If you’ve ever wondered exactly how much to drink each day—and why your needs seem to change—this guide is for you. Below, you’ll learn an evidence-based framework to set your baseline, then adjust it for age, climate, activity, illness, and life stage. In short: most healthy adults can start with established “adequate intake” (AI) ranges and then tune up or down using simple, real-world signals like urine color, thirst, and body mass changes. The fast answer: the U.S. National Academies suggest about 3.7 L/day for men and 2.7 L/day for women (total water from all foods and beverages), while Europe’s EFSA suggests 2.5 L and 2.0 L, respectively; about 20% typically comes from foods. Your true target shifts with sweat, heat, altitude, pregnancy/lactation, and illness.

Medical disclaimer: This article is educational and not a substitute for personalized medical advice. If you have kidney, heart, or endocrine conditions—or are on fluid-sensitive medications—talk to your clinician about individualized fluid goals.

Skim-this-first plan:

- Set your baseline from standards.

- Adjust for body size/age.

- Add for heat/humidity.

- Match to exercise & sweat rate.

- Use urine color feedback.

- Adapt for pregnancy/lactation.

- Use ORS when ill.

- Balance electrolytes & avoid overhydration.

- Count all fluids (with caffeine caveats) and limit alcohol/sugar.

- Convert units & plan your day.

- Tailor for kids, older adults, altitude, and travel.

1. Lock in an Evidence-Based Baseline (Then Personalize)

The most reliable way to begin is to anchor your daily water intake to authoritative recommendations and then personalize. For healthy adults in temperate conditions, the U.S. National Academies’ Adequate Intakes (AIs) are ~3.7 L/day for men and ~2.7 L/day for women, counting all beverages and moisture from food. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) sets slightly lower AIs: 2.5 L/day for men and 2.0 L/day for women under moderate activity and temperature. About 20% of total water comes from food on a typical diet; the rest is beverages (plain water, coffee/tea, milk, etc.). Start here, then fine-tune based on your environment, sweat, and health cues.

1.1 Numbers & guardrails

- U.S. NAM (IOM/NASEM): 3.7 L (men), 2.7 L (women), total water from foods + drinks.

- EFSA (EU): 2.5 L (men), 2.0 L (women), assuming ~moderate climate/activity; adolescents ≥14 often use adult values.

- Food contribution: Roughly 20% of total water commonly comes from foods.

1.2 How to apply it today

- Start with the AI for your sex.

- Track how you feel and perform (energy, focus, GI comfort), and check your urine color (aim for pale yellow—see Rule 5).

- If most of your day is sedentary, cool, and indoors, you may live comfortably a bit below your AI; if you’re active or it’s hot, you’ll need more.

- Reassess weekly as seasons, workloads, or routines change.

Bottom line: The baseline keeps you honest; the personalization keeps you accurate.

2. Adjust for Body Size, Age, and Real-World Variability

Even with a solid baseline, body size, age, and day-to-day conditions push needs up or down. Larger bodies often need more fluid; smaller bodies, less. Children’s targets scale with growth; older adults often need deliberate drinking because thirst cues may weaken with age, and kidneys concentrate urine less effectively. Large global datasets also show that water turnover (how quickly your body cycles water) varies significantly by age, sex, climate, and activity—evidence that a single number can’t fit everyone.

2.1 Numbers & guardrails

- Children (NAM via Harvard): Rough daily beverages (8 oz cups): 1–3 y: 4 cups; 4–8 y: 5 cups; 9–13 y: 7–8 cups; 14–18 y: 8–11 cups; adults: 13 cups (men), 9 cups (women), pregnancy 10, breastfeeding 13. These beverage targets sit within total-water AIs (foods add more).

- Older adults: Thirst sensation and urine-concentrating ability can decline with age; dehydration is common in care settings, so proactive, scheduled drinking helps.

2.2 Mini-checklist

- Smaller frame, cooler climate, low activity? Baseline −5–15%.

- Larger frame, hot/humid climate, high activity? Baseline +10–30% (then refine via Rules 3–5).

- Over 65? Set reminders, pair fluids with meals/snacks, and use favorite cups/bottles within reach.

Bottom line: Size and age set the stage; climate and activity write the day’s script.

3. Add for Heat and Humidity (Safely)

Hot, humid weather raises sweat losses; you’ll need to drink more—but not without limits. Field guidance for workers and travelers emphasizes balancing intake to thirst while avoiding overdrinking that leads to dangerously low blood sodium (hyponatremia). A practical safety cap from heat-stress guidance is no more than ~1.5 quarts (~1.4 L) per hour of fluids. In prolonged heat or heavy work, include some salt from food or appropriately formulated drinks.

3.1 How to do it

- Track conditions (heat index/WBGT) and how you feel: headache, nausea, confusion, cramps signal trouble.

- Drink enough to relieve thirst and keep urine light-colored; don’t force gallons.

- For multi-hour heat exposure, add sodium via meals/snacks (e.g., crackers, pretzels) or a sports beverage; most standard sports drinks are not salty enough alone for extreme durations.

3.2 Mini case

You’re landscaping in hot, humid weather for 3 hours. Start well-hydrated, then sip regularly (e.g., ~400–800 mL/h split into small doses), include a salty snack at breaks, and never exceed ~1.4 L/h. Afterward, check urine color and how you feel; if wiped out or cramping, you likely under-replaced sodium and/or fluid.

Bottom line: Drink more in the heat, but cap hourly intake and include salt for long, sweaty bouts.

4. Match Intake to Exercise and Your Sweat Rate

During exercise, aim to limit body mass loss to <2% and avoid weight gain from overdrinking. Typical drinking ranges during endurance work fall around ~0.4–0.8 L per hour, but the best plan is personal: weigh before/after to estimate sweat rate and replace accordingly. For faster post-workout rehydration, a common sports-nutrition recommendation is ~1.5 L per kilogram of body mass lost (includes ongoing urine/sweat losses during recovery).

4.1 How to do it

- Estimate sweat rate: (Pre-exercise weight − Post-exercise weight + fluids consumed − urine) ÷ hours.

- During: Start sipping early; don’t wait for intense thirst.

- After: If you lost 1.0 kg, target ~1.5 L over the next few hours, plus sodium via food.

4.2 Common mistakes

- Chugging large boluses infrequently (leads to sloshing and bathroom runs).

- Gaining weight during long sessions—classic overhydration red flag.

Bottom line: Train with your bottle the way you train your legs—measure, practice, and personalize.

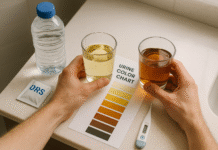

5. Use Urine Color and Output as Real-Time Feedback

A simple, noninvasive gauge: aim for pale straw–colored urine most of the day. Very dark urine hints at concentrated output and likely under-hydration; perfectly clear for long stretches can suggest over-drinking. Supplements (B-vitamins), some foods, and certain medications can tint urine, so interpret color alongside thirst, energy, and context (heat, exercise). Health services commonly teach the “pale yellow” target because it’s practical and correlates with more dilute urine.

5.1 Mini-checklist

- Pale straw to light yellow most of the day = on track.

- Dark apple-juice color = drink and reassess patterns.

- Crystal clear, all day, plus frequent bathroom trips = consider cutting back a bit (especially if you’re not hot/active).

5.2 When to be cautious

Persistent dark urine with dizziness, confusion, or very low output—especially during heat/illness—warrants prompt medical advice.

Bottom line: Color is a quick compass—simple, free, and effective when used with context.

6. Adjust for Pregnancy and Breastfeeding

Hydration needs increase to support blood volume expansion, amniotic fluid, and (later) milk production. The U.S. National Academies set ~3.0 L/day total water for pregnancy and ~3.8 L/day for lactation (of which a large portion is beverages). EFSA’s guidance for Europe is lower but directionally similar: ~2.3 L/day in pregnancy and ~2.7 L/day in lactation. In practice, most people meet these by adding ~1–3 cups of fluids beyond their usual baseline and eating water-rich foods. Nausea, vomiting, or hot weather raise needs further; check urine color and keep a bottle handy at all times.

6.1 Numbers & guardrails

- Pregnancy: target ~3.0 L/day total water (U.S. NAM).

- Breastfeeding: target ~3.8 L/day total water (U.S. NAM).

- Europe: +300 mL (pregnancy) and +700 mL (lactation) over adult female AIs.

6.2 Practical tips

- Pair a full glass of water with every feed or pumping session.

- Use a 750–1,000 mL bottle and aim to finish it 2–3 times daily.

- If vomiting, consider oral rehydration solution (ORS) sips and call your clinician if you can’t keep fluids down.

Bottom line: Plan extra fluids proactively—the body’s demands increase before your thirst catches up.

7. Hydrate Smart During Illness (Fever, Vomiting, Diarrhea)

Illness changes fluid math. Fever increases insensible losses; vomiting/diarrhea cause both fluid and electrolyte loss. For mild to moderate dehydration, WHO/UNICEF reduced-osmolarity ORS is the gold standard: ~75 mmol/L sodium, 75 mmol/L glucose, total osmolarity ~245 mOsm/L. Small, frequent sips work better than chugging; aim to replace ongoing losses and keep urine light. Seek urgent care if there’s persistent vomiting, lethargy, blood in stool, or signs of severe dehydration.

7.1 How to do it

- Start with 5–15 mL sips every few minutes; double gradually if tolerated.

- Use commercial ORS packets as directed; homemade mixes risk dangerous sodium/glucose errors.

- Continue normal diet as tolerated (rice, bananas, soups) and avoid sugary sodas/juices for rehydration—they may worsen diarrhea.

7.2 Mini-case

After a GI bug with two loose stools/hour, you sip ORS steadily over 3–4 hours and switch to water + salty soup as symptoms ease. If output worsens or you can’t keep fluids down for >6–8 hours, seek care—especially for infants, older adults, or anyone with chronic disease.

Bottom line: During illness, switch from “hydrate generally” to ORS with precision.

8. Balance Fluids and Electrolytes—And Avoid Overhydration

More isn’t always better. Exercise-associated hyponatremia (EAH) happens when water intake outpaces sodium/water loss so much that blood sodium drops. Updated travel and heat guidance recommends drinking to relieve thirst, not forcing fluid, and taking supplemental sodium during many-hour efforts or heat exposures. “Never gain weight” across long events is a simple safety rule. In routine life, hyponatremia is rare—but in marathons, hot worksites, or military training, it’s a known risk.

8.1 Numbers & guardrails

- Do not exceed ~1.5 quarts (~1.4 L) per hour of fluid intake.

- For very prolonged efforts, include sodium from foods/appropriate drinks; many retail sports drinks are too low in sodium for extreme durations.

8.2 Mini-checklist

- Monitor body mass across long sessions; weight gain = overdrinking.

- Cramps, nausea, confusion, or headache with high fluid intake? Consider hyponatremia; seek medical help.

Bottom line: Hydration is fluids + electrolytes—balanced to thirst and losses.

9. Count All Fluids (Coffee/Tea Included), But Be Smart About Alcohol and Sugar

Yes, coffee and tea “count.” The National Academies note that caffeinated beverages contribute to daily total water intake similarly to non-caffeinated drinks for habitual users; the mild diuretic effect is transient at typical intakes. Alcohol is different: it suppresses anti-diuretic hormone and increases urine output, so go 1:1 with water and avoid binge drinking, especially in heat. For everyday hydration, prioritize plain water, sparkling water, or unsweetened tea; save sugary drinks for treats.

9.1 Practical swaps

- Morning coffee? Great—add a glass of water alongside.

- Craving fizz? Choose unsweetened seltzer with a splash of citrus.

- Heat wave happy hour? Skip hard seltzers; choose mocktails or alternate every alcoholic drink with water.

9.2 Quick cautions

- Energy drinks: high caffeine + sugar can complicate hydration and heart rate; not recommended for kids/teens.

Bottom line: Most non-alcoholic drinks help; alcohol often hurts; sugar adds empty calories.

10. Convert Units, Pick a Bottle, and Plan Your Day

Confused by liters, cups, and ounces? Quick conversions help habits stick. 1 liter ≈ 4.23 U.S. cups (8 fl oz each); 250 mL ≈ 1 cup is close enough for meal planning. Choose a bottle that matches your routine: 500 mL for pockets, 750–1,000 mL for desks or gyms. Build anchors—one glass on waking, one with each meal, one mid-morning and mid-afternoon, and extra around workouts or heat.

10.1 Mini-checklist

- Keep water visible (desk, bag, car).

- Pair drinking with habits (meals, meetings, alarms).

- Use a bottle with graduations; aim to finish 2–4 fills depending on your target.

10.2 Example day (office worker, temperate climate)

- Wake: 300 mL; Breakfast: 300 mL; Mid-AM: 300 mL; Lunch: 400 mL; Mid-PM: 300 mL; Dinner: 400 mL; Evening: 300 mL → ~2.3 L beverages + water-rich foods pushes total near many women’s AIs (adjust as needed).

Bottom line: Make hydration easy: convert once, plan lightly, and let your bottle do the reminding.

11. Tailor for Kids, Older Adults, Altitude, and Air Travel

Kids need structured access to drinks, especially during sports and heat; use age-based cup guides (Rule 2) and pack water-rich snacks (melon, oranges, cucumbers). Older adults may need scheduled fluids and caregiver prompts—thirst cues can be unreliable and kidneys conserve water less effectively with age. For altitude, focus on gradual ascent, adequate (not excessive) hydration, and avoiding alcohol in the first 48 hours. Air travel is drying; bring a bottle, sip regularly, and walk the aisle when possible.

11.1 Region & travel notes

- Altitude travel (CDC Yellow Book, 2025): ascend gradually; avoid alcohol initially; maintain usual caffeine if you’re a regular user (to avoid withdrawal headaches). Hydrate sensibly—overdrinking offers no benefit and can be harmful.

- Care settings: dehydration is common in long-term care; proactive hydration programs reduce falls and UTIs.

11.2 Quick planner

- Kids’ sports: water first; for >60–90 minutes in heat, consider a salted snack or diluted sports drink.

- Older adults: small, frequent cups; favorite mug near the chair; fluids with meds/meals.

- Flights: refill after security; aim for a cup every hour you’re awake.

Bottom line: Life stage and location matter—customize your plan and set reminders where needed.

FAQs

1) What’s the difference between “total water” and “fluids”?

Total water includes moisture from foods and all beverages; fluids usually refers to beverages only. U.S. AIs (3.7 L men/2.7 L women) are total water, with about 20% from foods on average. That means many adults reach their goals with ~2.2–3.0 L of beverages plus water-rich foods.

2) Is the “8×8 rule” (eight 8-oz cups) correct?

It’s a simple starting point for some people, but it’s not evidence-based for everyone. Your needs vary by body size, climate, and activity, and authoritative AIs are higher for many adults. Use Rules 1–5 to tailor a number you can sustain.

3) Do coffee and tea dehydrate you?

Not in moderate amounts for habitual drinkers. The National Academies conclude caffeinated beverages contribute to hydration similarly to non-caffeinated beverages. Very high caffeine or unfamiliar intake can increase urination briefly, but typical coffee/tea count toward your daily total.

4) How can I estimate my personal exercise hydration?

Measure sweat rate: weigh before and after a typical workout (same clothes, towel off), and track drinks. Replace losses so body mass stays within ~2% of starting weight; most people fall around 0.4–0.8 L/h during endurance work. Post-exercise, rehydrate with ~1.5 L per kg lost.

5) What are early signs I’m under-hydrated?

Thirst, darker urine, fatigue, headache, and constipation are common signals. In heat, look for cramps, dizziness, or confusion; during illness, watch for low urine output and dry mouth. Pale yellow urine is a good day-to-day target.

6) Can I drink too much water?

Yes—especially during long events or heat if you’re drinking far more than you’re sweating. Hyponatremia risk rises if you gain weight during activity or drink >~1.4 L/h for hours. Drink to relieve thirst, include sodium for prolonged efforts, and seek help if you feel nauseated, confused, or have a pounding headache.

7) Should kids use sports drinks?

For most practices/games under ~60–90 minutes, water is best. In prolonged heat or tournaments with back-to-back play, a salted snack or an appropriately formulated drink can help—just watch sugar. Use age-based beverage targets (Rule 2) and pack water-rich snacks.

8) What if I have kidney stones?

High fluid intake is a cornerstone of prevention. Guidelines often aim for urine output ≥2–2.5 L/day, which typically means drinking enough to exceed that output (since you’ll lose some water through sweat/breath). Work with your urologist for personalized targets.

9) How does altitude affect hydration?

At altitude, breathing is faster and air is drier, so you’ll lose more water. Focus on gradual ascent, avoid alcohol for the first 48 hours, and hydrate adequately (not excessively). If you’re a regular caffeine user, keeping your normal intake can prevent withdrawal headaches.

10) Do water-rich foods count?

Absolutely. Fruits and vegetables (e.g., cucumbers, melons, leafy greens), soups, and yogurt contribute meaningfully—on average about 20% of daily total water. This is one reason strict “cups of water” targets can be misleading.

11) I rarely feel thirsty—am I safe to drink less?

Thirst is useful but imperfect. In older adults and some settings (care homes, cognitive impairment), thirst cues are blunted; relying on them can under-shoot needs. Use scheduled drinks, pair fluids with meals/meds, and check urine color.

12) What should I drink when I’m sick with diarrhea?

Use WHO/UNICEF reduced-osmolarity ORS—it has the right balance of sodium and glucose for absorption. Take small, frequent sips and seek care for severe or persistent symptoms, infants, older adults, or anyone with chronic conditions.

Conclusion

Hydration isn’t a single number—it’s a system you can learn and adapt. Start with authoritative baselines (Rule 1), then tune for your size, age, climate, and activity (Rules 2–4). Use real-time feedback like urine color and body mass change to stay on track (Rule 5). Add extra flu ids for pregnancy/lactation (Rule 6) and illness (Rule 7); keep electrolytes in step with fluids to avoid both dehydration and overhydration (Rule 8). Count all beverages—coffee and tea included—while limiting alcohol and sugary drinks (Rule 9). Make the math easy with simple conversions and daily anchors (Rule 10), and tailor for kids, older adults, altitude, and travel (Rule 11). With this playbook, you’ll cover the science and the day-to-day choices that make hydration effortless.

CTA: Fill your bottle now and try the pale-yellow test today—then adjust using one rule from this guide every week.

References

- Dietary Reference Intakes for Water, Potassium, Sodium, Chloride, and Sulfate (Chapter 4: Water) — National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2005). https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/10925/chapter/6

- How Much Water Do You Need? — Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, The Nutrition Source (Updated Feb 26, 2025). https://nutritionsource.hsph.harvard.edu/water/

- Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for Water — European Food Safety Authority (EFSA Journal, 2010). https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/1459

- Heat Stress—Recommendations to Prevent Heat-Related Illness — CDC/NIOSH/OSHA (web guidance; page includes “do not drink more than 1.5 quarts per hour”). https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/heatstress/heatrelillness.html

- Heat and Cold Illness in Travelers — CDC Yellow Book (Updated Apr 23, 2025). https://www.cdc.gov/yellow-book/hcp/environmental-hazards-risks/heat-and-cold-illness-in-travelers.html

- Exercise and Fluid Replacement (Position Stand) — American College of Sports Medicine (2007). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17632469/

- Hydration Guidelines (Handout) — National Athletic Trainers’ Association (NATA) (2016). https://www.nata.org/sites/default/files/hydration-guidelines_handout.pdf

- Fluid Replacement in Sports (DGE Working Group Position) — German Journal of Sports Medicine (2020). https://www.germanjournalsportsmedicine.com/archive/archive-2020/issue-7-8-9/fluid-replacement-in-sports-position-of-the-working-group-sports-nutrition-of-the-german-nutrition-society-dge/

- Medical Management of Kidney Stones: AUA Guideline — American Urological Association (2014). https://www.auajournals.org/doi/10.1016/j.juro.2014.05.005

- Domestic Water Quantity, Service Level and Health (summary of NAM AIs and food contribution) — World Health Organization (2020). https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/338044/9789240015241-eng.pdf

- High-Altitude Travel and Altitude Illness — CDC Yellow Book (Updated Apr 23, 2025). https://www.cdc.gov/yellow-book/hcp/environmental-hazards-risks/high-altitude-travel-and-altitude-illness.html

- WHO/UNICEF Reduced-Osmolarity Oral Rehydration Salts (ORS) — Product & Composition Guidance — USAID/UNICEF summary (2018) + WHO report (2001). https://www.ghsupplychain.org/sites/default/files/2019-02/MNCH%20Commodities-OralRehydration.pdf ; https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/67322/WHO_FCH_CAH_01.22.pdf