?” DeskTime blog, Apr 11, 2024 · https://desktime.com/blog/golden-52-and-17-rule Hachette Book Group

- Chen Berman, Jonides & Kaplan, “The Cognitive Benefits of Interacting with Nature,” Psychological Science, 2008 · https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/83442/Berman%20Jonides%20Kaplan%20Psych%20Science%202008.pdf Bishop House Consulting

- Stothart, Mitchum & Yehnert, “The Attentional Cost of Receiving a Cell Phone Notification,” 2015 (conference paper) · https://clm.psy.fsu.edu/pubs/CSAPoster.pdf Digital CxO

- Ward, Duke & Gneezy, “Brain Drain: The Mere Presence of One’s Own Smartphone Reduces Available Cognitive Capacity,” Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 2017 · https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5506074/ Worklytics

- Locke & Latham, “Building a Practically Useful Theory of Goal Setting and Task Motivation: A 35-Year Odyssey,” American Psychologist, 2002 · https://test1.ctohe.org/sec/docs/GoalSettingFindings.pdf Chicago Journals

- Gollwitzer & Sheeran, “Implementation Intentions and Goal Achievement: A Meta-Analysis,” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 2006 (PDF compilation) · allard.ubc.ca

- Cal Newport, “Drastically Reduce Stress with a Work Shutdown Ritual,” blog, Jun 8, 2009 · Cal Newport

- Masicampo & Baumeister, “Consider It Done! Plan Making Can Eliminate the Cognitive Effects of Unfulfilled Goals,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2011 · (open PDF: ) PubMedusers.wfu.edu

- Mark, Gudith & Klocke, “The Cost of Interrupted Work: More Speed and Stress,” CHI 2008 · UCI Bren School of ICS

- Microsoft Research, “Focus Time: Effectiveness of Computer-Assisted Protected Focus Time at Work,” 2023 · Microsoft

- Hinds & Sutton, “Meeting Overload Is a Fixable Problem,” Harvard Business Review, Oct 28, 2022 · Harvard Business Review