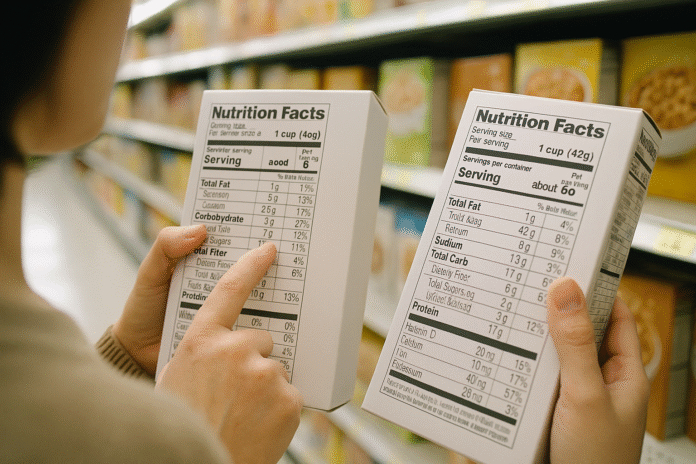

Food labels can be confusing, especially when one line says “serving size,” another says “servings per container,” and the calories jump when you flip from “per serving” to “per container.” This guide makes it simple. You’ll learn how serving size is set, what your portion actually is, and how to calculate whole-package nutrition without a calculator. You’ll also master % Daily Value (%DV), dual-column labels, and the differences between “per serving” (common in the U.S./Canada) and “per 100 g” (standard in the EU/UK).

In short: the serving size is the legally defined amount on the Nutrition Facts label; your portion is what you choose to eat; “per container” tells you the totals if you finish the entire package.

1. Know Exactly What “Serving Size” Means (and What It Doesn’t)

A serving size on the Nutrition Facts panel is a legal baseline, not a recommendation. In the U.S., it’s tied to “reference amounts customarily consumed” (RACCs)—national food-consumption data that estimate how much people typically eat in one sitting. That means the serving size is descriptive, not prescriptive: it reflects what many people do, not what you personally should do today. As of August 2025, manufacturers must translate those RACCs into household measures you recognize (e.g., 2/3 cup, 1 slice, 1 bottle), so you can compare products quickly and consistently. You’ll also see “servings per container,” which can be 1 for single-serve or more for multi-serve packages. Understanding this point prevents two common errors: assuming the label’s serving is “healthy for you,” and assuming the entire package equals one serving. Legal Information Institute

1.1 Why it matters

- It stops you from mistaking a labeling unit for personal advice.

- It helps apples-to-apples comparisons between brands in the same category.

- It sets the stage for accurate calorie and %DV math later on.

1.2 Numbers & guardrails (U.S.)

- RACCs come from national surveys; companies must convert RACCs into familiar household measures on the label.

1.3 Mini-checklist

- Read “Serving size” first.

- Note the unit (cups, grams, pieces).

- Check “Servings per container” before planning your portion.

Synthesis: Treat serving size as the ruler on the label—not a diet rule for your life. Once you have the ruler, everything else measures up.

2. Separate “Portion” (What You Eat) from “Serving Size” (What’s on the Label)

A portion is the amount you actually put on your plate, which may be smaller or larger than the serving size. That distinction is where most calorie surprises happen. Your portion depends on context—your hunger, activity, age, medical needs, and whether it’s a snack or a meal. A label might say 2/3 cup cereal per serving, but your everyday bowl might hold 1½–2 cups. Conversely, a 1-bottle serving for a drink might be more than you want at once. If you’re feeding kids or athletes, portions will differ from the “average adult” baseline implied by the label. Making portion decisions deliberately—rather than defaulting to package size or plate size—keeps your nutrition aligned with your goals.

2.1 How to right-size your portion

- Check the serving first, then decide: do you want ½ serving, 1 serving, 1½, or 2?

- Use household tools: a measuring cup for cereal, a standard spoon for peanut butter, or a kitchen scale when precision matters.

- Pre-portion snacks into small containers or bags to avoid “bottom-of-the-bag” eating.

2.2 Common mistakes

- Equating “single-serve looking” packaging with one serving.

- Thinking the label’s serving is automatically the “healthy” amount.

- Forgetting to double or triple calories when your portion is 2–3 servings.

2.3 Region note (UK/EU)

Portion advice often appears alongside required per 100 g/ml data; the per-portion number is optional and defined by the manufacturer, so always compare within the same basis (per 100 g vs per 100 g) before switching to a portion view.

Synthesis: Your portion is your choice. Use the serving size as a reference point, then match your portion to your plan.

3. Single-Serve vs. Multi-Serve—and When Dual-Column Labels Apply

Not every “small” package is legally single-serve. In the U.S., a product is a single-serving container if it holds less than 200% of the applicable RACC—so the full container is labeled as one serving (think a 20-oz soda). When a package contains at least 200% and up to 300% of its RACC, it generally must use dual-column labeling: one column for the RACC-based serving and one for the entire container. This makes it crystal-clear what you get if you finish the whole thing. There are exceptions for very small labels (tabular/linear formats) and some other special cases, but dual-column displays are now common on drinks, chips, and frozen meals you could plausibly consume in one go. As of August 2025, you might also see voluntary dual columns on some items just under the 200% threshold to aid comparison.

3.1 How to use dual-column labels

- Read both columns: “Per serving” for comparisons; “Per container” for reality checks.

- If you plan to eat the lot, use the per container numbers for your diary.

- If you’ll split it, decide upfront: ½ container now, ½ later—then log accordingly.

3.2 Numeric example

A chips bag lists 140 kcal per serving (1 oz, 28 g), 2.5 servings per bag, and 350 kcal per container in the second column. If you eat the whole bag on your commute, you ate 350 kcal, not 140.

3.3 Region note (Canada)

Single-serving products must declare the entire net quantity as the serving size; multi-serve packages show “per serving” with “servings per container.” Dual-style displays may appear when helpful, especially on products easily eaten in one sitting. Canadian Food Inspection Agency

Synthesis: Dual columns translate label theory into real-life totals. Use them to avoid accidental “stealth calories.”

4. Master the Math: From “Per Serving” to “Per Package” in Seconds

Label math is straightforward once you set your portion. Multiply per-serving numbers by the number of servings you actually eat. If a frozen entrée is 310 kcal per serving with 2 servings per tray, eating the whole tray is 310 × 2 = 620 kcal. For %DV, the math is identical: 8% DV iron per serving × 2 servings = ~16% DV for your portion. When packages use dual-column labels, you can skip the math and read the per-container column directly. For items given in grams or milliliters, match your portion with a simple ratio. Example: a sauce is 60 kcal per 30 ml (2 Tbsp). If you pour 45 ml, that’s 1.5 servings → 90 kcal. Keep an eye on energy-dense add-ons—oils, dressings, nut butters—where small overpours add up fast.

4.1 Quick math checklist

- Confirm servings per container.

- Decide your portion: ½, 1, 1½, 2 servings.

- Multiply calories/macros and %DV by that factor—or read the per container column.

- For metric volumes/weights, scale linearly (e.g., 45 ml is 1.5× a 30 ml serving).

4.2 Small tools that help

- A 1-cup measuring cup near the cereal shelf.

- A teaspoon/Tbsp for oils and dressings.

- A kitchen scale for baking, nuts, cheese, and meats.

Synthesis: Two questions—How much is a serving? How much am I eating?—turn label math from guesswork into clarity.

5. Decode % Daily Value: What 5% and 20% Actually Signal

%DV tells you how much one serving contributes to a standard daily target. On U.S. labels, 5% DV or less is low, 20% DV or more is high. That shorthand helps you prioritize nutrients: aim higher for fiber, calcium, potassium, iron; aim lower for sodium, saturated fat, and added sugars. Remember, %DV is based on a 2,000-calorie reference pattern; it’s a comparison tool, not a personalized prescription. As of March 2024, the Daily Value for added sugars is 50 g, so a serving with 25 g added sugars shows 50% DV. Knowing these thresholds ensures quick, consistent decisions across snacks, cereals, sauces, and drinks—even when serving sizes differ.

5.1 How to use %DV in the aisle

- Choose more: fiber, calcium, potassium, iron (look for ≥20% DV when feasible).

- Limit: sodium, saturated fat, added sugars (aim for ≤5–10% DV per serving, context-dependent).

- Compare similar products using %DV when serving sizes are close.

5.2 Mini case

Two granolas:

- Brand A: 10% DV fiber, 6% DV saturated fat, 22% DV added sugars per serving.

- Brand B: 18% DV fiber, 4% DV saturated fat, 8% DV added sugars per serving.

If taste and price are equal, Brand B aligns better with most nutrition goals.

Synthesis: %DV is your traffic light: red-flag highs for “limit” nutrients and green-light highs for “get enough” nutrients.

6. “Per 100 g/ml” vs. “Per Serving”: Comparing Across Regions

In the EU and UK, nutrition declarations must appear per 100 g or 100 ml (with optional per-portion data), which makes cross-brand comparisons simple even when serving sizes differ. In the U.S./Canada, labels emphasize per serving and per container, which makes portion planning straightforward. The key is to compare on the same basis. If you’re shopping in London and comparing yogurt, use the per 100 g column to decide between brands; if you’re meal-planning in Toronto, use per serving and adjust to your portion. Many packages show both. When front-of-pack systems (like UK traffic lights) appear, they usually rely on per 100 g thresholds, sometimes supplemented by per portion values for large portions. Food Safety Authority of Ireland

6.1 How to compare fairly

- EU/UK: Compare brands using per 100 g/ml numbers, then check the portion you’ll actually eat.

- U.S./Canada: Compare similar serving sizes or use %DV to normalize differences.

- Watch for drained weight (e.g., canned tuna, beans) when relevant.

6.2 Practical tip

If a granola is 480 kcal per 100 g and you typically eat 60 g, your portion is 288 kcal. If the label also lists 45 g per serving, that serving is 216 kcal—use whichever basis matches your bowl.

Synthesis: Match basis to basis for comparisons; then translate to the portion you plan to eat.

7. Liquids, Discrete Units, and Variable-Size Foods: Reading Beyond the Basics

Not all foods fit neatly into cups or spoons. Drinks and soups list milliliters/fluid ounces; items like muffins or cookies are discrete units; produce, fish, and pickles vary in size and may use weights with a visual cue (e.g., “about 1 spear”). For discrete units, serving-size rules consider how a unit compares to the category’s RACC. If a muffin weighs ≥67% and <200% of the RACC, a single unit is the serving; if it’s ≥200% and ≤300%, expect dual-column labeling (per serving and per unit). For variable items (e.g., whole fish), labels often use ounces/grams with an appropriate visual cue to help you picture the amount. This is where a kitchen scale and a quick label read prevents under- or over-counting.

7.1 Tools/Examples

- Discrete unit: 1 large muffin = 1 serving if it’s between 67% and <200% RACC; dual columns if 200–300% RACC.

- Variable size: “1 pickle (30 g)”—weighing helps when pickles vary widely.

- Liquids: Measure “per 240 ml (1 cup)” vs what your mug actually holds.

7.2 Mini-checklist

- Identify if the food is a liquid, discrete unit, or variable size.

- Apply the relevant rule and confirm whether a dual column should be present.

- Use simple tools (scale/measure) to match your portion.

Synthesis: Identify the type of food on the label first; the correct rule—and accurate tracking—follows naturally.

8. Multipacks, “Per Unit” Info, and Tricky Packaging

Multipacks (e.g., a box of 6 granola bars) often list nutrition per bar and may also show per serving if a serving equals more than one unit. Some single-serving containers hold multiple individually wrapped units (e.g., two mini sandwiches in one wrap). As of August 2025, U.S. rules allow an additional voluntary column per unit even on single-serve containers with more than one discrete unit; this helps you see unit-by-unit numbers without changing the official serving size. Also note the “looks-single-serve” trap: some small-ish packages actually contain 2–3 servings; if they’re between 200–300% of the RACC, dual-column labeling should make that clear. When space is limited (tiny packages), exemptions can apply and formats may change (tabular/linear), but the principle stays the same—look for per unit, per serving, and per container to keep your math honest.

8.1 Common packaging pitfalls

- Share-size snacks: 2–3 servings masquerading as “one snack.”

- Mini bottles/cans: May be 1–2 servings depending on volume and category RACC.

- Combo packs: Check if the listed serving includes all components (e.g., crackers + cheese).

8.2 How to handle multipacks

- Treat each unit (bar, cup, bottle) as one portion unless the label defines otherwise.

- For value packs, multiply per unit by units consumed.

- When in doubt, scan for dual columns or per unit details before eating.

Synthesis: Packaging can play visual tricks; numbers won’t. Hunt for per unit, per serving, and per container to keep perspective.

9. A Fast, Repeatable Workflow for the Aisle and the Kitchen

You don’t need to be a dietitian—or a mathematician—to use labels well. A consistent 60-second routine keeps choices aligned with your goals:

First, decide your context. Is this a meal or a snack? Are you looking for more fiber/protein or keeping an eye on sodium/added sugar? Then follow the same simple path every time.

9.1 60-second label workflow

- Find the ruler: Read Serving size and Servings per container.

- Pick your portion: ½, 1, 1½, or 2 servings (or check per container).

- Scan %DV: Aim high for “get more” nutrients; aim low for “limit” ones (5% low, 20% high).

- Check the catch: Dual-column panels, small-print units (g/ml), and energy-dense add-ons.

- Confirm region basis: Per 100 g/ml (EU/UK) vs per serving/container (U.S./Canada) before comparing across brands.

9.2 Mini case: choosing a yogurt

- Brand A (per 100 g): 62 kcal, 0.2 g sat fat, 8.5 g sugar, 6 g protein.

- Brand B (per 100 g): 92 kcal, 1.8 g sat fat, 12 g sugar, 8 g protein.

You eat 150 g portions. Multiply each line by 1.5 and pick based on your priorities (e.g., lower sugar vs higher protein).

Synthesis: One routine, everywhere you shop or cook. Once you lock it in, labels turn from clutter into clarity.

FAQs

1) Is a serving size a recommendation for how much I personally should eat?

No. A serving size is a standardized labeling unit based on typical consumption, not a prescription for you. Use it to compare products and to scale nutrition to your portion. For example, if a serving is 2/3 cup but you prefer 1 cup, multiply everything by ~1.5. The label’s job is consistency; your job is fit and context.

2) What does “servings per container: about 2” mean?

It means the package holds roughly two label servings—maybe 1.8 or 2.2 depending on fill. If you eat the whole package, use the per container numbers (or multiply per serving by 2). Dual-column labels, when present, save you the math.

3) How do %DV numbers help if my calorie needs aren’t 2,000 per day?

%DV is a comparison tool. Even if you need 1,600 or 2,600 kcal, the 5% low / 20% high guidance still flags nutrients to limit or prioritize. You can still compare two soups’ sodium quickly: 8% DV vs 24% DV is meaningfully different regardless of your exact energy target.

4) Are dual-column labels only for big packages?

They’re for packages that fall into a specific window—generally ≥200% and ≤300% of the RACC—or for some products that voluntarily add columns to improve clarity. If you could reasonably eat the container in one sitting, dual columns help you see both the per-serving and per-container totals.

5) Why do European labels use “per 100 g/ml” instead of per serving?

EU law standardizes declarations per 100 g/ml to make brand comparisons straightforward. Per-portion info can appear too, but the per-100 basis is mandatory. In the UK, front-of-pack systems often key off per-100 thresholds.

6) What’s the DV for added sugars, and why is it on labels now?

As of March 2024, the DV for added sugars is 50 g (for a 2,000-kcal pattern). Added sugars are distinct from naturally occurring sugars (e.g., in milk or fruit). Seeing added sugars helps you gauge sweets, cereals, yogurts, and sauces quickly.

7) How do I handle restaurant items with no labels?

Use experience from packaged foods: estimate portion size (cups, Tbsp, grams) and map to a similar labeled item (e.g., chain restaurant data or a grocery equivalent). Prioritize high-impact items (oils, dressings, sugary drinks). When in doubt, assume generous portions and add a margin.

8) What about kids—should I use the same label logic?

The logic is the same, but portions are smaller and nutrient focuses can differ. For packaged foods, read serving size as the baseline ruler, then scale to the child’s appetite and needs. Look for lower added sugars and sodium, and keep an eye on choking-hazard sizes for small children.

9) How do I compare cereal when one brand lists 55 g per serving and another lists 40 g?

Convert to a common basis. %DV helps, but you can also compare per 100 g if it’s provided or do the math: scale each brand to the amount you actually pour (e.g., 60 g). Once you normalize, differences in sugar/fiber/protein become clearer.

10) Do measuring cups and scales really matter?

They matter when precision matters—baking, calorie-dense foods (nuts, cheese, oils), or specific health goals. Most days, quick visual cues are fine. Use tools where small overpours would disproportionately change your totals.

11) Why do some tiny packages feel like they should be one serving but aren’t?

Some packages visually look single-serve but are legally multi-serve based on RACCs. In the U.S., products between 200–300% of RACC often require dual-column labels to show per-serving and per-container numbers. If the label is tiny, a tabular/linear format might be used.

12) What’s the fastest way to avoid “portion creep”?

Decide your portion before you start eating; pre-portion snacks; pour dressings/oils with a spoon; and glance at %DV to keep “limit” nutrients in check. Building that 60-second routine from Rule 9 prevents accidental upsizing.

Conclusion

Once you separate the serving size (label ruler) from your portion (real life), the whole label snaps into focus. Dual-column displays show you the whole-package reality; %DV thresholds quickly flag nutrients to seek or limit; and a consistent workflow turns comparison shopping into a habit, not a chore. The key is matching basis to basis (per serving, per container, or per 100 g/ml), then translating those numbers into the portion you actually plan to eat. Over time, your eye will catch the big rocks first—servings per container, added sugars, sodium, fiber—so you can align choices to your goals in under a minute.

Take this article to your next grocery run and test the 60-second routine. After two or three aisles, you’ll feel the difference. Pick one product today and practice the per-serving vs per-container check—then build from there.

References

- How to Understand and Use the Nutrition Facts Label. U.S. Food & Drug Administration (Mar 5, 2024). https://www.fda.gov/food/nutrition-facts-label/how-understand-and-use-nutrition-facts-label

- Serving Size on the Nutrition Facts Label. U.S. Food & Drug Administration (Mar 5, 2024). https://www.fda.gov/food/nutrition-facts-label/serving-size-nutrition-facts-label

- Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels. U.S. Food & Drug Administration (Mar 5, 2024). https://www.fda.gov/food/nutrition-facts-label/daily-value-nutrition-and-supplement-facts-labels

- Added Sugars on the Nutrition Facts Label. U.S. Food & Drug Administration (Mar 5, 2024). https://www.fda.gov/food/nutrition-facts-label/added-sugars-nutrition-facts-label

- 21 CFR § 101.12 — Reference amounts customarily consumed per eating occasion. eCFR, U.S. Government Publishing Office (current as accessed Aug 2025). https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-B/part-101/subpart-A/section-101.12

- Guidance for Industry: Serving Sizes of Foods That Can Reasonably Be Consumed at One Eating Occasion; Dual-Column Labeling. U.S. Food & Drug Administration (accessed Aug 2025). https://www.fda.gov/media/133699/download

- Nutrition labelling — Food information to consumers legislation. European Commission (May 20, 2020). https://food.ec.europa.eu/food-safety/labelling-and-nutrition/food-information-consumers-legislation/nutrition-labelling_en

- Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 on the provision of food information to consumers. EUR-Lex (Oct 25, 2011). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2011/1169/oj/eng

- Nutrition labelling: Nutrition Facts table. Health Canada (Sep 5, 2024). https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/nutrition-labelling/nutrition-facts-tables.html

- How to read food labels. NHS (accessed Aug 2025). https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/eat-well/food-guidelines-and-food-labels/how-to-read-food-labels/