Failure can be uncomfortable, but it is also one of the most reliable teachers you’ll ever have. This guide shows you how to convert setbacks into structural advantages—at work, in school, in entrepreneurship, and in personal goals—without the shame or waste that usually comes with them. You’ll learn clear frameworks, practical templates, and tested routines for turning mistakes into momentum. In short: embracing failure as a learning tool means deliberately converting errors and near-misses into structured feedback and action that improves future performance. Done well, it makes you faster, calmer, and more effective.

Quick-start (the 9 steps): (1) Define failure and agree a learning contract; (2) Create psychological safety so people speak up; (3) Run pre-mortems to surface risks early; (4) Test with small, reversible bets (PDSA); (5) Instrument feedback and learning KPIs; (6) Hold blameless postmortems and assign actions; (7) Use deliberate practice to build skill; (8) Reframe emotions and recover with intention; (9) Capture, share, and revisit lessons so knowledge compounds.

Brief note: This article shares general frameworks for learning and performance. It isn’t medical, legal, or financial advice.

1. Define “failure” and set a learning contract

The first step is to remove ambiguity: define what failure means in your context and agree—in advance—that the purpose of finding it is learning, not punishment. Without a shared definition, teams and individuals either hide mistakes or argue about labels (“bug,” “incident,” “oops”) instead of solving them. A simple learning contract makes the process explicit: we run experiments, we expect some to miss, and we commit to extracting value from every miss. This framing transforms “failure” from a character judgment into an information event. It also lets you pick thresholds (impact, cost, safety) that trigger deeper analysis versus quick fixes. Establishing these ground rules up front accelerates decisions later, because everyone knows what qualifies as a meaningful signal and what process follows from it.

1.1 Why it matters

- Clarity reduces defensiveness and speeds reporting.

- Shared definitions prevent “success theatre”—cosmetic wins that hide real problems.

- Pre-committing to a process keeps emotions from hijacking sensemaking when something breaks.

1.2 How to do it

- Write a glossary: Define “experiment,” “error,” “incident,” “near-miss,” and “failure.”

- Set guardrails: Specify impact thresholds (e.g., “If customer downtime > 20 minutes, run a postmortem within 72 hours”).

- Adopt a learning contract: One page that states: “We assume good intent; we value candor; we focus on systems; we fix process, not people.”

- Choose templates now: Decide which pre-mortem, postmortem, and PDSA forms you’ll use, and where they live.

Synthesis: When everyone knows what “failure” means and which playbook it triggers, the conversation shifts from blame to learning, and from confusion to cadence.

2. Build psychological safety so people speak up sooner

Embracing failure is impossible if people fear the social cost of reporting problems. Psychological safety—shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk—predicts whether issues surface early enough to fix. Teams with high safety file bugs sooner, ask naive questions, and escalate ambiguous data before crises harden. Creating that climate is not mushy; it’s managerial technique. Leaders model curiosity, invite dissent, and thank people for raising concerns. They replace “Who messed up?” with “What did our system make easy to get wrong?” Safety doesn’t dilute accountability; it makes it precise by locating causes in processes, not personalities.

2.1 What leaders can do this week

- Frame the work as learning: “We’re inventing under uncertainty; we need everyone’s eyes.”

- Model fallibility: Admit a recent mistake and one thing you changed.

- Reward candor publicly: Celebrate a teammate who raised an uncomfortable risk early.

- Use neutral language: Say “the code path caused X,” not “you caused X.”

- Close the loop: Report back on how feedback changed the plan.

2.2 Common mistakes

- Performative agreement: Teams nod in meetings and go silent afterwards—measure safety with short pulses, not vibes.

- Anonymous-only channels: Useful as a start, but aim for open dialogue supported by norms.

- Punitive surprises: Hidden consequences destroy safety; if consequences exist, state them clearly and consistently.

Synthesis: You can’t learn from failures nobody shares. Build safety deliberately, and you’ll see issues sooner, cheaper, and with more options intact.

3. Run pre-mortems to surface risks before they bite

A pre-mortem is a fast, structured exercise where you imagine the project failed spectacularly and generate the most plausible reasons why. Unlike generic risk logs, the pre-mortem invites vivid storytelling and dissent; it licenses people to say the quiet part out loud. This “assume failure first” posture uncovers fragilities—single points of failure, hidden dependencies, unrealistic timelines—that status meetings gloss over. By converting these into mitigations and “tripwires,” you create early-warning signals and fallback plans before you spend serious time or money.

3.1 How to run a 45-minute pre-mortem

- Prime: “It’s six months from now and the project failed. What happened?”

- Silent write (5–7 min): Each person lists 5–10 concrete causes.

- Round-robin share: Capture on a board without debate.

- Cluster & vote: Group similar risks; dot-vote top 5–7.

- Convert to mitigations: For each top risk, define a prevention step, a detection signal, and a contingency plan.

- Assign owners & dates.

3.2 Mini-case

A product team planned a launch reliant on a partner API. The pre-mortem surfaced “partner rate limits” as a failure cause. They added a throttle, a retry/backoff strategy, and a sandbox test. On launch day, rate limits hit—but the system degraded gracefully and shipped on time.

Synthesis: Pre-mortems trade cheap imagination for expensive surprises. They turn “we hope this works” into “we’ll know quickly if it doesn’t—and what we’ll do next.”

4. Test with small, reversible bets (PDSA beats all-or-nothing)

Big-bang changes magnify the cost of mistakes; small, reversible tests shrink it and multiply your learning rate. The Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle is a simple way to structure these small bets: plan the change and expected signal, do a limited test, study the actual outcomes, act by adopting, adapting, or abandoning. In software, this looks like feature flags and staged rollouts; in healthcare, it might be piloting a new triage question for one shift; in personal goals, it’s a 2-week micro-habit trial. By keeping the batch size tiny and the feedback tight, you de-risk experimentation and normalize “fail-fast, fix-fast.”

4.1 Numbers & guardrails

- Scope: Limit initial exposure to <10% of users/patients/time.

- Timebox: 1–2 weeks for first cycle; longer cycles spread learning too thin.

- Decision rule: Pre-declare “If metric X improves ≥5% without Y worsening, proceed to 25% rollout.”

- Reversibility: Ensure you can roll back within minutes (software) or a shift (operations).

4.2 Mini-checklist

- Do we know the primary signal we’re testing?

- What’s the harm we’re watching for?

- How quickly can we undo this?

- What is the next PDSA if this one is inconclusive?

Synthesis: Small bets make failure tolerable and informative. With PDSA, you build a portfolio of experiments that steadily tilts outcomes in your favor.

5. Instrument feedback and define “learning KPIs”

You can’t learn from failure without measures that detect it and indicators that prove you’ve learned. Most teams track outcome metrics (revenue, NPS, test scores) but neglect process and learning metrics. Add signals that show whether your experiments are generating insight and capability: cycle time from incident to insight, % of experiments with a clear decision rule, number of “tripwires” that triggered early detection, time-to-roll-back, and action-item closure rate after postmortems. For individuals, track “focused practice hours,” “feedback latency,” and “retros completed per week.” These learning KPIs keep attention on the health of your improvement engine, not just end results.

5.1 What to measure (examples)

- Detection speed: Time from anomaly to acknowledgement.

- Containment speed: Time from acknowledgement to mitigation.

- Insight rate: % of incidents generating at least one validated hypothesis.

- Action closure: % of postmortem actions completed within 30 days.

- Practice volume: Hours of deliberate practice per week (skill-building contexts).

- Feedback latency: Hours from practice to feedback received.

5.2 Tools & examples

- Dashboards: Lightweight boards (Notion, Airtable, Sheets) with weekly snapshots.

- Runbooks: Living documents that link incidents to actions and owners.

- Personal tracker: A one-page “practice ledger” noting reps, feedback, and adjustments.

Synthesis: Outcomes lag. Learning KPIs lead. Track them and you’ll spot problems—and progress—while there’s still time to steer.

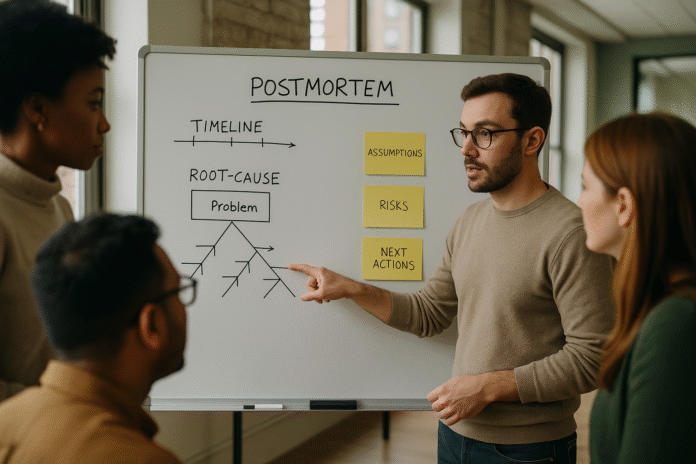

6. Hold blameless postmortems that change behavior

A blameless postmortem is a structured, written account of what happened, why it made sense at the time, and what you’ll change so it’s less likely or less harmful next time. The “blameless” part is not leniency; it’s accuracy. People act within systems—tools, alerts, incentives, information—so the fix lives there too. Good postmortems include a timeline, technical and human factors, clear actions with owners/dates, and follow-ups to verify the fix. Great ones also include “what worked,” so you preserve good adaptations alongside the bugs. The goal is not to archive a story; it’s to alter future behavior and reduce repeat pain.

6.1 Anatomy of a strong postmortem

- Trigger & scope: Why we’re writing; what systems/customers were affected.

- Timeline: Facts only; minute-by-minute is ideal for incidents.

- Causal analysis: Multiple contributing factors; avoid single-cause fallacies.

- Counterfactuals: “What signal would have changed our judgment earlier?”

- Actions: Specific, testable, prioritized, each with an owner and date.

- Verification plan: How we’ll know the fix actually works (and when we’ll check).

6.2 Meeting tips

- Ban “who” questions until system factors are mapped.

- Capture decision-making context (alerts, dashboards, norms).

- End with two lists: “Fixes we’ll implement” and “Assumptions we’ll test.”

Synthesis: Postmortems are the hinge between failure and improvement. Make them blameless, specific, and verifiable—or don’t bother holding them.

7. Use deliberate practice to convert insight into skill

Insight without skill stays theoretical; deliberate practice turns it into performance. After a failure, identify the sub-skill that broke (e.g., pacing a race, negotiating scope, triaging alerts) and design drills that target it just beyond your current ability with frequent, expert feedback. This formula—not just time on task—explains why some people improve quickly after setbacks while others repeat the same errors. Combine failure data (what went wrong) with focused reps (what we’ll do differently) and you create a tight loop from error to mastery.

7.1 How to design a drill

- Define the bottleneck: Name the exact behavior to change (“first response time to pages > 10 min”).

- Set a stretch target: Clear and specific (“≤ 3 minutes for 4 consecutive weeks”).

- Constrain variables: Practice in a controlled environment (simulator, sandbox, role-play).

- Shorten feedback: Use timers, checklists, and expert critiques within minutes, not days.

- Track reps: Log attempts, outcomes, and adjustments.

7.2 Example: Negotiation after a failed project estimate

- Failure signal: Chronic underestimation led to missed deadlines.

- Drill: Weekly 30-minute role-plays on pushing back against scope creep; immediate feedback on phrasing and pauses.

- Metric: % of proposals that include trade-offs (time/scope/budget).

- Result: Within 6 weeks, proposals included trade-offs by default; deadlines stabilized.

Synthesis: Don’t just vow to “be better next time.” Decide which micro-skill will make the next failure less likely, then practice that skill deliberately.

8. Reframe emotions and recover with intention

Emotions after failure are data, not destiny. Cognitive reappraisal—reinterpreting an event to change its emotional impact—reduces rumination and speeds recovery. Instead of “I’m terrible at this,” reframe to “This exposure clarified the next skill to practice.” Pair reappraisal with a recovery routine: sleep, movement, social support, and a time-boxed reflection. In teams, leaders can normalize this cycle by acknowledging the sting, then guiding attention to learning actions. The aim isn’t to suppress feeling; it’s to prevent feelings from locking in maladaptive conclusions that slow future action.

8.1 A 20-minute recovery protocol

- Five-minute body reset: Walk, stretch, breathe 4-7-8 for three rounds.

- Ten-minute write-through: What happened? What did I control? What will I try next?

- Five-minute connection: Share one learning with a peer or mentor; ask for one suggestion.

8.2 Reappraisal scripts (use verbatim or adapt)

- “This result narrows the search space. That’s valuable.”

- “I can’t change the past hour, but I control the next rep.”

- “Our process produced exactly the output it was designed for—it’s the design we’ll change.”

Synthesis: Feel the loss, then move. Reappraisal plus a simple recovery ritual turns emotional energy into the fuel for your next iteration.

9. Capture, share, and revisit lessons so knowledge compounds

Learning compounds only if you capture it, share it, and revisit it on a schedule. Otherwise, the same failures recur as institutional amnesia. Build a lightweight “failure-to-learning” workflow: a central place for pre-mortems, postmortems, decisions, and playbooks; a weekly or bi-weekly review to surface patterns; and a monthly “learning release” that highlights what changed. For individuals, keep a one-page “Lessons Log” with date, context, what failed, what you tried, what you’ll try next, and a status check 30 days later. The goal is searchable memory and scheduled reflection—not a museum of PDFs.

9.1 Minimum viable knowledge system

- Single source: One folder or workspace for experiments and incident reviews.

- Tags that matter: Tag by system, root cause, and impacted metric.

- Review cadence: 30-minute weekly review; 60-minute monthly synthesis.

- Distribution: A short internal newsletter—“Here’s what we learned and changed.”

9.2 What “good” looks like in 90 days

- Repeated issues decline; detection gets faster.

- Reviews talk about systems and signals, not personalities.

- New hires ramp faster because history is searchable.

- Stakeholders see consistent learning actions attached to metrics.

Synthesis: Memory makes learning exponential. Capture lessons, schedule reviews, and your organization (or personal practice) will get smarter every month.

FAQs

1) What does “embracing failure as a learning tool” actually mean?

It means treating failures as information events that trigger a pre-agreed improvement process—pre-mortems, small tests, postmortems, and deliberate practice—rather than as personal verdicts. The goal isn’t to excuse mistakes; it’s to extract maximum learning per unit of pain, so your next decision is better and your systems are safer.

2) Isn’t “blameless” too soft—how do we keep accountability?

Blameless isn’t blame-free; it’s system-first. You still assign owners for actions with dates, verify fixes, and track closure. But you analyze how tools, alerts, incentives, or training made a mistake likely, and you fix those levers. Accountability becomes measurable—did we change the system and did the metrics improve—rather than emotional finger-pointing.

3) How often should we run postmortems?

Tie them to thresholds you define up front (e.g., customer-visible downtime beyond X minutes, safety events, significant cost overruns). Minor, well-contained issues may only warrant a brief note. The key is consistency: when a trigger fires, the process runs within a set time window, and actions are tracked to completion.

4) What’s the difference between a pre-mortem and a risk register?

A pre-mortem assumes failure has already occurred and invites everyone to vividly explain why. That framing surfaces specific, socially awkward risks a generic register misses. You still record outcomes in a register, but the pre-mortem is the engine that populates it with concrete, testable risks and early-warning tripwires.

5) How do we measure if we’re actually learning?

Add learning KPIs alongside outcomes: time to detect and contain issues, percentage of experiments with a pre-declared decision rule, postmortem action closure rate, and feedback latency for practice. If those numbers improve over weeks, your learning engine is healthy—even before end results move.

6) Won’t small tests slow us down?

Counterintuitively, small, reversible tests speed you up by preventing big rework. You still move to larger rollouts as evidence accumulates, but the early stakes are low, so you can try more ideas. That portfolio approach spreads risk and increases the probability that at least one path works well.

7) How do we handle the emotions after a public mistake?

Name the emotion, normalize it, and then channel it. Use a brief recovery protocol (movement, write-through, connection) and cognitive reappraisal to avoid rumination. Leaders should acknowledge the sting, thank people for surfacing facts, and pivot quickly to the next concrete action tied to the learning plan.

8) Can these ideas work outside tech or startups?

Yes. Healthcare uses PDSA cycles; aviation and energy rely on incident reviews; classrooms use error-based learning to improve recall. The specifics of thresholds, templates, and safety rules will differ by domain, but the underlying logic—small bets, fast feedback, system fixes—travels well.

9) How do I start if my culture currently punishes mistakes?

Begin with a small sphere you control: a team, a project, or your own practice. Establish clear definitions and a learning contract. Run a pre-mortem, pilot a tiny change with a decision rule, and hold a blameless review. Share early wins—faster detection, fewer repeats—to build permission for a wider rollout.

10) What if leadership wants names attached to errors?

Offer a compromise: names attach to actions (owners, due dates), while the analysis focuses on system conditions. Show how system fixes reduce recurrence, saving money and reputation. Over time, reliable results build trust in a blameless yet rigorous approach that still delivers accountability.

Conclusion

Failure doesn’t have to be final or fatal; it can be a feature of a smart system. When you define failure upfront, invite dissent with pre-mortems, test with small PDSA cycles, instrument feedback, and hold blameless postmortems, you reduce the cost of mistakes and increase the value of each one. Pair that with deliberate practice and intentional recovery, and your skills grow faster—because every miss refines the next rep. Finally, by capturing and revisiting lessons, you compound knowledge so your organization (or personal practice) becomes harder to surprise and easier to steer. Start with one step this week—perhaps a 45-minute pre-mortem on your next project or a single PDSA test on a nagging process—and let the momentum build.

Call to action: Pick one current project, schedule a 30-minute pre-mortem, and commit to one small PDSA test within the next seven days.

References

- Edmondson, A. “Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams.” Administrative Science Quarterly, 1999. https://web.mit.edu/curhan/www/docs/Articles/15341_Readings/Group_Performance/Edmondson%20Psychological%20safety.pdf

- Klein, G. “Performing a Project Premortem.” Harvard Business Review, September 2007. https://hbr.org/2007/09/performing-a-project-premortem

- “Blameless Postmortem for System Resilience.” Site Reliability Engineering (Google SRE Book), n.d. https://sre.google/sre-book/postmortem-culture/

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. “Building a Practically Useful Theory of Goal Setting and Task Motivation: A 35-Year Odyssey.” American Psychologist, 2002. (PDF via Stanford Medicine) https://med.stanford.edu/content/dam/sm/s-spire/documents/PD.locke-and-latham-retrospective_Paper.pdf

- Huelser, B. J., & Metcalfe, J. “Making Related Errors Facilitates Learning, but Learners Do Not Always Know It.” Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 2012. (PDF via Columbia University) https://www.columbia.edu/cu/psychology/metcalfe/PDFs/Huelser_Metcalfe_2012.pdf

- Gross, J. J. “Emotion Regulation: Affective, Cognitive, and Social Consequences.” Psychophysiology/Review Articles, 2002. (PubMed entry) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12212647/

- “Understand Team Effectiveness (Project Aristotle).” re:Work with Google, n.d. https://rework.withgoogle.com/intl/en/guides/understanding-team-effectiveness

- “Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) Worksheet.” Institute for Healthcare Improvement, n.d. https://www.ihi.org/library/tools/plan-do-study-act-pdsa-worksheet

- “Postmortem Practices for Incident Management.” Google SRE Workbook, n.d. https://sre.google/workbook/postmortem-culture/

- “How to Run a Blameless Postmortem.” Atlassian Incident Management Guide, n.d. https://www.atlassian.com/incident-management/postmortem/blameless