If you’ve ever nailed a workout and then tossed and turned at night, you’ve felt the connection between training time and sleep. This guide explains, in plain language, how exercise timing influences sleep quality—and what to do about it. You’ll learn the nine rules smart sleepers follow to schedule morning, afternoon, and evening sessions so they drift off faster, get more deep sleep, and wake up sharper. This article is educational, not medical advice; if you have a sleep disorder or health condition, speak with a clinician.

Quick answer: Exercise influences sleep through circadian phase-shifting (it can move your body clock earlier or later), thermoregulation (it raises core temperature before sleep), and arousal of the autonomic nervous system. Morning and early-day training often advances your clock and supports earlier sleep, while vigorous workouts ending within ~3–4 hours of bedtime can delay sleep and reduce quality; moderate evening activity finished earlier is usually fine.

1. End Vigorous Workouts at Least 3–4 Hours Before Bed

Vigorous exercise ramps up heart rate, core body temperature, and sympathetic (fight-or-flight) activity—all of which make it harder to fall and stay asleep if they’re still elevated at lights out. The simplest safeguard is a timing buffer: finish high-intensity intervals (HIIT), hard tempo runs, sprints, or max-effort lifts ≥3–4 hours before your target bedtime. Large wearable datasets and lab meta-analyses converge on this guardrail: when late sessions end ≤1 hour before bed, sleep latency rises and total sleep time and efficiency can drop; if workouts end ≥4 hours prior, sleep metrics look similar to rest days.

Numbers & guardrails

- HIIT / vigorous cardio or heavy lifting: aim to finish ≥3–4 hours pre-bed.

- Moderate sessions (steady aerobic, easy lifts): try ≥2–3 hours pre-bed; many people sleep fine.

- Very light activity (stretching, yoga, breathing): typically safe in the last hour.

Why it matters

- Thermoregulation: Sleep onset needs core temperature to fall; late vigorous training delays this drop.

- Autonomic state: High arousal raises nocturnal heart rate and lowers HRV, early markers of poorer sleep. When sessions end earlier, nocturnal HR and HRV normalize.

Mini-checklist

- Plan your last interval to end by ~7:30 p.m. if you target 11:30 p.m. lights out.

- Add a longer cool-down, hydration, and 10–15 minutes of easy walking to accelerate recovery.

- Keep the last hour pre-bed screen-light and caffeine-free (see Rule 8).

Bottom line: The closer a hard workout is to bedtime, the higher the sleep risk; shift intensity earlier and you’ll protect both sleep and recovery.

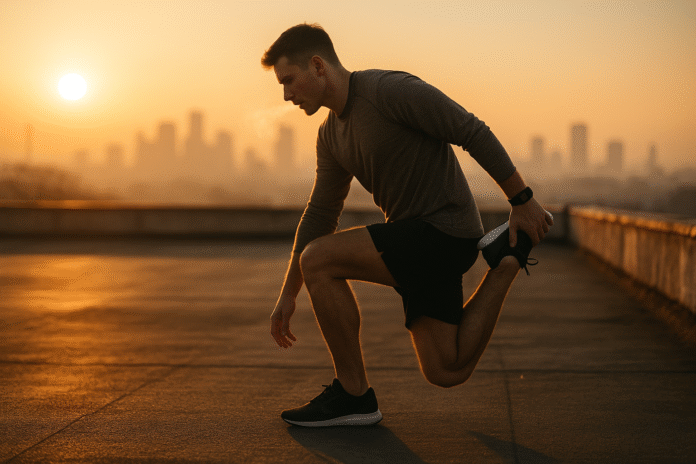

2. Use Morning Exercise to Shift Your Body Clock Earlier

Morning workouts (especially with outdoor light) advance your circadian phase—moving melatonin and sleep earlier—making it easier to fall asleep at a reasonable hour. Laboratory phase-response curves (PRCs) show exercise in the biological morning produces phase advances, while late-evening exercise tends to delay the clock. In practice, training between ~7–10 a.m. with daylight exposure helps those with delayed sleep timing or “night-owl” tendencies start drifting off earlier. Recent RCTs echo this: 12 weeks of morning aerobic training advanced melatonin rhythm and aligned sleep earlier compared with evening training.

2.1 Why it matters

- Consistent mornings = consistent nights. Regular early training builds a stable sleep-wake schedule.

- Light + movement synergy: Daylight is the strongest zeitgeber; pairing it with exercise multiplies phase-advance signals.

2.2 How to do it

- Aim for 20–60 minutes of moderate cardio or a full-body lift within 1–3 hours of wake-up.

- Step outside for at least 20 minutes to stack light with movement.

- Keep breakfast consistent to avoid confusing time cues.

Example: After drifting to sleep at 1:00 a.m., you schedule 8:00 a.m. runs plus daylight. Within 2–3 weeks, your melatonin onset shifts earlier and you comfortably fall asleep before midnight.

Bottom line: Morning training—especially outdoors—nudges your body clock earlier and supports earlier, easier sleep.

3. Target the Afternoon for Performance and Deep Sleep Gains

For many people, late-afternoon exercise (roughly 3–6 p.m.) hits a sweet spot: your core temperature and neuromuscular performance peak, enabling quality work without crowding bedtime. Several studies link afternoon or early-evening exercise with more slow-wave sleep (SWS) that night—a key stage for physical recovery and memory consolidation—likely via thermoregulatory and adenosine mechanisms. One lab study reported a ~33% increase in SWS after diurnal repeated exercise; practically, that can mean waking up with less soreness and better next-day training readiness.

Numbers & guardrails

- Start moderate or heavy sessions by ~5–6 p.m. if you aim for 10–11 p.m. bedtime.

- Build in 10–15 minutes of easy cool-down; finish the last high-intensity bout ≥3 hours pre-bed.

Tools/Examples

- Use a fan or cool shower post-workout to speed temperature drop.

- Track sleep stages and HR/HRV in your wearable to see if afternoon blocks improve SWS.

- If evenings are the only option, progress intensity carefully (see Rule 4).

Bottom line: If your schedule allows, afternoon training balances high performance with sleep-friendly timing and can boost deep sleep the same night.

4. If You Train in the Evening, Modulate Intensity and Extend the Cool-Down

Evening workouts aren’t automatically bad for sleep. Meta-analyses show most evening exercise does not impair sleep as long as it’s not very vigorous right before bed. Problems arise with high cardiovascular strain finishing within ~1 hour of bedtime, which has been linked to later sleep onset, shorter duration, lower quality, higher nocturnal HR, and lower HRV. The workaround: dial the intensity to moderate, finish earlier, and add a longer cool-down and relaxation.

Mini-checklist

- Keep intensity around RPE 5–6/10 (you can talk but prefer not to).

- Finish ≥2–3 hours pre-bed; push intervals to earlier in the session.

- Add 10 minutes of walking + 5–10 minutes of breathwork (e.g., 4-second inhale, 6-second exhale).

- Avoid bright screens and keep the bedroom <20°C / 68°F for faster sleep onset.

Why it matters

- Autonomic downshift: A longer cool-down and slow breathing help parasympathetic rebound.

- Temperature drop: Gentle movement and a cool room restore the gradient needed to fall asleep.

Bottom line: You can keep training after work—just finish earlier, lower the peak strain, and cool down longer to protect sleep.

5. Match Modality to Timing: Strength Often Later, HIIT Earlier

Not all exercise affects sleep the same way when performed late. Evidence suggests strength/resistance training is generally sleep-friendly, sometimes even in the evening, while high-strain cardio close to bedtime is riskier. Reviews comparing modalities indicate strengthening exercise shows strong efficacy for improving sleep, and several trials and cohort analyses suggest resistance training in the late day can work, provided the final heavy set still ends hours before bed. When in doubt, do HIIT earlier and save technique or accessory lifts for later slots. ScienceDirect

How to apply it

- Morning: HIIT, tempo runs, track work, metabolic circuits.

- Afternoon: Main lifts, sport practice, steady cardio.

- Evening (earlier): Accessory lifts, mobility, easy aerobic, yoga, or a walk.

Numbers & guardrails

- Keep last heavy compound lift ≥3 hours pre-bed; accessory work can finish ~2 hours pre-bed.

- If you must do HIIT at night, shorten intervals, lengthen rest, and finish ≥4 hours pre-bed.

Bottom line: Place high-strain cardio earlier in the day and reserve lower-arousal modalities for later, especially if evenings are your only window.

6. Align Training With Your Chronotype—Or Use It to Shift One

Your chronotype (morning lark vs night owl) changes how you respond to training time. Controlled studies show earlier chronotypes advance further with morning exercise and may delay with evening sessions, while later chronotypes often tolerate later training better. That said, if you want to shift from night owl to a healthier schedule, morning exercise plus daylight is one of the most reliable levers to advance your clock within a few weeks. Adjust expectations: the “best” time is the one you can do consistently—and the one that supports your target bedtime. PMC

H3: Practical mapping

- Morning types: Keep key sessions in the morning; avoid very late competitions and high-strain nights.

- Evening types: You may perform better later, but if sleep is late or short, use morning exercise to pull the night earlier.

- Everyone: Anchor sessions to a consistent daily window to reinforce rhythm.

Mini-case

- A self-described night owl moves lifts from 8:30 p.m. to 5:45 p.m. and adds a 20-minute 8:00 a.m. walk. Within 2–3 weeks, lights out shifts from 1:00 a.m. to ~11:30 p.m., with shorter sleep latency and more energy at work.

Bottom line: Train when you can be consistent, but lean on morning exercise and daylight to move a delayed clock earlier.

7. For Shift Work and Jet Lag, Treat Exercise as a Time Cue

Exercise is a bona fide zeitgeber (time cue): when timed strategically, it helps realign your circadian rhythm after travel or during rotating shifts. PRC data in humans show morning-local exercise advances the clock; late-evening/night exercise delays it. For eastbound travel (where you need to sleep earlier), use local-morning exercise + light; for westbound (later sleep), cautiously place late-afternoon exercise and avoid high-intensity sessions close to your new bedtime. For shift workers, establish a repeatable pre-sleep wind-down and keep high-strain training during your biological “day”, not just the clock day.

Region-specific notes (as of Aug 2025)

- Eastward 8–10 time zones: Short ~20–40 min easy runs or cycles in bright morning light for 3–4 days; avoid vigorous night sessions.

- Westward travel: Place moderate training mid- to late-afternoon local time; avoid late-night light-soaked gyms if sleep onset is a struggle.

Checklist

- Pair exercise with timed light; avoid caffeine after local midday in the new zone.

- Keep sleep opportunity ≥7 hours during transitions (AASM recommendation).

Bottom line: Timed correctly, exercise helps reset your clock—crucial for travelers and shift workers trying to protect sleep.

8. Space Caffeine, Meals, and Naps Around Late Workouts

Even perfectly timed training can be undone by late caffeine, heavy meals, or long naps. Randomized trials and systematic reviews show caffeine taken even 6 hours before bed can reduce sleep by ~40–60 minutes and lengthen sleep-onset latency. If you train late, start a caffeine cut-off 8–12 hours before bedtime (earlier for sensitive people), and keep post-workout meals lighter, finishing 2–3 hours pre-bed. Keep naps to 10–20 minutes before 3 p.m. so they don’t push bedtime later.

Mini-checklist

- Caffeine: Last dose before ~2 p.m. if lights out is 10–11 p.m.; earlier if you notice insomnia.

- Meals: Favor protein + complex carbs, stop 2–3 hours pre-bed; skip very spicy/fatty foods late.

- Naps: 10–20 minutes early afternoon; avoid >30–60 minutes late naps that fragment sleep.

Bottom line: Training late? Pull stimulants earlier, keep meals lighter, and nap smart to protect the night.

9. Build Volume Consistently; Let Sleep Guide Intensity

Across populations, regular physical activity improves sleep quality—shortening sleep-onset latency, increasing deep sleep, and reducing insomnia symptoms. Global guidelines recommend 150–300 minutes/week of moderate or 75–150 minutes/week vigorous activity, plus strength work on 2+ days—targets that also align with better sleep in reviews. The practical rule: make movement predictable and let last night’s sleep guide today’s intensity. If your wearable shows elevated resting HR, low HRV, or you feel poorly rested, swap to an easier session or rest day. Your sleep will often rebound within 24–48 hours, and your next hard workout will be better. PubMed

Why it matters

- Sleep ↔ training loop: Poor sleep degrades performance and raises injury risk; better sleep enhances adaptation and recovery.

- Consistency beats perfection: The nervous system loves repeatable rhythms; scattered “hero sessions” at odd hours can backfire.

Mini-plan

- Hit 3–5 days/week of movement; schedule two key sessions when you sleep best (often morning or afternoon).

- Track sleep and training for 2–4 weeks; if late sessions consistently hurt sleep, move them earlier.

- Protect 7+ hours in bed—that recovery time is where adaptations consolidate.

Bottom line: Keep moving most days, respect recovery signals, and let sleep quality steer intensity so you improve without burning out.

FAQs

1) Is working out before bed always bad for sleep?

No. Meta-analyses show most evening exercise doesn’t harm sleep unless it’s vigorous and ends within about an hour of bedtime. If evening is your only slot, keep intensity moderate, end earlier, and add a longer cool-down. Many people sleep normally with that approach.

2) What’s the single best time of day to exercise for sleep?

There isn’t one universal best time, but morning and afternoon offer reliable advantages: morning sessions (with daylight) advance your clock so you fall asleep earlier; afternoon training taps a performance peak and still leaves plenty of buffer before bed. Choose the window you can repeat consistently.

3) How close to bedtime is “too close” for HIIT?

As a rule, finish HIIT ≥3–4 hours before lights out. Large datasets suggest that when strenuous sessions end ≥4 hours pre-sleep, effects on sleep are negligible; when they end closer, sleep often suffers (later onset, shorter duration, higher nocturnal HR).

4) Do strength workouts interfere with sleep less than cardio?

Often, yes—resistance training tends to be sleep-friendly compared with high-strain cardio late at night, especially if you finish a few hours before bed. Reviews indicate strengthening exercise is effective for improving sleep, whereas very hard evening cardio is more likely to disrupt it. fmch.bmj.com

5) Can I use exercise to fix jet lag?

Yes. Pair local-morning exercise and bright light to shift your body clock earlier after eastbound travel; time late-afternoon exercise and avoid late-night light after westbound trips. Keep high-intensity work away from your new bedtime during the first days. Frontiers

6) How does caffeine timing interact with late workouts and sleep?

Caffeine is a potent sleep disrupter when taken late; trials show doses as early as 6 hours before bedtime can cut sleep by ~40–60 minutes. If you train in the late afternoon or evening, move caffeine earlier (aim for a cut-off 8–12 hours pre-bed for sensitive sleepers). PMCAASM

7) Do wearables help me optimize workout timing for sleep?

They can. Track sleep onset, duration, SWS/REM (with caution), resting HR, and HRV after sessions at different times. Look for patterns over 2–4 weeks, not single nights. If later sessions raise nocturnal HR and lower HRV, shift intensity earlier or swap to lighter evening modalities.

8) I’m a night owl. Should I force morning workouts?

If your bedtime is too late for your lifestyle, morning exercise + daylight is a proven way to advance your clock. Start gently (even 20–30 minutes) and add consistency before intensity. If your schedule allows late training and you sleep well, you don’t have to change. PMC

9) What weekly training volume is best for sleep?

Global public-health guidelines recommend 150–300 min/week moderate or 75–150 min/week vigorous activity, plus 2+ strength days—levels associated with better sleep in observational and interventional research. Spread volume across the week and avoid cramming. PMC

10) Does evening yoga or a walk help sleep?

Yes—low-intensity evening movement (yoga, stretching, a relaxed walk) can reduce stress and support sleep, particularly if it ends ~1–2 hours before bed and is followed by a wind-down routine. Keep intensity low and screens off afterward. Sleep Foundation

11) Can exercise change my REM or deep sleep?

Short-term, acute exercise often increases SWS and may reduce REM depending on intensity and timing; chronic training typically improves sleep efficiency overall. Track your personal response across weeks to spot trends.

12) I slept terribly last night—should I still train today?

Yes, but reduce intensity or duration and prioritize technique/aerobic base. Sleep loss impairs performance and raises injury risk; swapping to an easy session or rest can protect the rest of your week and help sleep rebound. PMC

Conclusion

The way exercise timing influences sleep quality comes down to three levers: circadian phase, temperature regulation, and autonomic arousal. Morning and early-day exercise—especially with daylight—advances your clock and supports earlier, easier sleep. Afternoon training lands at a performance sweet spot and can increase deep, restorative sleep the same night. Evening exercise is workable too—if you avoid peak strain close to bedtime, extend your cool-down, and manage caffeine, meals, and light. Your chronotype and schedule matter, so build a routine you can repeat.

Put this into practice: pick two high-quality sessions at times that support your bedtime (morning or afternoon for most), keep evening work moderate, and finish hard efforts ≥3–4 hours pre-bed. Track your sleep and recovery markers for a few weeks. Adjust based on what your nights tell you. Done consistently, you’ll train better, fall asleep faster, and wake up with more in the tank.

CTA: This week, move one key workout earlier by 2–3 hours and pair a short morning session with daylight—then note what changes in your sleep.

References

- Effects of Evening Exercise on Sleep in Healthy Participants, Sports Medicine, Stutz et al., 2019. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40279-018-1015-0

- Human Circadian Phase–Response Curves for Exercise, The Journal of Physiology, Youngstedt et al., 2019. https://physoc.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1113/JP276943

- Dose–response relationship between evening exercise and subsequent sleep, Nature Communications, Leota et al., 2025. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-58271-x

- How Can Exercise Affect Sleep?, Sleep Foundation (review updated July 2025). https://www.sleepfoundation.org/physical-activity/exercise-and-sleep

- The effects of physical activity on sleep: a meta-analytic review, Journal of Behavioral Medicine, Kredlow et al., 2015. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10865-015-9617-6

- World Health Organization 2020 Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour, WHO/BJSM summary, 2020. https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/54/24/1451

- Adult Activity Guidelines, CDC, updated Dec 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/physical-activity-basics/guidelines/adults.html

- Differential benefits of 12-week morning vs evening aerobic exercise on sleep and cardiometabolic health, Scientific Reports, Shen et al., 2025. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-02659-8

- Diurnal repeated exercise promotes slow-wave activity and SWS, Sleep Medicine, Aritake-Okada et al., 2019. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31095458/

- Caffeine Effects on Sleep Taken 0, 3, or 6 Hours before Bedtime, Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, Drake et al., 2013. https://jcsm.aasm.org/doi/10.5664/jcsm.3170

- The effect of caffeine on subsequent sleep: systematic review and meta-analysis, Sleep Medicine Reviews, Gardiner et al., 2023–2025 updates. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1087079223000205 and https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article/48/4/zsae230/7815486

- The impact of exercise on sleep and sleep disorders, npj Biological Timing and Sleep, Korkutata et al., 2025. https://www.nature.com/articles/s44323-024-00018-w

- Sleep and the athlete: narrative review and 2021 expert consensus, British Journal of Sports Medicine, Walsh et al., 2021. https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/55/7/356

- Seven or more hours of sleep per night: A health necessity for adults, American Academy of Sleep Medicine, updated July 2024. https://aasm.org/seven-or-more-hours-of-sleep-per-night-a-health-necessity-for-adults/